A person raises their hand to their head in the foreground; the person in the background is out of focus.

A few months ago, I broke my phone screen. (Pro tip: Don’t leave an uncased phone on your bed after pleasuring yourself before bedtime.)

I took it to a repair shop just a block away from where I was working to get it fixed.

The guy behind the counter clearly took major interest in me from the moment I walked in.

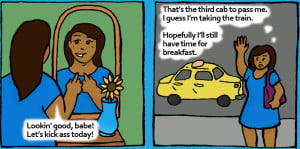

I didn’t make much of it; I get it, I have a magnetic personality. Also, because I, like so many other women, am accustomed to catcalling, having my boundaries violated, and my “no” disrespected, I’m generally well-scripted in how to get through these moments.

I indulged his many personal questions about my life until he started asking about whether I was single – at which point, I told him firmly that I was most definitely not interested.

He asked me for my phone number for the transaction, so I gave the one associated with my broken phone and left, expecting to just come back tomorrow afternoon to drop off my phone when the part was scheduled to arrive.

Then it got weird.

He chased me down the sidewalk to ask if he could call me – first in relation to the phone part (I said no), then just personally, since he wouldn’t be in the store tomorrow (I said no again).

I laughed it off as an example of a very persistent dude, because I often laugh in situations where I am masking other emotions like fear and discomfort. And I posted the story on Facebook framing it as a “funny” thing that happened to occur.

But a day after my phone was repaired, he sent me messages on a messaging app that he could only have found me on through my phone number. Even though this is a breach of privacy, I was only thinking, The gall of this guy!

I posted screenshots of these messages on Facebook as a follow-up to my “phone repair saga,” proclaiming my shock and offense.

Believe it or not, I only realized how terrifying and inappropriate this was after outrage from some of my friends: “How are you supposed to trust that someone who uses information obtained during a business transaction won’t use your credit card information for personal gain?”

I did end up reporting him (and ultimately, he was fired) but not without my having some qualms about it first.

Here are four reasons I had mixed feelings about reporting him, but still think that what I did was reasonable.

1. I’ve Internalized the Idea That Persistence Is ‘Romantic’

The truth is it’s actually disrespectful for suitors to continue pursuing me when I’ve repeatedly said “no.”

It’s a demonstration that they don’t care about consent and don’t see me as a person worthy of treating with dignity.

When I told my mom what happened, she said, “That’s kind of mean – he just liked you!” And that’s the same type of sentiment that we’re exposed to in heterosexual (and often heteronormative) romantic narratives.

For example, in The Notebook, Noah threatens to hurt himself by falling off a Ferris wheel if Allie won’t date him. This type of coercive behavior is actually threatening, emotionally manipulative, and terrifying – but we’re asked to see it as a romantic grand gesture of love instead.

So, honestly, a part of me still does think this compulsive and unhealthy erraticism is romantic instead of boundary-violating.

A lot of movies and stories perpetuate the idea that no doesn’t really mean no and that men simply have to be persistent to “get the girl.”

This is a concept that not only goes back ages, but is portrayed as innocent and appears even in children’s cartoon characters like Pepé Le Pew, a skunk that’s always chasing the affection of a female black cat, even after repeated rejection.

Believing that this type of unwanted persistence is indicative of love invalidates the importance of consent and perpetuates rape culture.

This type of messaging tells the pursuer (often men) they don’t have to take “no” seriously, and tells women that they shouldn’t be upfront and honest about their desires because social scripts dictate one should play hard-to-get or be coy.

This same social script enforces the assumption that men enjoy the pursuit or conquest more than the relationship. And why would we want a relationship to be considered a goal less rewarding than the process of getting into it?

But even if the guy at the phone repair shop “liked” me – and by “liked,” we really mean “found me physically attractive” – it doesn’t excuse his behavior.

I already told him I wasn’t interested, but instead of respecting my choice, he decided that he simply needed to spend more effort convincing me to give him a chance.

2. I Wondered If I Actually Found Him Attractive

Imagine if I did give him a chance. Suppose I was charmed. Suppose I did find his persistence romantic because of the many chick flicks I’ve watched.

It would mean that the entirety of our relationship would be predicated on his initial violation of my boundaries, sending the message that he doesn’t have to take my needs seriously when he can override me by being more persistent.

Rewarding persistence perpetuates dysfunctional social interactions. It sends the message that people can successfully use this approach to bully others into romantic relationships and that it’s okay t0 use it within relationships to get what they want.

It also suggests they can continue to further defy boundaries.

And that’s precisely why I reported him. The violation of one boundary immediately erodes any baseline level of trust and suggests that he could violate another.

What if he didn’t stop messaging me? What if he started sending emotionally coercive messages?

What if he found my home address via my billing information and decided to stop by? What if he visited my office, which was only steps from the shop?

He could use the same behaviors to emotionally manipulate me within a romantic relationship.

My safety had been compromised, and that’s not romantic at all – that’s terrifying.

3. Reporting Doesn’t Necessarily Lead to Learning

The manager of the phone repair store told me that they fired the guy who sent me those messages, but I don’t know if he was reprimanded. And if he was, how was he reprimanded?

I don’t know if he’s learned that what he did was wrong because he:

- Used information obtained during a business transaction for personal use

- Created a power dynamic that made the customer feel unsafe

- Violated my boundaries

I don’t know if he’ll have an opportunity to learn about healthy, respectful ways to express interest. What if, instead of learning to express his attraction in appropriate ways and situations, he only learned never to express his interest in women honestly?

What if he just internalizes a hatred of women because he ended up losing his job?

These questions I still have speak to our entire society’s use of misaligned incentives and reinforcements that emphasize punishment over reform, growth, and learning.

This is a product of our culture and society, which are not set up to treat or view people as multifaceted, complex beings whose interactions with society are based on an amalgamation of identities.

It’s easier instead to fit people into a single role that explains their entire personhood – like rapist, domestic abuser, ex-convict, feminist, terrorist.

We often use these labels to describe ourselves (and others) as a political act that minimizes or maximizes particular identities depending on whether the aim is to appear more humanized and relatable or more polarized to a particular audience.

This allows us to have absolute and unequivocal reactions when it comes to issues of sexual harassment and sexual violence.

We often desire maximum punishment focusing on the value of harm we place on the action of the aggressor, not restorative justice, because our system is set up to punish, not rehabilitate.

And in trying to protect and validate the impact on the harmed individual, we advocate for repercussions that demonstrate to us that society cares about the harmed individual.

For many women, we’re learning to finally even be assertive at all about enforcing our boundaries, and in this act of assertion, it’s easy to feel like we have to be unwavering advocates for penalizing transgressions against women’s equality.

But to be honest, human interactions are a lot more complicated simply because the repercussions don’t always make the best of a toxic situation.

I see the guy who hit on me as a human being who made a mistake and would benefit from learning why it was a mistake, a lesson that his being fired may or may not have taught him.

But I still felt that I should report his action, because at the very least, he would learn not to use a customer’s information for personal use.

Society benefits when people who believe their actions of persistence to be innocuous flirting stop doing it.

And yes, society would benefit even more if we all examined the detrimental impacts of our interactions with others, but it’s a start.

I’m hopeful that the more that people report these types of behaviors as inappropriate, the better workplaces will become at responding to these situations, and the more awareness there will be on healthy interactions with each other.

3. Reporting Has Disproportionate Consequences Depending on Class and More

This dilemma really bugs me because it’s something I can definitely get up on a soapbox and rant about for hours with no simple solutions in sight.

When I reported the guy who hit on me, I didn’t ask for him to be fired. I asked the manager to move him to a different location so he wouldn’t be close to where I worked. Because of this, I felt somewhat guilty when he lost his job.

Some may say I’m overextending sympathy, but I don’t think that mistakes and failures need to everlastingly ruin someone’s life – not that I think they will in this particular case, but sometimes society holds our actions against us in ways that limit our access to opportunity practically permanently.

I wonder if he found another job. I wonder if losing that source of income made his life more stressful.

As a person of color, too, I wonder if he was a first-generation immigrant. I also wonder if he would have been fired if he was the manager of the location – or if he was the only employee there who specialized in a particular type of phone repair.

People working in so-called low-skilled jobs or jobs where the worker has little power more often face consequences of their actions while those in positions of seniority, power, high visibility, and/or celebrity stature not only don’t face consequences, they can also deny reports against them and ruin the reputations of those who do report.

In fact, despite video evidence of misogyny and multiple sexual assault allegations, with enough wealth and power, one could run and become the next president of the United States without facing backlash for the way they talk about and treat women.

Wealthier and more powerful people who commit acts of violence against women (and other crimes) are more insulated and protected from seeing consequences of their actions than people of lower incomes who can’t afford the same level of defense or see the same type of outspoken social support in their favor.

This injustice is mirrored in our criminal justice system.

It is also reflected in whose lives matter more based on gender and race.

Belief in a woman’s report of sexual harassment and assault is dependent on their identities in relation to the identities of the perpetrator based on class, race, gender, occupation, and appearance.

Violence against trans women, sex workers, incarcerated women, Black women, indigenous women, Latinx women, and women of South Asian descent – many hold more than one of these identities, by the way – is routinely treated as mattering less than violence against white women as reflected by media portrayal and how the case is handled by law enforcement.

In fact, the 1915 US film The Birth of a Nation stoked racist populist politics and empowered the KKK by portraying Black men as sexual predators of white women, imagery that has persisted through today in mainstream depictions of Black male sexuality.

But as we saw in the Brock Turner case, the rape survivor’s life was treated as less important than Turner’s ruined future as a swim athlete and Stanford grad.

And we can talk at length on what psychological and systemic factors are at play in building these perceptions and prejudices about people’s lives – but they wouldn’t help us see justice for cases currently going through the system.

Not right now, at least.

But they do make me question: Should I report the immigrant Uber driver from a country that tends to have more explicitly sexist cultural norms when they’re expressing interest inappropriately? Do I say something about the server who has been paying unwanted attention to my table?

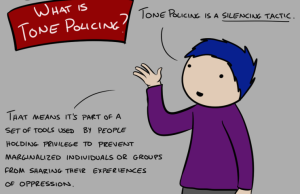

And the same power dynamics and perceptions of whose life matters more based on our identities makes reporting a high-risk action for those who are less privileged or more vulnerable to attacks on their character than the perpetrator.

In this case, it was relatively low-risk involved for me to report him. I was not threatened by the feeling that nothing would be done or by the feeling that there would be retribution.

It sucks that I was able to report this relatively low-harm scenario easily and attain due process when there are much more upsetting cases, cases where it’s not nearly as safe to seek some sort of justice.

And ultimately, I’m not sure I would report in every case, depending on the context, even though my ideals say I ought to choose this always-valid option.

Just because it’s unfair that people disproportionately face consequences based on their position in society doesn’t excuse their actions – and their actions are the main factor that influences our decision to report.

While implications that center the wellbeing of the perpetrator may align with our social justice values and demonstrate how systems of oppression play out on the lives of perpetrators, they don’t need to be considered or weighed against the damage they’ve caused to one’s own wellbeing in the decision to report.

At the end of the day, we can only attempt to seek limited justice while also trying to reform our models of justice as a whole.

***

It’s funny that when I tell this story to my girlfriends, they generally react with indignation and cathartic affirmations, because most of them have experienced street harassment.

“Good, I’m glad he was fired!”

When I tell it to my straight guy friends, a good number of them wince and feel sympathetic to the guy at the phone repair shop, because many of them haven’t been taught how to demonstrate interest and attraction in a respectful way and are navigating what they see as an increasingly complex social space.

“Damn, you got him fired!”

I don’t think these two reactions are mutually exclusive – nor are they split across the gender spectrum – and I definitely relate to both.

In fact, I think we need to recognize that it’s okay to feel conflicted about reporting people, because we are empathic beings capable of recognizing that other people deserve equal treatment for their humanity.

And I’m hoping that recognizing that these feelings are natural will make it easier for people to come to the decision to report.

We can’t change the effects of entire systems of oppression on the repercussions faced by reported offenders, and economic and racial issues or the issue of how to educate them on proper expressions of interest or proper treatments of other people don’t excuse their actions and the impact of their actions.

Reporting them for making you feel unsafe or threatened isn’t wrong. Nor is it wrong to believe that the person who caused these feelings should recognize what they did wrong and offer a sincere apology and/or retribution.

The one place where we have the greatest amount of personal agency is in controlling how we respond to how we are treated. Each of these actions contributes to a culture where women feel less safe in society, and each report is a message that we won’t condone it.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Jessica Xiao a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a self-proclaimed nerd and book hoarder who is guilty of tsundoku. Often inaccurately described as Canadian, she thinks of herself more as a Montrealer with US citizenship living in Washington, DC, after having obtained her BA & Sc. in Psychology and the dark art of Economics at McGill University. She is a grant writer for the Montreal-based international women’s economic development nonprofit Artistri Sud and the former assistant editor and writer at The Humanist. She believes in empathic action and bringing our whole selves to every aspect of our lives for transformational social change. She frequently quotes Dorothy Parker and writes bad poetry at stillsolvingforx.tumblr.com

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more