A parent and child holding mugs are talking to each other.

When I recall the sex ed I got growing up, I have to say, mine was solid enough, especially compared to a lot of what was (and currently is) on offer.

But when I recall the sex I actually had in high school, the best I can muster is meh.

There are a lot of reasons for that.

One of the big ones is that, despite living in a pretty liberal environment, something about the way sex was presented was still off.

I mean, I had parents who knew that I was on the Pill and let me sleep over at my boyfriend’s place. I went to a high school that, in addition to teaching pretty decent health classes, also had a condom machine in the bathroom.

And, I even lived only a bus ride away from a free, confidential teen sexual health clinic that provided everything from pap smears to birth control, abortion, and rape crisis counseling.

Yet the more I think about it, the more I feel like the “off” part had a lot to do with the messaging on pleasure. Or rather, the lack of a message about pleasure for anyone other than the cisgender, heterosexual boys who always seemed to get top billing in these conversations.

It’s not that I lived under a rock where the clitoral orgasm was some mythological thing.

But when it came to pleasure, classroom discussions about puberty equated periods (uncomfortable! messy!) with wet dreams (pleasurable! orgasmic!). Jokes about masturbation always focused on hapless single guys.

Indeed, even when two girls were dating, there were inevitably those boys who would try to co-opt the situation, opining about how hot they imagined the sex to be – as if they had a right to make this experience about their own desires.

In this environment we were constantly reminded that, while for a cis/hetero girl, sex could easily end in pregnancy, STIs, or heartbreak, the likely end result of sex for the cis/hetero guy was, well, an orgasm.

The takeaway was that the major benefit girls derive from having sex with boys was presented in relation to their social status and power, not actually pleasure or joy.

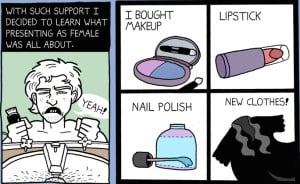

Combine that with the fact that almost all the messages assumed us to be cis/hetero kids and you get not only near-complete erasure of the entire LGBTQIA+ teen population, but an attack on their right to sexual health education and resources as well.

I teach at a high school now, have kids of my own, and know that in many ways our cultural understanding of sexuality has evolved since then.

But I also see that a lot remains the same. And there are consequences to this stagnation.

There are consequences for our understanding of gender roles and sexual expression. There are consequences for how we see gender identities and sexual orientations.

And there are consequences for rape culture – something that these views help perpetuate, since under this model, the sexual desires of cis/het boys are positioned as not only expected, but also as prioritized above everybody else’s.

Luckily, that doesn’t mean there isn’t hope for progress.

But since the majority of parents can’t depend on schools to impart an enlightened message about sexuality, and since it is pretty clear that we can’t look to mainstream media or schools to do so either, in many ways, it is up to us as parents to fill in the gaps and debunk the misconceptions.

Nevertheless, the idea of talking to your kids about sexual pleasure might seem daunting, uncomfortable, and maybe just plain wrong. And even if you are on-board conceptually, just what are these conversations supposed to look like?

I mean, are you really supposed to sit around with your 14 year old and tell them that whomever they are, they have a right to equal opportunity pleasure one day?

I’d say yes. But maybe not as a first step.

So before you get there, here are a few things you might want to consider.

1. Ask Yourself if How You Define ‘Sex’ is Limiting

When I teach about sexuality, I explain that I use the term sex to describe a huge range of ways that people can be intimate with someone else (or with themselves) that can include everything from kissing, to body rubbing, roleplay, and all manner of penetrative experiences.

But I am well aware that my definition is by no means a universal one. While the queer community has long had a more inclusive understanding of what it means to have sex, for a lot of cis/hetero people, the term “having sex” has generally been used to refer to penis-in-vagina intercourse (PIV), and has been seen as completed when the penis ejaculates.

This definition is complicated by old-fashioned views of virginity, something that in a lot of places is frequently prized in girls far more than in boys, and then by the resulting behaviors that occur.

For example, you may remember a bit of an uproar in the mid-2000s about teenage girls who were supposedly using anal sex to preserve their virginity while still providing a way for their boyfriends to get off.

Now, whether or not this was all that widespread, the idea that this was happening resonated with enough folks to keep it the regular media rotation for quite a while.

For the time being, this fear about wanton anal has died down, but the default assumption for a lot of people that PIV is the only “real” sex has not.

And that’s not just anecdotal. Multiple studies have found this to be the case, including, tellingly, one done by researchers at the University of Indiana’s Kinsey Institute which asked people what it meant to “have sex.”

What they discovered was that while nearly 95% of people in the study agreed on the definition of PIV sex, that’s where agreement ended.

Some of the most stand-out variations? Eleven percent of respondents did not consider it sex if the man did not come, and 18% percent of men over 65 did not consider PIV sex if a condom was used!

So, yeah…

As parents, it is probably a good idea to get a handle on what we think it means to have sex; and then, if our definitions are limited, consider expanding them to allow for a much richer sexual landscape before we try to help our kid navigate this terrain.

2. Consider Whether You Place More Importance on Certain People’s Pleasure Than on Others

The PIV view of sex and the assumption that this only happens between cis/hetero couples is yet another way we create a hierarchy of pleasure with one gender clearly coming out on top at the expense of others.

Combine this with a historical fear of women’s sexual pleasure – which stems in part from the idea that if women enjoy sex they will cheat and thus paternity can be called into question – and the policing of mainstream media representations of orgasm and masturbation and it is little wonder that the primacy cis/hetero men’s pleasure still looms so large for so many of us.

After all, we still live in an era when women receiving pleasure or orgasming on screen means a movie will likely see an R or NC-17 rating while male sexual pleasure can get away with a PG-13.

Such an understanding of sex and sex roles have real-world consequences.

For example, a recent study published in The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality found that cis women are more than twice as likely to perform oral sex on their cis male partners than vice versa, even though these women were far less likely to enjoy performing the act.

And as Rebecca Traister writes in New York Magazine, while today’s college women may feel freer to have casual sex with their male peers than did their predecessors, in cis hetero situations, a lot of that sex just isn’t all that good.

As she says:

Students I spoke to talked about “male sexual entitlement,” the expectation that male sexual needs take priority… Male attention and approval remain the validating metric of female worth, and women are still (perhaps increasingly) expected to look and fuck like porn stars – plucked, smooth, their pleasure performed persuasively. Meanwhile, male climax remains the accepted finish of cis hetero encounters; a woman’s orgasm is still the elusive, optional bonus round.

It also has consequences for queer and trans youth, who are so often taught to hate their bodies, desires, and identities.

Combine this with the epidemic of violence against this community, and we see a world where high school girls who identify as lesbian or bisexual are more likely to contract an STI and become pregnant than those who identify as heterosexual or questioning. Not only that, but they are also more likely to have experienced coercive sexual contact.

It means a world where young, gay cis men are targeted for violence, bullying and sexual assault regularly.

And it also means a world where transgender and gender nonconforming youth – particularly those of color – also experience high rates of sexual violence.

These situations sure don’t sound like the kind of things any of us would want for our children.

But we shouldn’t be shocked by these outcomes when we realize that we often aren’t helping reframe the standard messages about sex that our kids are receiving from so many other areas of life and that these messages help normalize the violence and discrimination that are far too common for far too many people.

Ultimately, we need to teach all our children the value both of their identities and of expecting that any sexual experience with a partner be both wanted and enjoyable for everyone involved.

3. Think About Pleasure in the Context of Consent

Though talking about pleasure is a good way to steer our kids towards better sex, expanding our understanding of pleasure is also an important component in helping them ensure that the sex they have is consensual.

That’s because if some teens just expect sex to be mediocre, bad, uncomfortable, or even painful just something that only certain bodies and people of certain identities have the right to enjoy, then non-consensual situations simply become a lot more socially acceptable.

For example, due to socialization, cis/hetero girls may not feel empowered to talk about bad or unwanted sex, and cis/hetero boys may feel less invested in ensuring their partners are fully on-board with everything that is going on.

And queer, transgender, and intersex kids may get the message they they are “lucky” enough to find other queer, transgender, and intersex kids with whom to have sex, so they shouldn’t be complaining about what that sex looks like.

Messed up, I know.

And of course, a lot of Americans simply find it tough to talk about pleasure in general.

Nowhere is this more clear than when it comes to teens whom we sexualize and then punish for exploring their sexuality.

Indeed, we are now 20 years into the government’s abstinence-only programs. These have consistently peddled shame and fear in the place of education, and they have lead to a climate where simply offering a sexually active teen a condom, an HIV test, or free birth control can be seen as a radical act.

And even when we teach comprehensive sex education, we sometimes fail our kids by ignoring the role of pleasure, and by defaulting to old-fashioned ideas about the “inherent” differences between boys and girls.

These can reinforce stereotypes, erase LGTBQIA+ and gender nonconforming identities, and hinder the work of creating a more egalitarian vision of sex.

So what should we teach teens about the role of pleasure in consent?

A lot.

Teens can learn that caring partners work to make sure that things feel good for everyone involved and that this will likely take communication, trial and error, and some awkward moments and missteps.

They can learn that sex is not a competition with a winner or a loser.

They can hear that consent is not just about getting a yes, but rather it is about ensuring that all partners want and enjoy the sex they are having.

And they can stand to be reminded that we still live in a society that tends to value the pleasure of certain bodies over others, and that they can actively work to dismantle and challenge this model in their own lives.

As Amanda Perez Leder, the founder of Communicating about Health and Tough Topics (a program designed to prepare families and organizations to talk about sexuality) explains, when young people expect sexual activity to be mutually pleasurable, they are also more willing to negotiate birth control and safer sex methods with partners.

As she says:

Expecting sexual activity to be pleasurable also encourages more frequent communication during sexual activity – and when’s there’s ongoing communication, consent gets discussed more – both before sexual activity and during.

For example, “Hey, I’d really being into this. How about you?” or “Hey, that doesn’t feel good to me, nor did you ask if that was okay. Please ask next time.”

Like Perez Leder, Holly Ponton, and Jessica Higgins of Colorado Youth Matter see a real link between how we view pleasure and consent.

They explain that the dominant narrative reinforces the notion that the primary goal of sex is for cis/hetero men to feel pleasure via the bodies of cis/hetero women and girls.

They write:

When we teach youth that pleasure in sex is only for certain bodies, we’re creating a culture of sexual entitlement: that some bodies exist solely for the use of others; that some people are entitled to use other people’s bodies however they desire; that they have the right to enforce power and control over those bodies. This directly reinforces rape culture.

The result is that many teens learn that their own greatest pleasure should come from feeling desired by someone else and not from their personal experience of sex itself.

Really, when we stop teaching kids that sex is a prize, or a game to be won by one partner at the expense of another, and we start teaching that sex should be a mutually enjoyable experience, then we are far less likely to stand for situations where one person’s enjoyment of sex is obtained regardless of the cost to the other person.

Now, About Bringing Up the Topic With Your Kids…

For a lot of parents the idea of talking about the pleasure part of sex makes them feel like they are somehow condoning something they are supposed to condemn.

But this notion is off-base and damaging.

The truth of the matter is, kids aren’t going to start having sex simply because we mentioned that everyone should enjoy any sex they are having, any more than they are going to wait to have sex until marriage because they took a virginity pledge.

In actuality, only 40% of American teens have sex by the time they finish high school these days, and research shows that the more teens know about sex, the more likely they are to not only delay sex, but to make healthier choices if they do decide to have it.

So letting them know that pleasure should be part of the equation is really just another tool we can draw on to help keep them safe.

With that in mind, here are a few tips to help you have these conversations:

- Make pleasure a key component of any conversation you have with your kids about sex.

- Include LGBTQIA+ youth in your pleasure messaging. Sexism and cis/hetero expectations of sex hurts the queer community in innumerable ways.

- Don’t just talk to kids who are sexually active.

- Try to talk about sex in non-reproductive terms. For a lot of young people their interest in sexuality has nothing to do with the baby-making part.

- Don’t pretend most people have sex to get pregnant. They don’t.

- Stop worrying about virginity and whether a someone has “lost” it through PIV intercourse.

- Don’t assume all kids are looking for sexual pleasure.

While talking about pleasure is super important, so too is acknowledging that sex with a partner(s), orgasms, or even dating just may not be someone’s thing.

That is A-OK and crucial to mention, since just like pushing the abstinence standard on those kids who would like to be having sex, pushing sexuality on those for whom this isn’t the right fit can also teach kids that their bodies and their choices about what to do with them are less important than the desires of another person.

And remember, these aren’t one-time conversations. It’s not like you can just sit down and say, “Taylor, today we talk pleasure,” mumble something about orgasm and oxytocin and call it a day.

These talks need to be ongoing and normalized. And they need to be inclusive of all genders, sexual orientations, and bodies.

Acknowledging sexuality in our children is no easy thing.

But when you think about it, neither is denying its existence.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Ellen Friedrichs is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s a health educator, sometimes writer, and mom. She has worked at Manhattan’s Museum of Sex, developed sex education curricula in Mumbai, India, and run HIV prevention programs for at-risk teens in the South Bronx. Currently, Ellen runs a middle and high school health education program and teaches human sexuality at Brooklyn College. More of Ellen’s writing can be found here and here. Follow her on Twitter @ellenkatef.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more