(Note: For the purposes of this discussion, I’ll be using “youth” to refer to folks ages 12-24.)

Them: Bring young people to the next meeting! We want to hear their voices!

You: Okay, what’s your budget to pay them for their time?

(Crickets) That is, the entire room falls silent.

Ah. So you want youth consultation. For free. But, how many of you are here for free?!?

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve experienced the conversation above in the youth nonprofit world while discussing youth empowerment.

Youth are important, youth are the future. Who’s going to disagree?

But though we love youth, how are we also working to translate that affection into respect?

A broad commitment to youth is demonstrated by a quick numbers search: the nonprofit registry Guidestar lists 36,900 organizations that identify youth development as their primary goal. That’s a lot!

But before we get too hype, we’ve got to put on our critical hats. While it’s great to ask what goods or services these nonprofits are providing youth, we need to also ask what are they doing to shift a world that chronically undervalues and disrespects youth?

What are they doing to challenge a society that is not made by or for youth?

Because, as we’ll come to understand, age, in fact, isn’t just a number. Rather, being and/or being viewed as young has dramatic implications for the way in which the world responds to us.

‘Youth’ Is More Than Just a Developmental Stage – It’s a Social Class

To make this conversation easier, I’d like to suggest a shift in how we’re thinking about youth. Typically, we discuss youth as folks at a specific point in their development.

We understand “youthhood” to be a stage we all go through in our development into adulthood. We imagine there to be at least some scientific and social truths about youth.

For the purposes of this conversation though, I’m going to ask us to think about youth as a social justice issue. I want us to think about the social justice implications of being a youth. Because just as society is structured around assumptions of straightness, whiteness, maleness, able-bodiedness and their idealization, so too is society centered around adulthood.

The societal belief in the adult as the norm, the ideal – the goal – is called adultism. Put another way: adultism is the power and privileging of adulthood over youth.

Don’t believe it? Unclear on the difference between ageism and adultism? Unsure of how it shows up in daily life? For a briefer, and some examples, check out these links.

Lions, Tigers, and Adults Running Youth Nonprofits, Oh My!

While we could spend hours chatting about the wide brushstrokes of adultism, today we’re going to focus on a place where we wouldn’t expect to see it: the youth nonprofit world.

For better or for worse, charitable organizations have long been sites at which young folks, rejected by broader society, have found some sort of care. The institutionalization of youth services really launched in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, with the Children’s Aid Society (who you might remember for their infamous Orphan Train idea) being founded in 1853.

In addition to racist, exclusionary, or assimilationist approaches to youth of color, the language of early child welfare organizations was deeply objectifying, and often supported the idea that young people should be either state or family-owned, in body and in will.

The (deeply racialized) language of vagrancy abounded, with nonprofits contributing to and capitalizing on fears of an unruly and insurgent youth underclass running rogue in the streets.

So okay, fast-forward a few centuries, and sure, the ways we discuss young people in the youth nonprofit world has shifted. You’re less likely to witness a nonprofit claiming its mission as eliminating vagrancy. Instead, words like empowerment, development, community, innovation, and access abound.

While this language is clearly preferable to ownership and fearmongering, I want to know – though the words have changed, how have the structures changed? Does a shift in language reflect a genuine shift in how adults are supporting youth?

When we commit ourselves to working for young people, are we committing ourselves to addressing the roles of adults in their pain?

Are we truly working to move ourselves offstage so that they may come off the sidelines?

How is empowerment being facilitated in a way that rejects a patronizing adult-youth power dynamic? How is development occurring so that youth are being valued not just as adults-in-the-making, but for being exactly where they are? How is a youth community being cultivated that does not include or rely on adults?

How is space for innovation being made, even when what is innovated challenges the ideas of adults? And how is access being created – actual, resourced access, not just promises that it gets better?

For those of you who work, have worked, or are thinking about working in a youth nonprofit, consider whether you’ve fallen into some of the adultist traps below. Walking through the halls of a nonprofit, have you witnessed these? If so, what was the impact it had on the young folks you work with? How did you feel about it? And what would happen if you had disrupted it?

And so I present to you seven ways youth nonprofits enact adultism:

1) Grow Up!

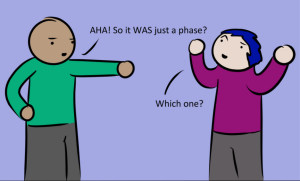

You’ll understand when you grow up. I hate teenagers. Oh, puppy love. You’re so mature for your age…

Adultist microaggressions abound in everyday language. To the adult speaking them, these phrases may feel harmless enough. But microaggressions are not about your intent.

They’re about your impact. And the impact of adultist microaggresions is a message that young people are inherently less valuable than adults.

2) The ‘Save the Children’ Approach

You know the story: a child without shoes peers into the camera as a Sarah Mclachlan voiceover pleads for just one dollar a day.

Unfortunately, it isn’t just these over-the-top examples of poverty porn that objectify young people for organizational gain. Youth’s stories are routinely exploited in the interest of nonprofit income.

An adultist nonprofit dictates that youth must be so grateful for the services provided that they must feel compelled to give back.

And that an appropriate way for a youth to give back is to publicly share traumas in the interest of cultivating donations.

It must be noted here that far too often the story of trauma is told by a youth of color while behind the scenes, those facilitating the storytelling are white (as are the targeted viewers).

In this sense, a nonprofit’s adultism is strengthened by a racist structuring of services in which the lives of people of color are whittled down to victim narratives and cast in pity for (white) organizational gain.

Consider this: What about your life would you share with a nonprofit mailing list of 5,000? Would you tell them about your relationship with your father? Your history of abuse? And if not, why? And also, then, why do we ask (or even expect) young folks to do this?

3) Over-The-Top Boundaries

Youth shouldn’t be able to see your Facebook profile. Youth shouldn’t have your cell phone number. Youth shouldn’t see your Instagram.

Adultism tells nonprofit workers that youth can’t and shouldn’t know anything about who you are as a person because you’re an “adult professional” and they’re not ready for “adult” things – especially knowing that you are, in fact, an Adult Human.

Don’t get me wrong, boundaries are very important in working with young folks. Given the power dynamic between an employed adult and a young person, it’s important to implement boundaries to ensure that the focus of any nonprofit worker-youth relationship remains on the young person. Selfhood should be shared insofar as it’s useful to the young person.

But also, I think there’s something deeply patronizing in refusing to share selfhood with youth because you believe they’re unable to handle it.

Odds are, most of the young folks you work with have regular access to conversations about the things you deem off limits – sex, relationships, substance use, abuse, politics, and so on.

In my work with queer young folks, I’ve found challenging traditional boundaries to be a useful way to model (relatively) healthy, queer adulthood – to show that it includes beautiful things but also making errors and navigating a tough world.

To deny them access to these realities is to deny feasible futures, in a sense.

4) Pizza Is Cute But It’s Not Cash

If you’re asking youth to perform labor you would pay an adult for (office work, testimonials, consulting, community outreach, or group co-facilitation), it’s inappropriate to expect a young person to do it for free.

Adultism tells us that youth need learning experiences or skill development before they reach the point at which they can become a “paid adult professional.” But just because someone hasn’t yet passed geometry class doesn’t mean their labor is worth any less than that of an adult.

Many young folks we work with are without financial resources. Others are using any income they receive to support their family.

Expecting them to do organizational labor for free perpetuates cycles of poverty that keep adult nonprofits above ground and youth in need.

So besides the fact that their work is just as deserving of compensation as adults doing the same work, if your mission is oriented toward access, it’s the right thing to do.

5) Mandatory Attendance and No Phone Policies

Much like adults, youth have competing interests that make full participation in non-mandatory activities challenging.

Ever missed a workout class? Texted during a book club? Ran out of a meeting to take an important phone call from a friend or family member?

Did these spaces punish you for doing so?

Adultist nonprofits penalize absences or level consequences for phone use when they are grounded in the assumption that youth are untrustworthy, uncommitted, lazy, or not serious.

In actuality, youth are balancing similar commitments to adults: work, friends, family, school, budget. Perhaps a youth’s grandparent isn’t feeling well and they need to miss out to take care of them. Maybe they need to be available to a friend in crisis through text.

And maybe something is going on that they’re not ready to talk to you about, but that means they can’t come today. Their priorities may not be yours, but that doesn’t mean they’re not right.

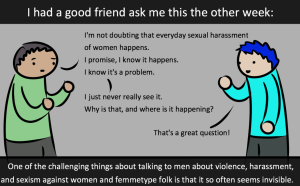

6) Collaboration with Harmful Systems

Some systems have adultism more strongly wired into them than others, and it just so happens that these same systems tend to also be structured to penalize people of color, LGBTQIA+ people, non-citizens, and other identities that young people hold.

When a youth nonprofit collaborates with a system, be it to hold an information session, or career day, or meet and greet, they’re co-signing the position of that system.

When a youth nonprofit brings in a police officer, they’re co-signing stop-and-frisk policies that disparately target youth of color. When a youth nonprofit brings in a business notorious for disallowing youth in the store, they’re co-signing the belief that youth are thieves.

And when a youth nonprofit brings in a government representative known for passing legislation that closes youths’ schools and opens prisons, removes funding from job opportunities for youth, deports the parents of youth, eliminates transgender youths’ access to healthcare, or similarly targets youth, that nonprofit is co-signing those efforts to strip youth of their rights.

Be mindful of the messages of your collaborators. Think carefully about the “opportunities” being presented by your guest, and what sort of sacrifice they might require on behalf of the youth.

7) Rescuing

Again, this one isn’t just for Save-the-Children commercials. Rescuing is ever-present in youth nonprofits.

We need to get them out of that family. Yes, but do you have an apartment for them?

We need to get her out of sex work. Have you asked if she wants to get out? What job do you have lined up? Does she want that job?

We need to get him back in school. Where he isn’t safe?!

Paired with capitalism and a middle-class value system, adultism drives nonprofit workers to make decisions on what is best for a young person. And, upon making those decisions for them, to take at least partial credit for “saving” that youth.

Rescuing implies that someone has been removed from their life and placed into another.

Instead, the appropriate approach to goal setting for youth is to create goals that are self-directed and supported by adult allies – not that are directed by adults and supported by a youth’s behavior.

While we’re on the topic, a quick PSA:

The sharper side of the rescue sword is in the language of ownership used by many nonprofits. How many times have you read a newsletter that referenced “our youth?” Map that onto another demographic – how would we respond to a male-run organization that referred to participants as “our women”? Not well, I imagine.

What to Do Instead

Adultism isn’t (yet) a broadly discussed social justice topic – meaning that you’re on your own for generating creative ways that you can show up as an adult ally in your work at youth nonprofits!

While we work on that article, however, consider the following points of engagement as you imagine how to move from being a top-down support for youth to a true accomplice.

- Understand that youth know things you don’t. Extend respect to their expertise and ask how you can support the lives they desire for themselves.

- Always, always, always use an intersectional lens! How is your adult-youth power dynamic layered with race, gender, sexuality, class, citizenship in your nonprofit? Who holds power and where?

- Sometimes this means sacrificing expediency and profit. But in the end, who does expediency and profit truly serve?

- Real youth leadership means deferring to their decisions, even when they’re not the ones you’d make. Allow youth to tell you what’s important.

- Compensate!

- Reflect on yourself: How does your adult privilege show up in your relationships with youth? How are you invested in this power?

- Oh, right. Compensate!!!

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kel Kray is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. Kel is a fiercely friendly social justice warrior who spends their days advocating with and on behalf of queer youth at an LGBTQIA+ youth center in Philly. A firm believer in the transformative power of dialogue, Kel coordinates a youth-driven education and training program that facilitates community workshops on gender and sexuality with an intersectional lens.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32