Originally published on The Body Is Not an Apology and republished here with permission.

Growing up in Peru, I was taught to be very proud of my heritage.

I grew up hearing stories of my people from my teachers, my mother, and my grandmother. They would often tell me to be proud of where I came from, but they would also then compare our ancestors to the current state of our country. “How could we have been so wise, only to now be struggling like this?”

I would ponder about the situation of my homeland as I traveled back and forth between the gated communities of La Molina, to the streets lined with burning trash on the way to my grandmother’s house, in Independencia.

In my classroom we had pictures of Jesus and Tupac Amaru, and our teachers would talk about the technology of the Spaniards as well as the devastation that the conquistadors brought to our homeland.

In Lima, I would stare at the statues of generals and war heroes, those that supposedly brought us our “independence,” but were we really free?

At the age of twelve, my family was forced to migrate to the United States, where I was asked over and over and over, where are you from? It’s been fourteen years since then, and yet I still ask this question to myself everyday: Where am I from? Where are any of us from?

The term “settler colonialism” wouldn’t enter my vocabulary until about three years ago. Having never gone to college, I’ve always felt wary of academic terms, and so it took me several attempts to understand what being a settler means, or what it means to me anyways.

When we talk about settler colonialism, we aren’t talking about race or class, we’re talking about land and theft, and the 500 years of rezilience in which Indigenous people have been fighting back and standing their ground, all across the globe.

To be a settler is to not be from here. Yet, even as a settler, I’m not a pilgrim. My people didn’t come here to assimilate back into the system that pushed us out of our homelands in the first place, and our migration was not an act of greed. It was a bold yell against those who have silenced our truth for so long.

The migration of Indigenous people across an Indigenous continent is not just powerful, but also the fulfillment of a prophecy made hundreds of years ago, before the first contact with the conquistadores.

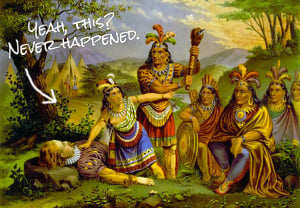

This prophecy is known as “The Condor and The Eagle,” and tells us that when the eagle of the north flies with the condor of the south, there will be harmony on the land.

This union of nations coincides with many other prophecies made surrounding the topic of not just “harmony,” but of an awakening of the people, and it’s been my own personal awakening that has stirred in me a sense of responsibility: Yes, we are settlers, but we must refuse to become part of the machine.

I didn’t leave my homeland to become friends with those who hunt down my people, to pledge allegiance to a system that was established on slavery and death.

I came here to survive, and the survival of my body means the survival of my culture. Like my sister Alas says, “We can never be free while this land remains stolen.”

Being a settler on stolen land means having a sense of privilege and responsibility, but most of all, a sense of purpose.

I’m separated from my homeland by borders forcibly established onto land that is forcibly separated from its resources. Like the water mined for fracking, my people are being mined for their labor.

By choosing to be intentional about our actions as settlers, we can help to break the cycles of colonization, and instead choose to use our bodies as tools against the system.

Decolonization is a lifelong process, but every generation brings us closer and closer to each other.

As the recent presidential election is teaching us, history is made in minutes, and history is made by action.

The history of this land has belonged to the colonizers for too long, and it is up to us, as Indigenous settlers, to build a new world alongside Indigenous natives.

This new world is already being built, in many ways.

I remember on the day after the election results were revealed, I woke up and lit a fire inside the stove, to make sure we stayed warm. I had been staying at Standing Rock for the past few months of my life, and had become disconnected from the everyday realities of living in the United States of Amerikkka.

I stumbled sleepily towards the firepit, where several others were already smoking cigarettes and having breakfast. “Who won?” asked my friend, who like me had just woken up. “Trump,” said a voice in the crowd.

All I could think to say was “oh,” as I stared at the faces around me. They had seen police officers attack women in the middle of prayer, had witnessed the violent means in which this country strives for “progress.”

I knew that this new presidency meant everything and nothing, that politician after politician had promised and lied to their people and my people from the very beginning.

I knew that this was just another link to the long chain of white supremacy and capitalism.

I remember walking away and finding another way to make myself useful, the cold winter had instilled in us a sense of urgency. We were all responsible for keeping each other warm, just as we were all responsible for keeping each other safe.

A lot of people talk about the magic and energy that comes from the sacred land of the Sioux. It’s true, the land shows you that another world is possible, that we’re able to create connections and actions that go beyond our lifetime, that it has been our rezistance that has led us here, and it will be our rezistance what will lead us into a future beyond colonization.

The land reminds us also of its people, its history, its bloodshed, its hurt, its pain, its fury, and its ability to heal.

It’s so important for us to remember our own ability to heal.

On the drive back from Standing Rock, I held myself as tears rolled down. The water had reminded me of my privilege and my responsibilities to the land and its Native people.

Not only must we not become part of the machine, we must be the wrench that breaks it, the tool of reparation and restoration, the reinforcement the powers that be didn’t count on, in this war against colonization.

This is what they didn’t want. They didn’t want us to work together. They wanted us to forget that our eyes and our cheekbones and our blood all travel back to the rivers. They wanted us to forget that our tribes told stories of our union since before our time.

They wanted us to forget about our power. But our power is stronger than their lies.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more