“Well, that was pointless,” I chided myself after thoughtlessly passing the puck in front of our net. I hustled to the benches for a change, vowing I’d look before I passed my next shift. My teammate was waiting. “I was watching your play, and next time you could…”

He shared how I shouldn’t pass in front of our net.

While I appreciated how he cared that I succeeded in this recreational in-house league, I was tired of nodding along to his teaching points every week. I let him take a breath, and said, “I’ve played hockey for fifteen years. I don’t really like advice.”

“Oh,” he said and fell silent.

This teammate was one of countless male players who’ve tried to teach me about ice hockey, unsolicited, over the years. Coaches not included.

I skated on a co-ed team through high school and noticed the boys I’d played with since about age nine progressively had more tips for me.

I needed to pass to specific people more. Let them cut in line for drills. Do the three-man weave differently. I had male teammates yell at me when I messed up at practice.

At first, this input fired me up. I played more aggressively to beat the know-it-alls. Eventually, though, as it happened again and again, I started to feel unwelcome.

Similar experiences are widespread among women and femmes who are into sports.

Guys like to explain strategy, teams, rules to us, even if we already know. They discount what we have to say about sports. Sometimes they don’t even understand the sport too much themselves.

This is the basic idea behind mansplaining, where men condescendingly lecture women and femmes something they already know.

Rather than having a conversation on equal ground, men who mansplain steamroll folks and assume that because of their gender women and femmes don’t know what’s they’re talking about.

Last year, a Martin A. Bentancourt tried to advise Olympic cyclist Annemiek van Vleuten on how she could’ve avoided three spine fractures and a severe concussion from a crash if she knew “the first rule of bicycling.”

Pia Glenn, xoJane writer and performer, had a man stand behind her at the gym and say she should lift less weight because, “You don’t want your arms to look muscle-y, do you?!?”

A few years back, Men’s Health even published a guide (that it later retracted) called “How to Talk About Sports with Women.”

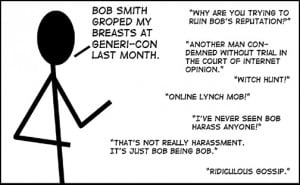

Shireen Ahmed has heard a lot of condescending comments on how she should handle rampant harassment as a sports reporter. In other words, guys have mansplained how she should handle mansplaining.

As Ahmed tells The Cauldron:

Mansplainers instruct you what to do and how to protect yourself based on zero understanding of what you are going through as a female sportswriter. If she decides to stand up for herself, she is ‘feeding the trolls.’This is basically men telling a woman that, instead of defending her work, it is best for her to be silenced.

“It’s ridiculous,” continues Ahmed, who faces racist and sexist harassment as a Muslim woman of color. “Defending one’s work and reputation is a part of sportswriting.”

Mansplaining in sports is more than annoying. It reflects larger assumptions too many people have about women and femmes and what we’re capable of athletically.

Here are a few reasons guys should consider asking for permission before they advise women and femmes on how to watch, coach, play, and write about sports.

1. Mansplaining in Sports Reflects Society’s Hidden Biases

Some men who mansplain sports seem to have good intentions.

Maybe they think explaining strategy to a teammate will help their team win a competition. They may be an enthusiastic fan eager to share what they know. Furthermore, they may not consciously single out women and femmes for their lectures.

However, good intentions don’t stop harm from being done. Sexism and other -isms are already so prominent in sports.

One international study found the United States to be the biggest offender of anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiments compared with other developed countries, for instance. This rampant gender policing goes hand in hand with sexism, trans-antagonism, and racism.

Though it may seem trivial, mansplaining in sports is like a canary in a coal mine. It calls attention to oppression.

Ignoring the roles that race, sexual orientation, gender identity, and other factors play in different folks’ experiences means that bigotry exists, unchecked.

2. Discounting Women and Femmes’ Physical Abilities Is a Factor in Sports’ Gender Representation Gap

Mansplaining’s prevalence calls attention to the fact that sports are still, frustratingly, a largely male-dominated industry.

Forty-five years after Title IX passed, women – not to mention non-binary folks – still fall behind men in sports participation.

The uneven standards start early.

The CDC reports kids ages six to eleven don’t have significant gender differences in strength, but girls still have lower requirements for physical education testing compared to boys.

It’s important to note studies like these, unfortunately, tend to rely on gender assigned at birth, so they fall short in accounting for trans and non-binary children. We can safely assume that most of the data refer to cisgender kids.

However, what these incomplete statistics reveal is still condemning.

Girls drop out of sports by age fourteen at twice the rates boys do. That is, if they even had the chance to participate. Fewer than two-thirds of African American and Latinx girls and half of Asian girls do.

No wonder when everyone grows up, men make up 90% of the sports media industry, their competitions get 98% of ESPN’s screen time, and pro male athletes get paid substantially more than female ones.

Even tennis superstar Serena Williams earned $495,000 for winning a tournament compared to men’s champion Roger Federer’s $731,000, according to Ben Rothenburg at The New York Times.

There are no statistics for femme non-binary folks, whom the sports world struggles to include anyway.

So often we don’t notice the role gender plays when men are the default participants.

Think of how many professional men’s teams compete in leagues that don’t mention their gender, like the National Basketball League and National Hockey League. In the meantime, women athletes play in leagues called the Women’s National Basketball League, Women’s National Hockey League, and so on.

Even at my high school, I competed in varsity track and field and cross-country as a “Lady Vandal.” The boys were not “Gentleman Vandals.” Either specification is silly, but if you’re dedicated to clarity, why not go all out?

Mansplaining in sports is similarly overlooked because it’s so pervasive.

Coaching girls, I’ve heard a fellow coach say that boys tended to have better hockey sense because girls weren’t “students of the game” like them. He meant he didn’t see as many girls watching games on their own.

I wish I told him it’s easier to get into watching sports when everyone looks like you, people encourage you, and you can have dreams of pursuing a lucrative career.

3. Mansplaining Helps Women and Femmes Internalize Sexism

Among stereotypes of women and femmes who like sports is the “cool girl.” She’s just “one of the guys,” usually conventionally attractive, able-bodied, white, and straight, and she’s chill enough to chow down on chicken wings and banter during the Super Bowl parties.

She doesn’t ever bring the mood down to talk about gender inequity. She may echo thoughts that women’s sports are less popular because they’re less exciting.

We can’t shrink anyone to fit any narrow stereotype. However, some women and femmes who love sports do adopt internalized misogyny. I did.

In fact, I remember becoming irrationally furious weight-lifting, as a teen, when another girl bench-pressed more than me that I doubled the number of squats she did and got a school record to spite her. I’d told myself that getting “beat by a girl” was shameful, even though I was one.

It’s easy to see how all that ambient sexism can make someone feel like they’re an exception.

When a guy moves to explain sports to them, it’s an easy defense to say, “I’m not like other girls/femmes.” It feels good when their team finally seems to accept them because they’ve been working hard enough to seem to escape their “helpful comments.”

They may start thinking other targets just need to work harder to prove their explainers wrong – and may start explaining sports to other women and femmes themselves.

Maybe it’s not mansplaining, but it may still manifest among hierarchal lines: a thin person explaining to a fat person, an abled person explained to a disabled person, or a white person explaining to a person of color.

On the flip side, mansplaining can also make you think your sports knowledge is worse than you thought.

Psychologists talk about stereotype threat, where other people’s assumptions about you contribute to how well you do. If those around you expect you to fail, you’re more likely to do so.

I’ve experienced both effects.

Not playing on an exclusive women’s team until college, I always felt like I needed to skate faster and check harder than all the other girls on my team and saw myself as inherently stronger – which I’ve realized too late is sexist BS. I’ve also seen my play degrade as men kept pulling me aside to “help.”

4. The Sexism Behind Mansplaining Stops Women and Femmes from Succeeding

Often, mansplaining has its roots in benevolent sexism, which argues that men are there to take care of women. (Again, non-binary femmes are out of the conversation.)

While people of all genders should watch out for each other, focusing on protecting women’s well-being alone assumes that women are incompetent or incapable of doing so themselves.

This relies on outdated views on gender, where cisgender women are weak, or at least underestimated physically, and cisgender men are strong.

This attitude holds back all women and femmes. Katelyn Burns writes of how trans women athletes can hold themselves back because cisgender people inaccurately claim they have unfair advantages compared to cis women.

5. Mansplaining Perpetuates Rape Culture Among Athletes and Sports Communities

When things like predatory “locker room talk,” excusing gendered harassment and assault, and sexualizing female athletes are normal, speaking to women and femme athletes like they don’t know what they’re doing makes sense.

Thinking sporty women are the property of straight men leads folks to ask motorcyclists like Lily Brooks-Dalton taking cross-country trips if they left their husbands at the campsite, for one.

Maia Deccan Dickinson writes in Runners World how most media calls women runners targeted by crimes “joggers.”

She explains how this word can imply victim-blaming, as jogging means moving at a “gentle, slow pace,” compared to the mightier word “running.”

Dickson writes:

If a male ‘jogger’ is run down by a car, does the term cause the reader to trivialize his athleticism – to question if a finer athlete might’ve outrun the car? No. If a female ‘jogger’ is yanked off a trail and raped, has the word ‘jogger’ made a statement, implying a gentle, slow pace, a less-serious athlete – a target for attack?

Perhaps. Speed and strength are irrelevant to the crime – the athletic equivalent to a report of campus rape that mentions the victim’s outfit or alcohol consumption. It is not important how fast any of these women were running.

It is important that the default language used to discuss these attacks suggests that it was slowly; that when learning of a moment in which a woman’s strength was called upon to defend her very life, we read a word that undermines it.

The least we can do in the aftershock of these events is give due credit to these women who, when assaulted, were increasing their physical strength and stamina in a culture that still, in its darkest moments, tests these limits.

***

Mansplaining is prominent in sports, but it doesn’t have to be.

Team sports, in particular, intend to lift up individual players for the sake of the team. If we start recognizing how privilege plays out on the rink or field, we can begin to confront it on a micro-level.

We can stop ourselves before we go into knee-jerk explanations that can damage a teammate’s performance and confidence.

We’re all only as good as our worst player after all, and cutting the sexism can make us all play better.

We often need privilege to play sports. If we manage to get out there, let’s not make it harder than it already is.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Emily Zak is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism and a freelance writer based out of Santa Fe, New Mexico. She writes extensively on LGBTQIA+ issues, and her work has appeared on Ms. Online, Bitch Media, and Care2, among others. Follow Emily on Twitter @EmilyEZak. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32