In-focus person standing among other out-of-focus people on the street.

This article was originally published in The Establishment and was republished here with permission.

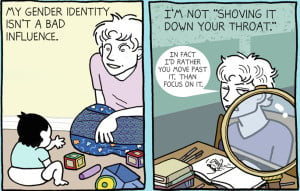

“You’re not trans. You’re just a transtrender!”

If non-binary people had a nickel every time we heard this, we’d be rich enough to hop a rocket and start our own space colony on Mars. But alas, we’re stuck here on Earth, constantly explaining to everyone what it’s like to not identify within the gender binary.

The “transtrender” argument is rooted in the belief that since non-binary people aren’t transitioning to the opposite biological sex, we must not experience gender dysphoria (defined as “a conflict between a person’s physical or assigned gender and the gender with which he/she/they identify”). Therefore, we’re just co-opting trans language to be hip and cool.

This is, in a word, bullshit — and while I expect it from those who are cis, it especially hurts coming from trans people.

Certainly, I understand the need to keep the “this isn’t just a feeling” narrative alive. Transphobes, after all, love to say things like, “Well I feel like a tree, so does that make me a tree?” — despite the number of studies that suggest a scientific basis for gender identity. But why can’t binary trans people understand that, just as they don’t identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, some people don’t identify with “man” or “woman”?

Interestingly enough, the DSM-V describes gender dysphoria in a way that includes non-binary people. Under the list of symptoms, the DSM-V lists strongly identifying as, wanting to be treated as, and having the same feelings as either the opposite sex “or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender.”

Well, that pretty much describes me. I’m not just an androgynous man; my entire sense of self and my experiences do not align with my assigned gender. When I was a child and socialized with girls, I felt like I was one of them. As far as my body goes, it’s complicated. I’m fine with my chest and genitals, but my body hair feels like a foreign object that’s infesting my body.

After talking to several of my non-binary friends, I found they experience similar forms of dysphoria where they are comfortable with some parts of their body, but not others. Could it be that this is the case for many, if not all, non-binary people? There was only one way to find out: the scientific method!

I sent out a call on both my Facebook page and a private Facebook group asking for non-binary people to participate in an eight-question survey. Ten people responded, so I private messaged them the questions.

Within a week I got all the results back, and it turns out I was right — non-binary people do have unique experiences with dysphoria.

According to medical experts and accounts from the trans community, most trans people start experiencing dysphoria around puberty — and the same seems to be true for non-binary people as well.

“I figured something was off [at age] 10,” says Kay, “but it wasn’t cemented until someone called me a man around three years ago, and I involuntarily cringed.”

“I always knew I was ‘not like other girls,’” adds Naseem, “but I didn’t start experiencing dysphoria until I hit puberty, which began around age 9. By 11, when I started my period, I had 100% developed dysphoria. By 14, when I started high school, I was already saying that I should have been born a boy, calling myself ‘a gay man in a woman’s body.’”

For some, puberty was when they first began feeling that neither “boy” nor “girl” really fit. Amy says, “I didn’t feel like I fit in with girls or women from the time I was maybe 8 or 9, but I didn’t fit in with boys, either. I didn’t know being gender fluid was a thing until I was in my late thirties. It explained a whole lot.”

In fact, some participants reported having dysphoria that was more mental than physical in nature. Says Jude:

I have a very androgynous body, so it quite suits my gender. I’m lucky. But being forced into femininity so long caused me great distress. I’m genderfluid and sometimes feel feminine, but other than that I never dress feminine, so as not to put myself in a position to be dysphoric. It would trigger my mental illness symptoms, which are anxiety and dissociation mostly.

As far as whether the participants were uncomfortable with some parts of their body, but not others, most of them said yes. “I love my breasts most of the time,” says Amy, “and I would never want them gone. But I absolutely do wish I could alternate genitals, and I would love it if I weren’t so curvy. I don’t mean fat (even though I am). I mean smaller hips, less hourglass.”

Kay says they’re fine with their genitals, but their dysphoria is “largely chest centered.” Danielle says their dysphoria led to an eating disorder. “I wanted to attain a small straight waist like my male friends,” they say, “but my body was and is curvy.”

As far as how intense the dysphoria is, nearly all participants said it fluctuates based on circumstances. On a scale of 1 to 10, Ingrid says their dysphoria ranges from 5 to 10 on average. Amy says some days they feel “100% comfortable,” but some days they “don’t even want to be seen.”

“My dysphoria fluctuates almost hourly,” says Daylin. “I can feel fine, look in a mirror, not like what I see, and my day is ruined. The good thing is, I seem to have the ability to turn off my dysphoria subconsciously when I’m going to work. I’m not sure why this is, but it’s obviously very useful.”

As with many binary trans people, some non-binary people do undergo medical transitioning. Both Ingrid and Daylin currently take hormones and hope to get both top and bottom surgery in the future. Most of the participants, however, are still up in the air about transitioning. “If I decide to have children,” says Naseem, “I would ideally like to breastfeed, and there doesn’t seem to be enough informed doctors to do a top surgery in a way that would allow me to do so.”

Despite mixed feelings about medical transitioning, all the participants responded that changing their pronouns and presentations has made all the difference. Says Jude:

Mostly I wear masculine clothing. I have a ‘men’s’ haircut and all. I talk about it to people I trust. In the workplace and the world I pretty much let it go, though it seems like people perceive me as a man almost as much as a woman and they don’t know what to make of it. I still get gendered as she, like I said, almost exclusively, but people often remark about how I’m ‘a dude’ and things like that.

Naseem also notes a significant change in recent years:

Ever since I discovered the term ‘non-binary,’ my dysphoria has become almost completely manageable. Just having a name for how I felt made me feel that much better. When I realized that I identified as trans and started using they/them exclusively — only from the beginning of this year, even though I discovered [the term] NB three years ago — a lot of that also subsided.

I should point out here that I’m not a scholar, and that my sample size was pretty small; this is obviously not akin to a peer-reviewed science journal article. Still, I hope this experiment provides some insight into the unique ways non-binary people experience gender dysphoria.

Ideally, medical professionals will take dysphoria in non-binary people more seriously in the future, and give non-binary people proper medical care. And with deeper understanding, I hope there will come a day when I, and other non-binary folx, no longer have to answer respond to accusations of being “transtrender.”

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32