Maybe it happens when you’re all sitting at the dinner table and someone brings up the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or as the program is more commonly known, food stamps.

It might be that your uncle thinks most people who receive SNAP benefits are “lazy” and don’t want to work. Or maybe it happens when you pull into a shopping mall parking lot, and your friend sees someone get out of their car and says, “That person is parked in an accessible spot, but I don’t see a wheelchair. I guess they’re faking!” This is what ableism looks like.

Ableism is everywhere and many people are simply unaware of it. There’s a seriously good chance that your loved ones and community members are ableist sometimes.

We’re all raised in a society that’s built on ableist values that are also linked to white supremacy, capitalism, and colonization, which is why the people we love sometimes have oppressive views.

But we’re also all capable of growth and change, and one way that we can do better is by talking to people when they express an ableist view.

If you’re disabled, it shouldn’t be your job to constantly educate non-disabled friends and family, but sometimes you may need to in order to survive. And if you’re non-disabled, this is one way you can do your part to be an active ally.

Here’s a short list I came up with that covers how you can talk to your community and loved ones about their ableist views, especially if you’re having the conversation in the moment after their views come up.

1. Know the misconceptions and the facts.

It helps if you come to the conversation prepared. Understand some of the common ableist myths and misconceptions that people believe.

Read the work of disabled writers and activists on some of the common misconceptions they face. Are there ableist phrases you didn’t realize were oppressive?

Learn about common forms of ableism that repeatedly happen in our society. If there’s a particular issue that you’re not sure about, take the time to find out.

For instance, even though I’m disabled, I didn’t have an in-depth understanding of how difficult the process of being recognized as disabled by Social Security is. I’ve never been a recipient of Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability, and I’d heard from others in passing that it was relatively easy to fake a disability.

I wanted to be able to talk about this with authority with others in my life, so I learned more. I read about the reality of the process for actual disabled people and how challenging it is to have a legitimate disability recognized.

I did my own research about the application process and how many cases have to be appealed, what the success rates are, and how long it can take to get an approval. The more well-prepared you are to have conversations about ableism with your friends and family, the better.

It helps if you have an understanding of where they’re coming from. Where are they learning these ableist views? Are they seeing these things in the media? Are they hearing it from other people in their communities?

The more you know about your friends and family’s ableist views and where they come from, the more you’ll be able to connect with them when you talk.

2. Decide if you want to try calling them in.

“Calling in” is an alternative approach to calling out. “Calling in” can be an effective way to talk about someone’s ableist views with the aim of changing their problematic behavior.

If you have the energy and capacity to call someone in, especially if you’re not disabled, it can be really useful as a way to educate that person about their ableist views.

I’ve had to call people in about disabled people using accessible services without a visible mobility aid. I know that they’re getting their information from the media — for example, there are a lot of depictions of people faking disabilities in order to use an accessible parking spot, since those spots tend to be closer and easier to find.

Many people are unaware that invisible disabilities exist and what those disabilities look like. It’s not my job as someone with a mobility impairment to educate them, but when I have the energy and emotional bandwidth, I sometimes will.

I’ll explain how I’m impacted by my disability and how it becomes invisible when I don’t have my cane with me. I’ll tell that person that although I don’t currently use accessible parking spots, many people with my disability do.

I offer them reasons why people with invisible disabilities may use accessible parking spots: the person may have severe pain and fatigue, they can walk but not for long distances, or being out in the cold for more than a few minutes can have negative health consequences.

If you decide to call someone in, there’s a real possibility that they’ll have questions and want to talk through the scenario with you, so make sure that you have the energy to handle that or you’re comfortable telling them, “I can’t continue talking about this right now, but I have some resources if you want to learn more.”

3. Offer them outside resources.

Unfortunately, people often turn to marginalized people to be educators on our own oppression and expect us to do all the emotional labor of empathizing with them and providing them with knowledge.

When you encounter ableism and possibly other forms of oppression on a daily basis, this can be exhausting. This is where resources come in.

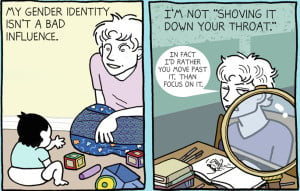

Tons of people have done and continue to do the work of creating information about ableism. Depending on the person, you can point them to blogs, YouTube and other videos, longform articles, academic research, documentaries, and comic strips.

As a disabled journalist, I’ve created a lot of my own resources on ableism, and I’m aware of a lot of other resources that exist. I’m constantly sharing these things on my own social media channels in the hopes that they’ll open someone’s mind or expose them to a reality they didn’t know about before.

I also have these resources in mind for if I get into a conversation with someone about a specific subject, like accommodations in college classes, so that if I need to take a step back from the conversation, I can leave them with places to learn more.

A lot of people won’t seek out these resources on their own, but might check them out if you talk to them first or share the resources on social media. They might be swayed by the fact that someone they know and trust has interacted with the resource and found it useful and trustworthy.

***

As someone with a disability, I’m often exhausted by all the emotional labor I have to do just to exist in this world, especially when I’m constantly educating others about ableism and trying to get them to unpack their own ableist ideas.

It makes my life so much easier when non-disabled allies and community members step in to have these discussions with their friends and family, too. It’s a real action anybody can take to be a loving ally to the disability community, and it benefits all of us when we move toward an inclusive, accessible society free of ableism.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alaina Leary is an editor, book publicist, and activist from Boston, Massachusetts. She’s a social media editor for the nonprofit We Need Diverse Books, and has an MA in publishing from Emerson College. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The Boston Globe Magazine, Teen Vogue, The Washington Post, Vice, Cosmopolitan, The Rumpus, and more. Twitter/Instagram: @alainaskeys.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more