Source: United Community Services

Trigger Warning: Sexual Violence and Rape Culture

It’s been heartening to see the ways that sexual violence is being discussed more comprehensively and holistically in public discourse these days. More than anything else, the credit for this development rests with the brave survivors who are choosing to speak out and tell their stories while pressuring colleges, universities, and all levels of government to be more responsive to the needs of survivors.

From Know Your IX and SurvJustice, to brave individuals like Zerlina Maxwell, Angie Epifano, Wagatwe Wanjuki, and the countless others who are stepping up to share their stories, we’re witnessing a movement.

This movement has transformed many universities’ approaches to sexual violence prevention and response, and it has even made it to the U.S. Congress and the White House, with Obama standing up for all survivors of rape in a way no other U.S. president has done:

Yet whenever a movement for justice makes strides forward, there is the inevitable backlash.

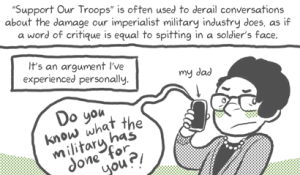

You’ve got the Todd Akins of the world trying to parcel out what’s “legitimate rape.” You’ve got the Glenn Becks (or at least his employees) mocking people whose experiences with sexual violence don’t match their narrow concept of rape.

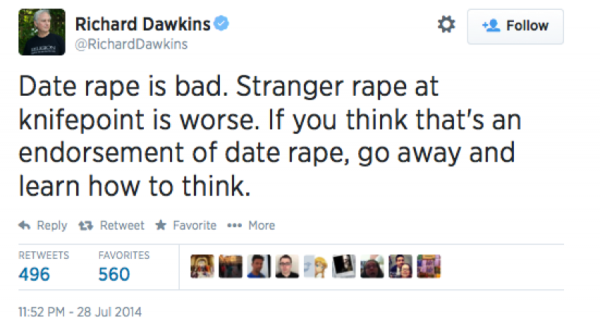

More recently, resistance came in the form of a “logic puzzle” of sorts from the ever-infuriating, self-appointed spokesperson for all atheists, Richard Dawkins:

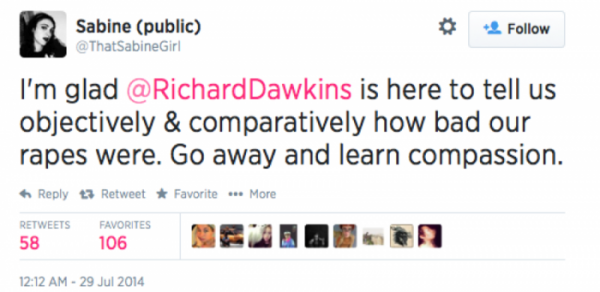

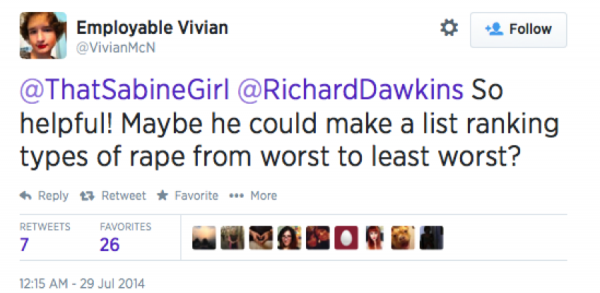

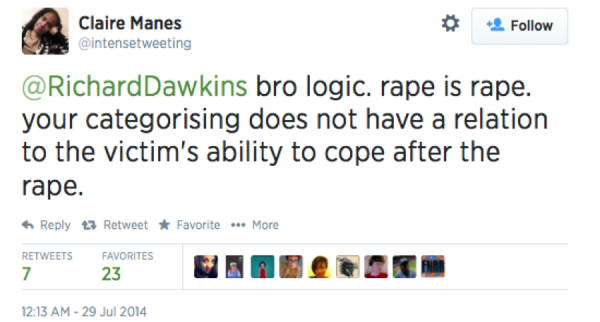

Fortunately many people spoke out powerfully against Dawkins’ “example:”

These conceptions of sexual violence attempt to lay people’s trauma on a spectrum with one end being “shut up, it’s not that bad” and the other end being “legitimate rape.”

All this ends up doing is denying the realities and pain of survivors.

Simply put, this is perpetrator logic. Perpetrator logic says that the person impacted doesn’t get to say whether something was traumatic. The only opinions that matter are those of the perpetrator and those who defend their actions by writing off some violence as “lesser” than others.

Perpetrator logic claims that rates of sexual violence are exaggerated by feminists who define the term too broadly. After all, defining “rape” so broadly might actually mean that I’m a perpetrator of violence, even if it didn’t look like what I picture a rapist to be.

The impact of perpetrator logic, then, is the silencing of survivors. When you know people won’t believe you or give you the public and private support you need to heal, you’re far less likely to share your experience, even with loved ones.

When you’ll be shamed and questioned, you are far less likely to speak out publicly about sexual violence.

And when you know you’ll be treated like you’re the one who did something wrong within the legal system, you are far less likely to report to the police. And some wonder why rates of reporting are so low!

Collectively, we need to move away from perpetrator logic. We need to move away from that logic which attempts to define for survivors what their experience was, and we need to empower more survivors to find the healing they need.

Here are four important things we need to do in order to abandon perpetrator logic.

1. Understand That Sexual Violence Is a Matrix of Behaviors

For many people, it might be tempting to create a spectrum to describe sexual violence, sort of as Dawkins attempted to do in his tweet. After all, this is precisely what our criminal “justice” system does in deciding whether to press charges and what charges to press. In this spectrum, some behaviors are patently “worse” than others.

In reality, though, sexual violence is better understood as a matrix of intersecting behaviors, many of which can be taking place simultaneously, all of which serve to exert power over and to hurt the survivor (or victim in those tragic cases when the person does not actually survive).

Myriad behaviors are or can be sexual violence: abusive language, street harassment, ritualistic abuse, forced penetration, forced kissing, coerced sex or touching, childhood sexual abuse, other violent childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, threats of violence, murder, forced consumption of pornography, taking sexual photos without the person’s consent, sharing sexual photos without the person’s consent, and countless other acts.

All of these behaviors (and others not listed) have the power to traumatize the person impacted as well as “secondary survivors,” those who know the survivor and are impacted by their hurt.

There are intersections of this matrix where multiple forms of violence are used at once, and there are times when only a single act of violence is perpetrated, but all of this violence exists within the context of a rape culture that commits daily violence against countless people in our society.

Regardless of what that violence looked like, it makes absolutely zero sense to compare people’s trauma.

After all, violence perpetrated against one person can results in life-long PTSD, but a similar act of violence can impact another survivor wholly differently—but that does not make that act or any other “more” or “less violent.”

What matters is how the survivor is impacted and what they need to heal.

2. Empower Survivors to Name Their Experience

In a society that dictates constantly to survivors what their experience “actually was” or whether what they are feeling about their assault is “legitimate,” seeing sexual assault as a matrix of intersecting behaviors is revolutionary for one simple reason: it empowers survivors to name their experience for themselves, which is a first step in healing.

In training to become a sexual assault survivor’s advocate, one of the foundational things we learn is that we must empower survivors to name what happened to them in their own language and on their own terms.

This simple act grants some measure of power back into the life of someone who has had all control removed for a period of time. It allows them to control how they and others understand what happened to them.

If a survivor describes what happened and then asks if what they experienced was rape, we might turn the question back to the survivor, asking, “Is that what you’d call it?”

If they’re still not sure, perhaps we talk to them a bit about sexual violence being anything that violates their boundaries and consent, offering them language to then name what happened, language they can pick up, turn over in their mind, and keep if they feel it applies to their experience.

In all of this, though, the survivor is in the driver’s seat.

This is vastly different from how most of our society treats survivors, as they are met with, “Did you see what she was wearing?” or “But men can’t be raped” or “Maybe you just regret going that far with them.”

3. Recognize That Healing is a Spiral

For many survivors of sexual violence, the simple act of being able to name one’s experience irrespective of what others might call it is a first act in reclaiming autonomy and agency when those things have been violently taken away. And that is often the first step in a process of healing.

Unfortunately, we often talk about healing with the same problematic “spectrum” metaphors we use for violence, with “broken” on one end and “healed” on the other.

Much like naming survivors’ trauma as existing on a spectrum, this doesn’t empower survivors because it doesn’t describe what most survivors’ healing journeys looks like.

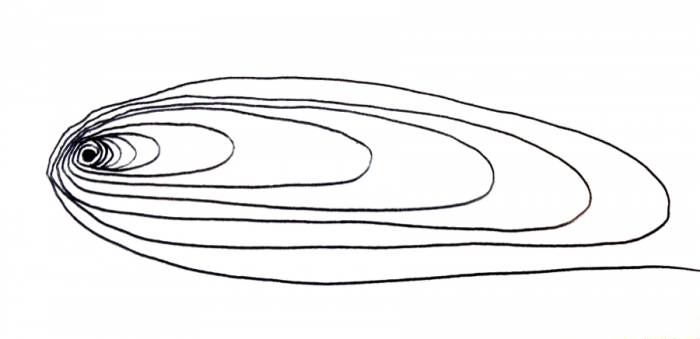

Healing is much more aptly described as an asymmetrical spiral.

I first learned about the spiral model of understanding healing when I trained to be a sexual assault survivor’s advocate at Earlham College. I’m not sure who originally came up with the idea, but I’ve heard healing described as a spiral by a number of counselors and sexual assault and intimate partner violence advocates over the years.

Whoever originally came up with the idea is brilliant, as their model describes so well what so many of us experience when we do the difficult but empowering work of healing from trauma.

This is roughly what the healing spiral looks like (excuse my crude drawing):

When we first begin to process being sexually assaulted, we are close to the trauma (pictured in the center of the spiral). Each moment or hour or day is filled with triggers that bring us back to our trauma.

But in time and as we begin to heal, we find ourselves spiraling further from the trauma. Does that mean we won’t ever have flashbacks or find ourselves close to the hurt again? No. We may be four years into our healing and we might feel that we’re far from what happened when seeing someone who looks like our attacker launches us into a panic attack.

(Side note: that’s why trigger warnings are so important – they help people avoid the things that will send them straight back to dealing with their trauma.)

The spiral model for understanding healing is an important departure from seeing healing as a spectrum, as it allows survivors to be gentle and loving with themselves no matter where they are in their healing.

The spectrum, on the other hand, often leads survivors to feel shamed (sometimes because we actually shame them) for being triggered when they are “supposed” to have been healed by now. A linear spectrum keeps survivors from seeking the help they need when they find themselves triggered when they’ve been working on healing for some time.__

No two people’s spirals look the same, just as no two people’s assaults affect them in the same way.

As such, the spiral model of healing is powerful because, again, it lets the survivor describe their trauma and their healing in their own terms while also giving them a way to name what their process moving forward can look like.

Knowing that it won’t always hurt quite as much as it does now, even if it will always be part of our lives, allows hope and empowers us to envision a life of survival, a life of coping and even healing.

Understanding that healing is a spiral empowers survivors with tools to advance their healing. And that’s crucial to imagining a survivor-centered logic when thinking and talking about sexual violence.

4. Embrace Survivor-Centered Logic

Yes, we need to abandon perpetrator logic. But that’s only step one. We have to establish a true alternative for thinking about sexual violence.

And if we ever hope to see an end to rape culture, that replacement has to be survivor-centered logic.

Simply put, survivor-centered logic:

• Trusts survivors to name their experiences and doesn’t attempt to name their trauma for them.

• Empowers survivors to heal on their own terms and through their own processes, even if we don’t fully understand why they need what they need.

• Believes survivors. False reports are incredibly rare and most survivors choose not to disclose or report publicly at all, so if someone says they’ve been sexually assaulted, the most important thing we can do is unequivocally believe them.

• Recognizes that any person can be a survivor of sexual violence, no matter their gender, sexual orientation, race, body size, class, or any other aspect of identity.

• Trusts survivors to know what’s best for them, even when it doesn’t seem best to us. Our healing is in our bodies, within ourselves; we just have to access it. Thus, we must trust survivors to know what they need to heal. If a coping skill seems unhealthy, perhaps try to help the survivor find ones that are healthier, but don’t tell them they shouldn’t rely on that coping skill.

• Helps survivors seek what they need to survive, heal, and thrive.

• Never blames the survivor in any, way, shape or form for their assault. Survivor-centered logic recognizes that one thing and one thing alone causes sexual violence: perpetrators.

***

Obviously there are countless other ways that we can center survivors in how we deal with sexual violence, but the point is that in mainstream, dominant society, we’ve been doing the opposite for far too long.

Thus, it’s time to leave behind perpetrator logic and to embrace survivor-centered logic.

What are some other ways that you could center survivors and support them in naming their experience and in healing?

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Minneapolis, MN. He lives with his loving partner and his funtastic dog. He blogs weekly at Change from Within. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more