I’ve often felt like I was “outside” of what it meant to be beautiful, yet uncomfortable whenever I’ve been told “you’re all so beautiful.”

The women I saw on TV or on the covers of magazines never really looked like me, and the times I did see Asian women featured in those media spaces, they didn’t look like me either.

It seemed like there was an ideal of beauty that I wasn’t quite living up to. I’m not petite and tiny nor tall and lean. My hair is frizzy and curly, not straight, sleek, and “silky.”

Celebrities and models featured in fashion magazines and beauty ads are mostly white women of a specific age and body type. Women of color selected to represent “beauty” tend to be lighter skinned and thin-figured, plus the media representations of women of color are often “whitewashed.”

There are constructed standards around what it “looks like” to be beautiful and attractive, and people are judged on how well they meet that standard. These judgments can influence job hiring processes, who people choose to be their friends, and how well someone gets treated by strangers.

In this way, beauty circulates as a form of capital and commodity with social, economic, and cultural value.

However, these standards are often measured along Eurocentric, white standards of beauty so narratives and ideals of beauty are heavily racialized.

Desired traits like a specific eye size, lip fullness, and nose width are premised on Anglicized standards. Recently, a beauty contest judged by AI machines using “objective” factors like facial symmetry ended up choosing mostly white winners.

Whiteness is simultaneously reinforced as norm while “otherness” gets fetishized and commoditized as “exotic.”

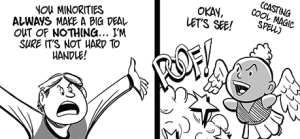

“I wish I could tan just like you do! Your hair is so thick, can I touch it? I love just how tiny you all are! What are you? Are you mixed?”

Our socially accepted beauty norms that idealize thinness, youth, and whiteness converge with the exotification of women of color.

For women of color, our bodies and sexualities are often turned into trends, jokes, and fetishes. These tropes also don’t allow room for multiple ways of looking and being.

I started to realize that my discomfort around my looks and my body exist because these images I saw every day didn’t allow room for multiple ways of looking and being. As women of color, we should be able to feel our own beauty on our own terms.

Having a sense of the historical, cultural, and political contexts of beauty norms allows us to begin unpacking and resisting the structures that make it so damn hard to just love ourselves, love our bodies, and love our looks just as they are.

Here are some ways that our beauty ideals reinforce racism.

1. Privileging Smaller Body Sizes and Sexualizing Different Body Types

Industries around beauty, fitness, and health converge with classism and racism in ways that select certain bodies as “lazy,” “sloppy,” and “unprofessional.”

What we think of as “normal” body sizes are actually thin idealizations of “smallness.” Bodies that seem in excess of the norm – that seems to get smaller and smaller – are under constant surveillance.

Historically, Saartjie Baartman, a woman born in southern Africa of the Khoisan people, was thought by Western publics to have a butt that was “unnaturally” large. While her body was similar to that of other women in her community, she was perceived as “abnormal.”

She was taken from her home and put on display, and after death, her body continues to be exhibited.

Today, the gawking at Black women’s bodies continues. For example, the size and shape of Serena Williams’ body is constantly scrutinized.

The false logic around biology, genetics, and race tend to also create unattainable fantasies around unrealistic proportions for a body, such as curvy bodies for Latina and Black women that are often associated with toned arms and small waists but big breasts and butt.

Julie Feng writes about this as the for/because clause – as women of color, our traits are considered as either exceptions or expectations of our race. We’re saturated in images that tell us that we need to work on our bodies to look a specific way.

Within a specific colonial imagination around “harem culture,” South and Southeast Asian women are exotified and sexualized as lithe and supple, thus flexible and eager to please. For East Asian women, norms of “smallness” translate to expectations of tiny, docile, doll-like bodies that become reduced and commodified as passive sex objects.

For women of color, perceptions of body types link to both objectification and hypersexualization.

I want to see changes in the expectations and boundaries of how my body is represented and recognized. We should be able to live under conditions where our many sizes, shapes, and sexualities aren’t scrutinized and surveilled.

2. The Obsession with (Non)Straight Hair

Last year, Allure magazine featured an article called, “You (Yes You) Can Have an Afro (Even If You Have Straight Hair).”

Beauty magazines like Allure cater to a predominantly white audience. While they rarely feature articles with tips for women of color, and specifically Black women, on how to style their hair, they’re in the business of teaching white women how to mimic the natural hair of Black women.

Maisha Z. Johnson traces how the objectification of Black bodies has been around in US culture since slavery and still manifests in everyday examples like preoccupation with wanting to touch Black women’s hair (and often this unwanted touching happens regardless of consent).

Despite this preoccupation, Black hair is still super invisible in mainstream media. Rarely are Black women depicted on TV or in movies with their natural hair – Black actresses and models are often shown with chemically straightened hair, wigs, or flat-ironed hair.

The norm of “straight” hair has also created an expensive, transnational market around the export and import of hair.

Because we only see images of Black women with straight hair, “natural hair” ends up seeming “unnatural,” becoming an object of curious interest.

We deserve bodily autonomy – and that includes not being ostracized or fetishized for things like our hair.

3. White(r) and Light(er) Skin

Skin bleaching is a $10 billion-a-year industry.

The internalization of colorism (the privileging of lighter and whiter skin across a hierarchy), shows up in different communities and cultures.

In different cultural and historical contexts, it’s way more complicated than people just merely wanting to “be like white people.”

In India, the diversity of skin color and tones creates a hierarchy of beauty with light-skinned people at the top and those with darker skin at the bottom. Across East Asia, practices of skin lightening may be tied to expressions of wealth and taste.

Whiter skin is a type of capital that indicates class status and also functions as a property value that allows people to gain access to concrete, material benefits that enhance quality of life.

Darker skin may signal a type of working class labor, whereas lighter skin indicates “upper class” status. Darker skin also gets marked in terms of morality – as more threatening and foreign.

For Black communities in the US, the historical context of slavery meant that whiteness indicated freedom and not being the object of someone else’s property. Today, darker skinned people experience heavier policing and state surveillance.

And on the flip side, the fetishization of flawless, dark skin works as an exaggerated overcorrection. For example, there was a lot of discussion over primarily white mainstream media coverage of Lupita Nyong’o that objectified her beauty after her performance in 12 Years a Slave.

Colorism also has its roots in imperialism and colonialism, where whiteness rules.

In the Philippines, Spain and the US forced a set of beliefs and values on Filipinos, imposing a “colonial mentality” where colonized people judge themselves and each other against white standards.

In contexts of colonialism and slavery, lighter skin also has a violent legacy of sexual assault by white men against women of color.

In the Latinx community, those with lighter skin may receive preferential treatment in state systems like education, labor, and politics, such as making more money, having higher employment rates, and living in neighborhoods with more resources.

The history is entwined with legacies of European conquest and colonization that created a complex racial hierarchy that now disenfranchises Indigenous folks and Afro-Latinx people.

These logics of white supremacy become embedded within communities and perpetuate the continued exclusion of those with darker skin.

These histories and ideologies have made it so we grow up feeling uncomfortable in our own skin – that makes us feel confused or isolated within and outside of our own communities. That’s not okay!

As we think about anti-racist and anti-imperialist work, that’s connected with the necessity of dismantling these classed and raced hierarchies around skin color within our communities.

4. Looking Young and Youthful

Beauty privileges youth – think about all the anti-aging product lines sold by the cosmetics industry or how models are mostly now in their late teens or early twenties.

This emphasis on “girlhood” as the peak of one’s beauty has a lot of creepy contexts, such as how young girls become sexualized from an early age.

Young girls and young women of color experience this sexualization within a racialized context. A quick Google search of “Asian girls” or “Black girls” primarily lead to results associated with pornography.

Yet, the interplay of racialization and age show up differently across communities of color and render young women vulnerable in multiple ways.

Asian women are often stereotyped as perpetually young and infantilized through tropes like the giggling “school girl.” The cutefication of our perceived “youth” is connected back to the tropes of Asian women being “tiny” and “small” – thus more submissive and easy to control.

In contrast, Black women are often falsely imagined to be older than they are.

In New York City, fifteen-year old Alexis Sumpter headed towards a summer internship was handcuffed by police for “looking too old” for her student metro card.

A couple years ago, Mikki Kendall and Jamie Nesbitt Golden started the conversation #FastTailedGirls to how stereotypes around Black women’s sexuality converge with the experiences of young Black girls growing up.

We should be allowed to grow up on our own terms – allowed our childhood, and also respect.

***

Because women of color look different than mainstream beauty ideals, our beauty is rarely seen on our own terms. People either tell us we’re “beautiful for a [insert your race here]” or they fixate on our skin color, hair texture, body shape, and other parts of our body.

Every day, we’re told that our bodies, our hair, our features need to look a certain way in order to be considered beautiful, and we spend money and time trying to achieve these unrealistic standards of beauty that are imposed upon us.

The insidiousness of white supremacy, imperialism, and capitalism bury themselves inside our own minds and tell us, you’re not pretty enough, you’re not skinny enough, you’re not light enough.

What kind of world do we live in that creates the conditions that loving ourselves unconditionally becomes a radical idea?

We deserve to be beautiful and to be loved on our own terms – not by a set of impossible standards measured on bodies and looks that don’t represent us.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more