Source: iStock

Girl power was the first form of solidarity I learned.

It made sense to me when I was younger, and it made sense before 9/11 – before I grew to understand that I would always be the “other.”

My coming of age story may not be like the ones that are portrayed by mainstream media portrays – and this seems to bother people. I wasn’t losing my virginity after prom or drinking in residence. I haven’t dated multiple people. I didn’t have a clubbing phase.

And that’s the way I wanted it.

I thought that was okay – and I thought that my friends, who liked me before we could do all of those things in our late teens and early twenties, would treat me the way they always had.

One thing that I did have in common with many of my during our coming of age was having a feminist awakening – but many of theirs didn’t seem to recognize my ways of being.

This became evident when my Muslim values started to be berated by fellow feminists.

Last December, my Muslim identity – an otheredness that will never change – became strikingly clear when my friend announced that her birthday wouldn’t be “my type of thing” because it involved alcohol. In the group chat where she mentioned it, it felt like I was suddenly a burden, an elephant in the room.

It didn’t matter that the summer before, I had gone to bars with my friends or that my one of our non-Muslim friends also didn’t drink. My “intersectional” feminist friend still felt compelled to make it clear that I was different, even though she knew I could come to the party without complaint.

The older I get, the more the once bright promise of solidarity appears to be a fading illusion.

Feminism, the supposed holy grail of acceptance, is the space in which I often feel the most rejected. And the microaggressions I experience in feminist spaces are an unexpected violence.

In my experience, I find that many feminists think that Muslim women hate themselves – but only because of loaded presumptions about our faith and how we practice it. Often, even supposedly “inclusive” feminist spaces reek of Islamophobic sentiment packaged as feminism.

Muslim women have been put into a subcategory – with our opinions and views silenced or used for political agendas without ever inviting us to the table.

And if I express that some feminists make me uncomfortable, I’m told that my existence makes other feminists feel uncomfortable.

In these instances, women who were the oppressed become the oppressor.

Apparently, it’s fine for me to be a feminist – as long as I avoid discussing how Islamophobic microaggressions are as common as table manners and how feminist events tend to be parties I’m not enthusiastically invited to.

But I can’t do that.

I can’t sit back and let feminists, who are supposed to respect and uplift other women, tell other, more marginalized women they’re “doing it wrong.”

And maybe those aren’t the exact words that they’re using. Maybe they don’t even realize that that’s what they’re suggesting.

But often, the women I seek solidarity with in feminist spaces and organizing end up telling me just that – that I’m not doing feminism right because I’m Muslim – in small ways that add up.

Here are five.

1. Sex Positivity to the Point of Shaming

Feminism is great for a variety of reasons – one of them being bodily autonomy.

This basic principle gets diluted and misconstrued, though, when sex positivity is thrown into the mix.

In many feminist spaces, whether virtual or physical, I encounter instances where sex positivity is a hot topic.

And it should be – because so many have been detrimentally harmed due to shame and stigma attached to sexually autonomous decisions.

But it starts to present a problem when the default expectation is that everyone who is feminist is sexually active.

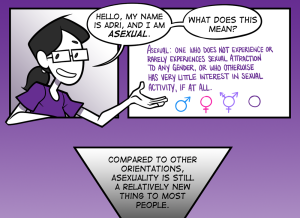

Women have traditionally been reprimanded for being sexual and taught to avoid all discussions of sexual being. The line between sex positivity and bodily autonomy gets blurred (or completely blown to bits), though, when it doesn’t encompass of a wide spectrum of what sexuality can look like, especially asexuality, and what positivity for that spectrum means.

Notions of sex positive feminism are in need of repair if the presumption is always that being sexually active means being liberated, while abstention from sexual activity means being oppression.

We don’t make decisions in a vacuum, and sex positivity will always look different to different individuals.

There’s an evasive presumption that Muslim women aren’t liberated if they’re not sexually active or public about sexuality. Not being sexually active – whether a decision based in religion or a sexual orientation, like asexuality – should be just as respected a form of bodily autonomy.

Some Muslim women have sex pre-maritally and some do not. And those are the nuances many miss.

There is also a complex history of Muslim women and sex where Muslim women are hypersexualized, but at the same time stripped of their sexuality. And this context is also needed.

Instead, Muslim feminists are either left out of sex-positivity conversation entirely or presumed to revere subservience to men.

At the same time, I’ve also found moments where Muslim women who are sexually active are also left out and treated as either deviant or “not actually Muslim,” while those who choose to withhold information about their sex lives are called “prude.”

Sex positivity doesn’t mean that everyone has to be talking about and having sex – and subsequently shaming anyone not doing either.

As feminists, we can all move forward with integrity if we also make room for the possibility that sexual liberation is found in abstention.

In enthusiastically choosing to engage in consensual sex, there is also an option to enthusiastically not engage for reasons based in beliefs. Conversations around sex positivity can replicate the harm of patriarchy when we isolate people in conversations for their autonomous choices and don’t make space for the wide variation in choices that exist.

2. Not Making Room for Different Priorities

My needs from feminist movements will differ from another person – and that’s because we’re all at different social locations.

And yet, this being seen as a negative (or otherwise difficult) is a recurring dynamic in mainstream feminist spaces.

For example, I may not necessarily want to fight for body hair positivity as much as some other women. I don’t shave regularly, and I’m really hairy.

But discussing that or posting photos of my armpits at their peak hair growth levels aren’t priorities for me, personally. And that’s cool if it’s a priority for some people, which is the beauty of feminism.

I have different concerns that I want to address in my feminist liberation first. My energy is channeled into fighting things related to my identity, like random selections at airports or Islamophobic violence in academia.

Everyone’s feminism is going to look different – and so will their priorities. You can also be passionate about multiple things at once and support a variety of movements.

But some causes more overtly impact embodiment. And because each individual experiences space differently, this can translate into the priorities each person spends their energy on.

I know that my feminist liberation isn’t going to come from celebrating body hair or posting pictures of my nipples.

But I do know that my liberation could stem from being respected as a Muslim woman. And that’s something that currently doesn’t always happen, including in feminist spaces.

For example, when I think about common causes in feminism like the body hair positive movement, I remember that the self-consciousness I have about my body hair is complex and rooted in comments white girls made about brown girls as a kid.

I have also witnessed the erasure of how many Sikh women have grown out hair related to faith, but not been championed as revolutionaries – but how many have been mocked by the same people now telling women of color to embrace our hair.

When a lack of nuance shows up in movements, it’s a disguised microaggression.

Our individual and communal complex histories impact all of us in feminist organizing. What draws each of us to a cause includes this history, but also includes what our immediate needs may be or where we may perceive our energies to be most valuable.

Supporting movements that impact women who are at different social locations than yourself is essential, but so is evaluating if the movement you participate in has considered intersecting identities in the first place.

Social movements are divergent and feed into the same fight against hegemonic structures that detrimentally impact us all, and the way we choose to fight them can be different. Supporting one another and bearing in mind the intersectionality of it all is vital in order to move forward collectively.

3. Feminist Events Being Alcohol-Centric

Drinking is a staple for many people – and having done some event planning, I realize that alcohol is a great pull for events.

I also know that some Muslims drink. And so I understand that when someone offers me a drink, it’s because there’s a possibility I might drink it. It’s out of goodwill.

The point where I get uncomfortable, though, is when I say “no, thank you” – which is a valid response to being given a drink – and it’s contested.

Soraya Roberts eloquently describes the awkward situations and social isolation that arise when she doesn’t drink in her essay “I Don’t Drink, Don’t Hold it Against Me.”

Like Soraya, I receive the typical assumptions that I must not like alcohol or that there must be a reason for not drinking. In fact, I don’t drink mainly because of beliefs that stem from my Muslim faith.

Events like Drunk Feminist Films or dance parties are places I tend to avoid – because when I have happily gone in support of my community, I’ve encountered a lot of discomfort from others about my autonomous decision not to drink.

On the equally awkward flipside, at times, in an attempt to seem culturally competent, some will simply alienate me when event planning.

I had a friend once who claimed she planned a whole separate birthday party without drinking so I would feel okay. I never asked for that – and I ended up going to her party at the bar anyway. I also didn’t need to be isolated as the corny non-drinker in a group chat.

To me, that’s passively violent – and definitely a way to signal that I’m the weird, uptight Muslim.

This almost insidious attempt at competency feels hollow – it’s a clear burden and favor I frankly never asked for.

In a deceptive ally attempt, it almost seems the awkwardness I should feel is somehow displaced onto them. The push to have meetings at pubs or going for drinks is fine – but just don’t get awkward if I get a water.

This isn’t an overt microaggression, but it can have the same ramifications as one. The social isolation and feeling of being “othered” due to not drinking, when attached to my Muslim identity, becomes a point of contention that seems to take a toll on people’s fun.

So, think of new ways to include non-drinkers in events. It’s super simple. For example, when events give attendees drink tickets, make sure they’re valid for non-alcoholic drinks, too!

Sometimes they’re not, and it leaves non-drinkers paying for drinks that are cheaper than the alcohol.

Worse, it leaves them feeling like the event was never intended for them in the first place.

4. Making Loaded Assumptions About Clothing

Not all Muslims wear the hijab, which is a head covering.

This seems simple, yet the minute the topic comes up, non-Muslims seem to have some interesting thoughts on how Muslim women dress, and how I don’t necessarily fall into their image of what a Muslim woman should look like.

Similarly, when I actively choose not to wear shorts, crop tops, or tube tops, further loaded assumptions are made about how I must be hindering my own liberation.

Recently, I saw a post written by an ex-Muslim go viral. The piece was about how a “man in the sky” dictates what Muslim women wear. The post made waves in anti-racist feminist circles.

And for me, what was apparent was the deeply rooted disdain that all of the women who shared and lauded the post must have for Muslim women who autonomously choose to dress in a certain way.

When non-Muslim women make choices about what they wear, we often view them as feminist choices. However, when Muslim women do, whether in hijab or not, leaps are made to explain why they dress the way they do – and the connection is made to socialization.

In reality, none of us live in a vacuum, and all of our choices will be affected by socialization.

Being concerned or making assumptions about how another woman dresses is potentially one of the least feminist acts that one can do – and yet, Muslim women are a popular target or this derision. These micro-interrogations can be draining and a waste of energy.

We all make our choices about clothing for different reasons – and the fascination with Muslim women is reproducing a discrimination that feminism should be trying to avoid.

5. Calling Me ‘Barely Muslim’ Because I’m Also a Feminist

Sometimes, I get to hear what I describe as a “compliment insult” – also known as a backhanded compliment. To prop me up, people will make a general insult about the Muslim community, assuming that it’s okay because my progressive beliefs unlink me to my Muslim faith.

In reality, any of the progressive beliefs that mainstream feminists value are, in fact, rooted in my Islamic faith. For instance, valuing every human life, equity along racial lines, and access to education are all Islamic values that my own feminism is built on.

Referring to me as “moderately Muslim” is assessing me like I’m a chicken wing – only moderately spicy. The levels of “Muslimness” that non-Muslims use to evaluate Muslims is troubling and places us on a spectrum we never agreed to.

“Moderately Muslim” or “barely Muslim” is a value statement typically said to me by people who seem shocked when I talk about faith and feminism.

The subtext typically implies a surprise that I could apply Islam to my feminist practice.

Some people even instantly dismiss me as a feminist because they believe that, as a Muslim, I “automatically support” the oppression of women: “So you’re a Muslim and a feminist? How does that work? Isn’t it an oxymoron?”

This erases a lot of the work that I do – and that of many other Muslim women over centuries.

The framework of our activism is anchored in Muslim feminism. To believe that Islam and feminism are not compatible is to erase tenets of Islamic faith that scholars like Amina Wadud have long illustrated are integral to Islamic practice.

Diversify the narratives that you share of Muslim women. Many non-Muslim feminists are drawn to a certain type of Muslim feminist narrative – one that is usually parroted by an ex-Muslim.

Although their experience is valid, it is just that – their experience. And there are many others.

***

At its core, feminism’s allure is equity – and understanding that older waves of feminism erased that is a first step. But, as a movement, feminists are still erasing Muslim women’s experiences. And we need a more inclusive feminist framework in place to rectify that.

And with Islamophobic sentiment rising in the West, it’s more important now than ever to support Muslim women in feminist spaces instead of paternalistically speaking for or erasing Muslim women from conversations entirely.

Muslim women want what other women want: the right to forge our own feminist futures.

Without accepting and supporting this right, we fail each other as feminists. By excluding Muslim feminists from larger feminist organizing is to replicate what patriarchy does to women. It is to strip Muslim feminists of their agency and voices.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Nashwa Khan is currently living and learning in the Greater Toronto Area. Her work has been published in a variety of places including New York Times Room for Debate, Vice, and National Post. She is currently in graduate school, attempting to balance it all. She is an avid storyteller and lover of narrative medicine and public health education, so feel free to tweet her about all of these things and more @nashwakay.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more