A black button reads “got privilege?” Credit: White Privilege Conference

I once published a piece about white privilege, and my white friend’s dad lost it. He read it and immediately called his son at work and asked him, “What are you doing right now?”

My friend replied, “Working, why?” My friend worked as a carpet cleaner, backbreaking labor for sure.

“Well, Jamie says you’re privileged. Do you feel privileged right now as you bust your a*s to feed your family?”

“Are you kidding me?!? Screw him! I’ve never had anything handed to me!”

And so the story goes.

How many times have you tried to discuss privilege with someone who is well-meaning but who has no sense of their own privilege and gotten a similar result?

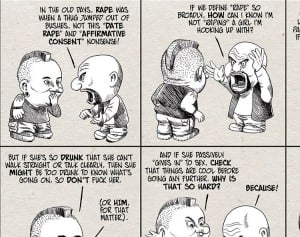

What is “identity privilege?”: Any unearned benefit or advantage one receives in society by nature of their identity. Examples of aspects of identity that can afford privilege: Race, Religion, Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, Class/Wealth, Ability, or Citizenship Status

After a while, my friend brought up my blog post that pissed off him and his dad so much, and we discussed it.

It didn’t go well. He immediately got defensive, and the conversation ended in anger.

As I reflected upon our talk, I took stock of some of the tools I have been given over the years from my diversity work to make this conversation more accessible and less hostile.

I decided to try again, so I reached out to my friend. The second conversation was tense at times, as any conversation about privilege can be.

But this time it went really well, and I think it did because I worked hard to change the tone of the conversation.

Afterward, I couldn’t help but think, “I need to share these tools!!!” Thus, whether you’re trying to talk male privilege with your dad, white privilege with someone on the bus, or right-handed privilege with your golfing buddy, here are a few things to consider before jumping into the conversation:

1. Start By Appealing To the Ways In Which They Don’t Have Privilege

One of the fastest ways to disarm a person’s defensiveness about their own privilege is to take some time to listen to the ways in which they legitimately do not have privilege and validate those frustrations.

I once attended a workshop with Peggy McIntosh, the original author of “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” The goal of the workshop was to give people tools for leading workshops of their own on privilege and oppression that get past the defensiveness.

One of her suggestions was to have people divide a paper in half. Have every person start on the left side of the paper and write down all of the ways in which they do not have identity privilege. They can include everything from being left handed and having to drag your hand through the ink to being a woman and having to deal with the gender wage gap. Then folks would write on the opposite side all of the ways in which their identity does afford them privilege that they did not earn.

From there, folks pair up and do a listening exercise where they listen intently to the other person talk about both sides of their list. Doing so allows people to air their frustrations at being denied privilege while also acknowledging that they do, indeed, have privilege.

From that place, it is a lot easier to help folks understand the power of privilege in creating a system of oppression and how eliminating that system is liberatory and transformative for everyone.

Now, to do this, you don’t need to turn it into a workshop. Just try asking the other person to talk about the ways in which they don’t have identity privilege and validate those hurts and frustrations.

Simply listening can go a long way! Plus, it’s a starting point for helping them build empathy for those who do not have their same privileges.

2. Stress That Privilege Is Relative

Each person experiences their privilege and lack thereof within the context of their own community and the people they interact with at the time.

As such, privilege is relative, and we need to talk about it that way.

Does that mean that all privileges are equal? No. I’m right handed and in turn, don’t have to drag my palm through the ink when I write. That’s a privilege I have by the nature of my birth.

That is not to say, though, that my right-handed privilege bears the same weight or social responsibility as the privilege that my skin color, gender, wealth, or sexual orientation afford me.

The point is that our identities are complex and intersectional.

Some folks get defensive about discussing privilege because they fear such a conversation will not address the real and powerful ways in which they do not have privilege. So they deflect by only talking about those things.

Just because we benefit from one form of privilege doesn’t mean that we benefit from all forms of privilege.

When we realize that, we can work together with people who share our privileges and those who don’t to build something better!

3. A System of Privilege and Oppression Hurts Us All

What we most need to stress in conversations about privilege is that this system doesn’t just hurt the people who cannot boast one form of identity privilege or another.

It hurts everyone. Until we understand that, we’re not getting anywhere because the only people of privilege who will ever act to end the system are the ones acting strictly from paternalistic guilt.

Take white privilege, for instance. White privilege is, essentially, a social construction whereby wealthy Europeans wanted to make sure that they could consolidate their wealth by pitting poor people from Europe against poor Africans and Indigenous people.

White folks were made to feel better about themselves and were given paltry privileges over people of color in order to divide the white proletariat.

All that meant, though, is that the white folks got to be the lords over people of color while the wealthy whites still had their boots on the necks of poor whites!

These privileges don’t help us as white people nearly as much as they hurt us!

Similarly, male privilege may benefit men tremendously in certain ways. But in others, it restricts us into a tiny box of masculinity. I don’t know about you, but I am sick of trying to fit into my gendered box, the “Act Like a Man” box.

I want my gender expression to be free and independent of those aspects of masculinity that hurt men and women – violence is acceptable for solving problems, boys don’t cry, men are the lords of their household, men must know everything even when they don’t, etc.

The privileges are marginal when we look at the system of justice that can be built on the other side of this struggle!

4. Privilege Does Not Have To Mean Guilt!

In The Construction of Masculinity, Michael Kaufman describes guilt like this: “Guilt is a profoundly conservative emotion and as such is not particularly useful for bringing about change. From a position of insecurity and guilt, people do not change or inspire others to change.”

So often, when introduced to the idea that they have privilege they did not earn, people respond in two ways that relate to guilt:

- Defensiveness: “I’m not going to feel guilty for what I inherited. If some people don’t have those same privileges, tough luck!”

- Paralyzing guilt: “This is just so unfair, but what am I supposed to do about it!? I never asked for this, and one little person can’t change a system that’s been around for hundreds of years!”

In both cases, we need to remind the person in question that feeling guilty doesn’t even need to enter the equation.

They’re right – they didn’t do anything to earn those privileges. So feeling guilty about them doesn’t make a lot of sense.

But a mentor of mine once said, “If we inherit injustice, we should never feel guilty. We are not responsible for that past. However, if we choose to do nothing about it going forward, then we have plenty to feel guilty about.”

Remind the person that they shouldn’t feel guilty for their privilege but encourage them to act to undermine the system by refusing to simply live in their unchecked privilege.

Which brings me to number 5…

5. Offer Concrete Ways That They Can Undermine the System of Privilege and Oppression In Their Own Life

When people are feeling paralyzed by or defensive about the revelation of privilege, it can sometimes help to offer them big and small ways that they can be subversive.

Encouraging action rather than stagnation can often bring people into the fold!

Throw out a few complex and simple ways for folks to “check” their privilege:

- If someone mentions an oppressive pattern that relates to privilege, i.e. “Men always dominate conversations and talk over women because they are taught that their voices are more valuable,” consider ways that you can choose not to participate in that pattern by, say, being aware of how often you’re speaking and stepping back to listen more often.

- Invest in accountable relationships across difference, not simple tokenizing relationships, and listen to those who do not share the same identity privilege about how this affects their life. Listening is the root of justice, after all.

- If some people are denied rights or privileges because of formal or state-sponsored oppression, refuse to participate in those oppressive systems. For example:

- If you’re straight, consider a commitment ceremony but don’t get married until all people can share in that legal right should they so choose.

- If you’re a white person with wealth and children, choose to invest in and send your children to a local, public, neighborhood school or at least a private school with a strong commitment to diversity and inclusion rather than a lily-white private place with connections to the Ivy League.

By encouraging action, you are not only helping the person in question a way to engage, but you are helping them understand the very nature of privilege and how it functions in a system of oppression.

6. Make It a Conversation of Actions, Not Character

Just as Jay Smooth says in “How to tell someone they sound racist,” the conversation about privilege should not be one about another person’s character.

The actual privileges we inherit because of our identity don’t define our character, but what does is whether we choose to act to change the system of oppression that affords us those privileges.

As such, the conversation should not be, “Hey, check your privilege, you privileged f*ck.”

Instead, it should be, “How can we work to check our privilege and undermine the system of oppression that hurts us all?”

When we focus on the actions we can take, the steps toward liberation we can take together, we make this conversation one that is not only accessible but far more powerful.

Do you have other suggestions for having these tough conversations about privilege and oppression? Leave them in the comments!

To learn more about different types of privilege, check out:

- White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

- 30+ Examples of Male Privilege

- 30+ Examples of Cisgender Privilege

- 30+ Examples of Heterosexual Privilege in the US

- 30+ Examples of Middle-to-Upper Class Privilege

- 30+ Examples of Christian Privilege

- 20+ Examples of Thin Privilege

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more