Source: CACophony

I have never seen an online petition started to get a white woman to comb her daughter’s hair.

If one exists and I’m unaware of it, link away in the comments. But the fact that the supposedly uncombed head of Beyoncé’s two-year-old daughter warranted a petition, however in jest, is just one example of the degree of scrutiny that comes with being black in public.

And I don’t mean Beyoncé public — I mean just anywhere within the line of sight of white people.

The office. At school. Within the military. There’s this unspoken pressure within the black community to present a “respectable” image of blackness at all times.

And the thing is, I get it.

In a society where the diversity of black culture is seldom represented in the media, where centuries-old stereotypes about being black refused to die with the minstrel shows, and people act surprised when a black person is “so articulate,” I get why people cling to respectability politics.

We want to be represented, we want to be valued, and we want to be seen as human.

And when we know that we as a race are being denigrated for whatever reason, we want to push back against that.

For those of us hung up on respectability, that means policing each other, sweeping some people under rugs, and putting others on pedestals.

Here’s why that’s bullshit.

Respectability politics — the notion that public blackness must be seen as non-threatening and commendable to outsiders — is more or less saying “My knowledge of who I am is less important than your idea of who I should be” to a dominant culture rooted in white supremacy.

Yes, I Said It: White Supremacy

I’m not talking about neo-Nazi white supremacy that’s hateful, deliberate, and in your face. I’m talking about the well-established form of white supremacy that often goes unmentioned.

White supremacy is the “ethnic” section of the hair aisle. It’s the “African-American” section of the bookstore that’s mostly romance novels for some reason. It’s the prison-industrial complex. It’s Angelina Jolie as Cleopatra.

It’s the fact that most of the wealth and power in the western world sits squarely in the hands of white people. It’s any part of society that treats white as the default and everything else as “other.”

White supremacy is a holdover from the days of colonialism and slavery, but it’s been largely upheld by people who either pretend it’s not there, consciously sustain it, or reinforce it to survive. Respectability politics falls in the latter category.

I don’t think anyone living at this point in time is to blame for the establishment of white supremacy as an institution. But people living in white dominant societies today are responsible for its continued existence if we don’t critically examine the ways it shows up in our lives.

How Respectability Politics Play Out

In this article at Feministing, Sesali Bowen writes about the way Maya Angelou’s words and legacy have been used by some to attack the open sexuality of black women like Rihanna, despite the fact that Maya Angelou wrote about her own experiences doing sex work without couching them in shame.

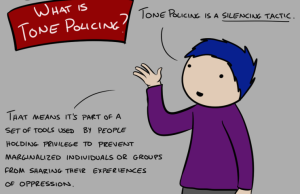

This is what respectability politics looks like — painting people as this or that, saint or sinner, poet or Jezebel instead of recognizing them as fully human.

And it’s weird, because that’s pretty much how all those stereotypes about black people that have endured since slavery portray us — as all-or-nothing caricatures instead of multi-faceted human beings.

We want role models, yes. We want to see people who look like us being recognized and honored, yes. But at no point should we be idealizing and idolizing certain black people as exemplars of respectability while denigrating others.

If you believe black poets and scholars and activists should be recognized for their accomplishments, then recognize them — all of them. Get to know the full lives of public black intellectuals that the media has attempted to whitewash over the years.

You can also recognize the people that the words and actions of those intellectuals benefitted — black people who may or may not give a damn about how transparent their clothes are, who may wear their hair straight or kinky, code switch or keep their accents. Because if you’re only looking to elevate some black people based on the gaze of some white people, you’re not really here for any of us.

Seeing Ourselves through Our Own Eyes

I’ve been using “we” throughout this article because internalized racism — and its close friend, respectability politics — is something that many black people in white dominant cultures live with.

Internalized racism is absorbing the message that people of color are less than or less capable than people who are white, and it’s the kind of thing that can hide in the shadowy corners of the mind for years.

Internalized racism leads to a self-conscious state of being, a lingering comparison between one’s self and what’s touted as “normal” or “good” (read: white) by society.

This isn’t necessarily some heart-wrenching internal battle that makes itself obvious. Like straight up racism, internalized racism is subtle and most people who live with it don’t recognize it for what it is.

So internalized racism sneaks its way into attitudes and conversations where it goes unchecked and unnoticed. I’ve heard many words come out of the mouths of black people about black people to black people that were variations of “the closer to white you are, the better.”

And I don’t mean that to say that internalized racism is the same thing as a desire to be white.

It’s more like looking at yourself from an outsider’s perspective, seeing your own skin as different or your own culture as other, and judging people of your own race by the standards of another.

Internalized racism is well-meaning parents who push their children to learn “proper” English or shave off their locs for job interviews — because it’s easier for us to adjust ourselves than it has ever been for society to adjust to us.

The problem with respectability politics is that it implies that by striving after the respect of white people, black people can work hard and overcome structural barriers to social mobility. But it doesn’t work that way.

It brings to mind the oft repeated adage “We have to work twice as hard to get half as far.”

And yeah, while things are the way they are, people will do twice the work just to survive. But are we going to sit here watching each other to make sure we’re doing enough, or are we going to ask why it’s 2014 and we’re still working this hard?

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Want to discuss this further? Visit our online forum and start a post!

Jarune Uwujaren is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. A Nigerian-American recent graduate who’s stumbling towards a career in writing, Jarune can currently be found drifting around the DC metro area with a phone or a laptop nearby. When not writing for fun or profit, Jarune enjoys food, fresh air, good books, drawing, poetry, and sci-fi. Read their articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more