Source: lei21eme

If you’re a longtime reader of Everyday Feminism, you may have noticed that we talk about race a lot. Maybe you’ve wondered, “Why do they do that?” Or maybe even, “Why do they seem to hate white women?”

For the record, we don’t hate white women any more than feminists hate men. Which is to say, we don’t hate white women at all. We just want to be intersectional, which means acknowledging that white women have white privilege.

See, the thing is, gender doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It intersects with other social identities, including – but not limited to – race. Therefore, even if a white woman faces oppression because of her gender, she can still benefit from privilege because of her race.

What does this privilege look like? One example is the insistence on changing #BlackLivesMatter to #AllLivesMatter.

It’s important to acknowledge white women’s privilege because if we don’t, we’re ignoring the ways in which it can hurt women of color. In addition, we can’t begin to address the experiences of all women until we acknowledge race.

If a white woman is oppressed because of her gender, but benefits from privilege because of her race, then conversely a woman of color is oppressed because of her gender and her race.

Therefore, what might be empowering for white women might not be so for women of color. It might even be harmful to them.

That’s why anti-racism work isn’t separate from feminist work, but is actually a crucial component to it: When the ways in which we’re oppressed intersect, we can’t truly dismantle oppression until we consider more than gender in our feminism.

In order to make this point clearer, I’ll give three examples of feminist issues which require us to dismantle racism in addition to sexism.

1. Income Inequality

This one’s relatively simple to break down.

When people talk about the wage gap between women and men, they’re usually talking about white women and men. When you factor race into the statistics, things get more complicated.

According to the Census Bureau, white women make 78% of what white men make. However, women of color make less than that. Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women make 65%, Black women 64%, American Indian and Alaska Native women 59%, and Latinx women 54%.

What’s more, although all women make less than their male counterparts within each racial group, white women make more than Black and Latinx men.

Not all men make the same income either. The employment gap between Black men and white men is attributed to hiring discrimination, high incarceration rates for black people, and Black Americans’ lack of generational wealth due to a long history of discrimination.

These facts may also explain why Black women are graduating high school, attending college, participating in the labor force, and starting businesses at higher rates, yet still aren’t making as much as white women.

What all these statistics prove is that there’s more at play in income inequality than just gender. So if we’re going to eliminate the wage gap for more than just white women, then we have to undo the racism that prevents people of color – and women of color in particular – from getting equitable pay.

2. Sex-Positivity

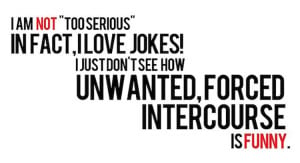

(Trigger Warning: This section discusses sexual violence.)

As I understand it, sex-positivity is about empowering women to take control of their sexuality. That can be a good thing, but as Everyday Feminism has already discussed, there are a few reasons why sex-positivity without critical analysis is harmful.

I want to contribute to that discussion by talking about how race complicates sex-positivity. Specifically, I want to talk about why we can’t declare that sex is empowering for everyone until we examine how sexual violence has historically and contemporarily been used to oppress women of color.

All women are subject to sexual violence. But for women of color, sexual violence is often used as a tool by the state in order to oppress them. In the following paragraphs, I’ll discuss the way in which it’s been used against Asian women in particular.

A quick Google search will tell you that rape as a weapon of war isn’t an anomaly. What’s more, it’s commonly sanctioned by policy. For example, Arlene Eisen has written in Women of Viet Nam that during the Vietnam War, US soldiers would receive instructions to rape Vietnamese women.

This state-sanctioned sexual violence extends to Asian women in America as well. Our mothers, grandmothers, and other female relatives have been affected by that violence. And in an even more direct way, the fetishization of Asian women as submissive and willing comes directly from the US military presence in Asia.

Therefore, as an Asian American woman, I feel uneasy with the claim that simply enjoying sex will empower me. First of all, it’s not easy to enjoy sex when you have to work through the trauma associated with it as an Asian woman.

Second of all, the very act of sex itself when one is an Asian American woman has become fetishized through violence. Being fetishized isn’t empowering in the least.

I’m not saying that women of color shouldn’t have sex or shouldn’t enjoy it. Cate of BattyMamzelle has talked about the problem of framing Black women’s sexuality from the perspective of the male gaze. She argues that doing so erases Black women’s sexual agency.

I totally agree with that, and by the same token, I also believe that Asian American women should reclaim their sexual agency. In fact, I think it’s important to do so because of the ways in which sexual violence has been used to oppress us.

Of course, all women are subject to sexual violence, and sexual violence is used to dehumanize all of us. But as the National Alliance to End Sexual Violence aptly put it, racist stereotypes about women of color – which arise from a history of state-sanctioned violence – help perpetuate and legitimize our sexual abuse.

So am I against sex-positivity? Not exactly. I think that making sex empowering for women is a good thing.

I just think that making sex empowering for women of color is a complicated matter because of the specific ways in which sexual violence has been used against us.

In other words, making sure sex is empowering for women of color means examining how racism is complicit in making it disempowering for us in the first place.

3. Beauty Standards

Campaigns like Verizon’s “Inspire Her Mind” encourage us to focus on things other than women’s beauty. They tell us that we should value things like intellect, not just looks.

This isn’t a bad thing. Obviously, we shouldn’t make a woman’s beauty the end-all and be-all of her worth. But not all women are considered equally beautiful, and we can’t tell women to simply ignore beauty if they’ve been hurt and humiliated for their lack of beauty all their life.

Whether we like it or not, beauty standards are a powerful force in our everyday lives – and they’re based on white women. White women – and, more specifically, thin white women – dominate media images, from billboards to TV shows to movies. Most icons of beauty are white women.

You might say, “That’s not a good thing! These women’s beauty supersedes any other qualities they might have, and that’s oppressive.” And it is. I won’t argue with that.

But the thing is, because white women are already considered beautiful, it’s easy to say that beauty standards must be shed. Beauty doesn’t have to take precedence for white women. It’s a quality that’s already been assigned to them, however negative the consequences may be.

That’s not to say that white women aren’t made to feel ugly. It’s just that beauty standards are based on whiteness, so women of color have another (sometimes impossible) hurdle put in their way to being considered beautiful.

Imagine what it’s like seeing these beauty standards and knowing that you’ll never fit them because of your race. You could lose weight, wear makeup, and buy pretty clothes, but no matter what you do, you won’t be considered beautiful because you’re not white.

What I’m trying to demonstrate is that for women of color, their race and gender intersect in beauty standards. As women, their beauty is under scrutiny. But as women of color, that beauty is found lacking. In other words, they’re not beautiful because they’re people of color.

All women know what it’s like to be denigrated because they aren’t considered beautiful. But here’s the thing: People of color are dehumanized for the way they look. It’s even worse for women of color, because a woman’s value is often measured by her looks.

If you’re not convinced, consider how scientific racism classified physical features in order to prove the inferiority of people of color. Scientific racism has long been debunked, but believe it or not, there are still those who use women of color’s physical features to dehumanize them.

Therefore, racist remarks about how people of color look (think: stereotypes about Asian people’s “flat” faces and “slanted” eyes) aren’t somehow unrelated to scientific racism and the idea that people of color’s physical features are inferior. They’re probably rooted in them.

And that’s not just insulting. It’s damaging, especially for women.

That’s why I find it problematic when white feminists urge women to ignore beauty standards. How does that help women of color, when we have no chance of fitting into those beauty standards in the first place and are devalued for it?

In fact, for women of color, being beautiful and celebrating it can be empowering. It’s a way to push back against the ways in which we’ve been oppressed.

So if we’re really going to begin dismantling beauty standards and their harmful effects, we also need to get rid of the racism that informs them.

***

There are many more examples that I could give, but the bottom line is that women of color don’t have the same experiences that white women do. Their experiences are informed by their race, and that’s why anti-racism is necessary to feminism – in tandem with anti-sexism.

Talking about race and white privilege doesn’t mean hating white women or claiming that they don’t face oppression. It means that we’re considering the extremely diverse experiences and needs that women have, so that we can effectively dismantle all systems of oppression that uphold them.

It means that we’re doing our best to make sure that all women are empowered, and, more importantly, treated humanely – which is, after all, the goal of feminism.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Kerry Truong is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. They are a queer diasporic Vietnamese womxn and graduated this spring with a double degree in English and Asian American Studies. When they’re not philosophizing about this at length, they’re reading, taking long walks, or cooing over all the dogs who cross their path. Read their Everyday Feminism articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32