Source: Mobiles 24

Dear Partner,

You probably didn’t think that the text you sent last night about your Crossfit personal record might be a problem. You also probably had no idea that I’d spend hours dwelling on the offhand comment you made about eating too many calories at lunch. And it might not have occurred to you that telling me I’m perfect as I am when I’m feeling less-than-perfect might not be as constructive as you thought it was.

Dear partner, I understand that you don’t understand what it’s like to have an eating disorder, and I want you to know that I know you’re not trying to trigger me. But if you really want this relationship to work, we’re going to need to talk about my eating disorder recovery.

Here’s the thing: Recovering from an eating disorder is hard enough when you have your own inner voice constantly making jabs at your appearance or the media/marketing machine screaming about your imperfections across every screen and airwave, let alone when you open up and share your body with another human being.

As a recovered anorexic, and one who is often triggered by sex and relationships, I’ve avoided dating because my fear of being triggered (or my reactions when I am) makes me feel guilty for potentially inconveniencing my potential partners.

But I realize that it does take two to tango – and I also understand that dating someone who has had an eating disorder and not wanting to cause harm can also be terribly stressful for the other partner in the relationship.

Therefore, it’s incredibly important for both of us – as partners – to be able to communicate about the elephant in the room.

It’s my job to disclose that I’m in recovery in order to keep you from making the unintended mistake of triggering me, and it’s yours to be compassionate, aware, and willing not to be a trigger.

In the spirit of full disclosure and communication, here are a few ways to be a “recovery ally.”

1. Recognize That an Eating Disorder Is a Mental Illness

No one chooses schizophrenia. We’re sensitive to PTSD. We understand that depression is a medical condition.

So why is it that eating disorders are dismissed as “attention seeking” or trivialized by appropriating the word “anorexic” to describe thin movie stars or “binge” to describe eating one extra cookie for dessert?

Eating disorders are mental illnesses, and some of the depressive, anxiety-ridden, or obsessive thoughts or behaviors may persist even after recovery.

As a partner, you need to be prepared for rough days.

That means offering both space an support – and not judgment or unsolicited advice. Comments like “What’s the big deal? You look great” or “Why don’t you just try eating [insert fear food here]. It’s not that serious” don’t help. If anything, it just makes your partner feel worse because they can’t access your state of good-natured apathy toward the situations that, to their disordered brain, sometimes feel like actual crises.

Treating an eating disorder like a laughing matter or using dismissive language is troubling and triggering. You wouldn’t tell someone with bipolar disorder that they should get over it or chill out (and if you would, you shouldn’t).

Treat your recovered or recovering partner the same: Honor the illness for what it is, offer what support you can (and advice only when asked for it), and give them time to feel the feelings.

In recovery, your partner will hopefully have learned coping skills and/or developed a support system. Leave the advice to the professionals and, as an intimate partner, just be a shoulder to cry on. This, too, shall pass. (And if it doesn’t pass, then please gently remind your partner to call a therapist or qualified professional for help.)

2. Change Your Language

Changing your language and your lifestyle in order to be someone’s partner is an inconvenience – true. But if you’re a heavy drinker, and you make the choice to date a recovered alcoholic, you learn to stop suggesting dates at the wine bar.

So it stands to reason that you must treat your relationship with someone who is recovering from an eating disorder in the same way.

Contrary to what the media would have you believe, feeling good in your body and solid in your nutrition and exercise is not predicated on talking about food and fitness all day.

Yet our first-world culture is obsessed with talking about body image, weight, workouts, and what we ate on Wednesday. I challenge you to find one office kitchen in the United States in which coworkers don’t spend their lunch hours commiserating over the last five pounds while eating stale cookies from yesterday’s meeting.

Weight and food are, like the weather, easy targets for starting cocktail party conversations – because everyone has to eat. Moreover, we build entire tribes and identities based on our diets and workouts.

That said, it doesn’t get you off the hook if your partner has disclosed an eating disorder to you.

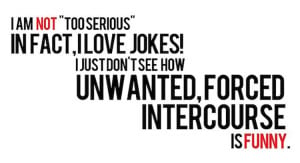

Think about it this way: Casually talking about your diet, your weight, or your workouts can be as triggering to an eating disordered partner as casually telling a rape joke in front of a partner who has been raped or sexually assaulted (and I’m going to make the bold assumption that you’re not the kind of person who thinks it’s a good idea to casually make rape jokes in the first place).

If you’re willing to be supportive of your partner’s recovery, then that means you are willing to be sensitive about the language you use around them.

There’s nothing wrong about wanting to share your excitement about doing something that makes you feel great with your partner, like starting a gluten-free diet or training for an obstacle race. However, you can learn to express your excitement by channeling that energy into something you can do together, like a movie night or a trip to a karaoke bar.

If that doesn’t seem like something you can do – because you enjoy talking incessantly about why you’re cutting out gluten/sugar/meat/whatever, about how you need to lose the holiday weight, about your max lifts and your fastest times – then you and your partner might need to have a conversation about ending the relationship.

In other words: If you require nightly trips to the pub where everybody knows your name, don’t date someone who is working the twelve steps.

3. Don’t Be the Food Police

There is a fine line between having your partner’s best interests in mind and playing the food police.

Counting the number of cookies left in the jar when you live with a binge-eater or shooting disapproving looks at a former anorexic who hasn’t finished her meal can be more damaging than helpful.

Eating disorders thrive when they’re fed with guilt and shame – guilt for taking part in bad behaviors and shame for being bad.

Even after recovery, when a formerly eating disordered person is put back into situations where they’re made to feel guilty for eating too much or too little (even if that’s not your intention), they may then also internalize that guilt and feel ashamed for not being good enough to fully overcome the disordered behaviors – and furthermore, to be a “less complicated” partner for you.

Guilt and shame about food may drive your partner to feel like they need to hide the behaviors from you – and eating disorders multiply in the darkness.

To avoid this, keep your observations to yourself. Obviously, if you see serious and repeated self-harming behaviors that require intervention, that’s a different story, and you can reach out to family members or qualified professionals who can assist in the case of a relapse.

But for day-to-day food weirdness, it’s not your job to decide how many cookies do or do not get eaten.

The recovered individual gets to find his or her own path and learn how to become comfortable eating around others, one strange meal at a time.

4. Stop Telling Me I’m Beautiful

There is nothing worse than hearing “You’re beautiful exactly as you are” in the moment when you’re hating yourself exactly as you are.

If the thing that your partner loathes is beautiful to you, their inner dialogues may state, then it’s clear that you are not meant to be partners and that you have terrible judgment.

Of course, recovering persons can’t expect their partners to fix them, so there’s obviously an obligation on their part not to put themselves in a potentially dangerous situation by jumping into a relationship before they’ve started working on self-love.

That said, there is a certain responsibility on the part of a partner to reduce the potential for harm, and that includes moving the focus of conversation away from the body.

Telling your partner that you love their curves, for example, might be triggering, because they are still coming to terms with having to have curves in the first place. Just because you love those curves doesn’t mean they do, and hearing that they have them may trip the “self-harm” alarm in their head.

It can feel really wonderful to compliment your partner on their progress, whether it’s gaining weight and overcoming underfeeding, losing weight and overcoming binge eating, or just simply having a body that turns you on. But try to channel some of that positive energy into complimenting them on a non-scale victory.

There are plenty of ways to show your partner that you support the incredible person they are. Try to find one that isn’t body-specific in order to reduce potential and unintended triggers.

5. Understand That Sex Can Be a Touchy (or, in This Case, No Touchy) Subject

Eating disorders, contrary to media portrayal, are rarely about becoming thin to be “sexy.”

As I mentioned earlier, they are a mental illness, and the disorder – whether it’s restriction of food or the bingeing or purging of it – is about trying to soothe underlying anxiety or obsessive compulsion by controlling the body.

In many instances, the disordered person develops the obsessive desire to simply disappear. Any reminder that the body is tangible – including touch by someone they love – can be a painful reminder that they have failed to meet that objective.

The inexplicable repulsion to or fear of touch, even into recovery, can hinder sexual exploration (even though they may feel desire and want to participate in sexual activity with their partners).

Eating disorders are also sex drive killers.

Everything from depression and anxiety to hormonal dysregulation can stop the “hot and heavy” in its tracks. These effects can last long after recovery – which can be very frustrating to a partner with a mismatched drive.

This doesn’t make your partner frigid or withholding; however, it does require a little bit of understanding on the days (or weeks!) when they are not in the mood to be turned on. (This could be a good time, however, for some consensual cuddling or reassuring hugs.)

Moreover, it has been estimated that around 30% of those who develop eating disorders have been sexually abused.

Sexual abuse alone is often a hindrance in the development of mature sexual relationships later in life; when coupled with the trauma of an eating disorder, it can provide a serious challenge to both partners.

Hopefully, your recovering partner will be working through the trauma with a licensed professional or through other means, but please understand that this is a long and difficult process.

If you truly love and support your partner – and want to remain a partner for the long haul – you may have to develop and exercise a good amount of patience and restraint.

Encourage an open, honest, and non-judgmental conversation about consent, expectations, and desire. Take it slow. And do not push. Understand that your recovering partner wants to be with you just as much as you do, but your partner’s expression of that desire will take its own form and develop over time.

***

So, as my partner, what can you say or do?

Don’t make assumptions about what we can and can’t talk about.

Just because you had a friend who had an eating disorder or read an article about body positivity doesn’t mean that it applies to me.

While it’s my job to disclose that I have disordered eating, it’s your job to find out what that means and how I’d like to talk about it.

If you’re not sure where the boundaries are, then ask. Set the precedent for respect and openness. Admit that you don’t know what it’s like to have my problem (and I’ll take care of the admitting when I feel like the problem is getting in the way of my life).

It is fully possible to recover from an eating disorder and to carry on a normal relationship, but because of the presence of behaviors associated with this mental illness, our partnership will require a different level of love, understanding, patience, and openness.

If you’re ready and willing to be my partner, then let’s have a conversation about my eating disorder recovery – so we can start talking about the rest of our lives.

Sincerely,

Me

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Kaila Prins is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a health coach who works with women who are ready to stop “recovering” from disordered eating and start “discovering” their true identities. Kaila’s health coaching services, as well as her blog, can be found at In My Skinny Genes, and she hosts a weekly podcast called Finding Our Hunger. She also counts characters and not calories on Twitter @performingwoman.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32