(Content Warning: Sexual violence)

Originally published on Role Reboot and republished here with their permission.

In 2014, an Englishman was sentenced to five years in jail for raping a woman while she slept. As the judge put it, “She was a pretty girl who you fancied. You simply could not resist. You had sex with her.” He went on to assure the man, “I do not regard you as a classic rapist.”

The good old “classic rapist,” such a comfort to ignorant judges, untold numbers of campus administrators, and polite society everywhere. Also particularly useful to predatory rapists who continue to act with impunity in the face of myth-making judges.

This kind of language enables future rapes and makes us complicit.

Its use should disqualify jurists, who, at the very least, should be trained in facts before being allowed to sit on benches.

The “classic rapist” is a popular rape myth, like many others involving dark alleys, dark men, bad women, good women, light women, violence, and more.

The “classic rapist” is a blunt force example that is easily disproved, since we know in the vast majority of reported rapes the parties know one another – 73% are “non-strangers,” and 38% are friends or acquaintances.

Most of the time, however, the delivery is more subtle and euphemistic.

Consider:

- “Had his way with her”

- “Forced himself on her”

- “Inappropriate behavior”

- “Offensive behavior”

- “Indecent assault”

- “Carnal knowledge”

- “Domestic dispute”

- “Family matter”

- “Defiled her”

- “Sexual misconduct”

- “Unpleasantness”

- And, my all time personal favorite: “took liberties.”

Sadly, this judge is not alone.

His language and ideas are those of our traditions and popular culture, including the media – the place where words most shape our perceptions and understanding of the world.

In the media, there are so many common phrases that convey the everyday sexism of trivializing and hiding rape:

- “Bad sexual etiquette”

- “Forced to perform oral sex”

- “A circumstance”

- “The subject matter”

- “Bad hookup”

- “A crime of personal injury”

- “Assaulted while unconscious”

- “Inappropriate behavior”

- “Sexual impropriety”

- “Sex allegations”

- “Child bride”

- “Forced to marry”

- “Sex with a child”

- “Sexual activity deemed…to have lacked consent”

- “Forced her to engage in sex acts”

- “Seduced the child”

- The child “seduced him”

- “Taken advantage of”

- “Incestuous relationship”

- “Toddler sex case”

- “Theft of services”

- “Sex Scandal”

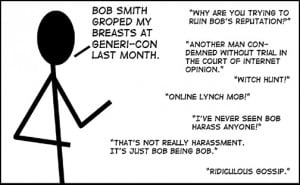

All of this happens in an environment where rape is used as a metaphor, is a trending joke theme, and where a judge can ban the use of word “rape” (or “sexual assault”) in a rape trial.

In an effort to end rape doublespeak, the founders of the website Ending Victimization and Blame (EVB) analyze media to explain how language like this, which, as they put it, succinctly “panders to the belief that men are unable to control themselves.”

It is, as Melissa McEwan has also so assiduously detailed for years, all part of the weave and weft of institutionalized rape culture.

“Our campaign challenges victim blaming language which focuses on the victim rather than the perpetrator,” explains one of the anonymous founders of EVB. “Such as discussions of rape that focus on women dressing ‘appropriately’ rather than on the perpetrator’s choice to commit rape. We also challenge language like child sex, child pornography, and child prostitution, which imply that children can consent to their abuse.”

Consent, a recent and revolutionary idea, is a bitter pill for some people, apparently also in courtrooms.

Courtrooms are where we’d like to think rape myths and sloppy, unhelpful language go to die, but that’s frequently not the case. Instead, in courtrooms, or on college campus adjudication boards, survivors frequently feel instead that they are revictimized or the ones being investigated.

We are subjected to a steady stream of news about judges who clearly hold seriously outdated and biased ideas about sex, gender, violence, and rape.

Judges who call 13-year-olds sexual predators who “target” 41-year-old abusers. Judges who, in order to excuse the behavior of adult men, grapple to pinpoint that elusive moment when a girl child becomes a scheming woman who is fair game for rapists.

Although, some don’t even disguise their efforts, such as the lawyer in Texas I can’t get out of my head, who compared an 11-year old gang-raped by almost two dozen men to a “spider” that “lured” them into her dangerous sexual web.

It also isn’t limited to children.

Case in point, the Arizona judge who told a woman sexually assaulted by an off-duty police officer in a bar, “If you wouldn’t have been there that night, none of this would have happened to you.” So much “unpleasantness.”

Language plays a significant part in this process of inversion of shame, responsibility, and guilt.

Susan Ehrlich, in her linguistic analyses of the language of rape, consent, and the law, used the term the “grammar of nonagency” to describe how language works in favor of perpetrators.

Of course, given the very small percentage of rape cases that actually make it to courtrooms, it’s clear that the attitudes, myths, and language issues start much earlier in the justice pipeline.

FBI and crime experts estimate that anywhere from 60% to 80% of rapes are never reported to the police and, of those reported, huge numbers are undercounted and miscategorized by officers who exhibit overt and implicit bias and incorporate rape myths into their assessments. In the past 18 years, the conservative estimate for missing reported rapes is more than one million.

While I’ve been unable to find comparable studies for judges, a majority of police detectives with fewer than eight years of experience with sex crimes think that 40% of claims made by survivors are false (in some places, that number is 80%).

However, once officers have spent more than eight years working on these issues, that number drops to 10%, and the acceptance of rape myths is significantly lower. (Rates of false allegations of rape are well understood by criminologists and other social scientists as between 2% and 8%). There is no reason to think that judges are immune to the implicit biases or acceptance of rape myths.

Every time you hear or say these types of expressions, the question should be “Who benefits from not saying ‘rape?’” Who is helped when we refuse to be accurate about rape?

Because it’s certainly not rape victims.

Most rapists in the world operate unchallenged and are rarely punished and they do so because we make them comfortable by misrepresenting the crimes they perpetrate, and language like this is one of the ways we do it. Current estimates are that only 3% of rapists ever see jail.

When feminists say “rape is rape – use the accurate word,” it’s because specificity helps us understand and confront the problem. It’s not because we delight in making people uncomfortable, but because we understand how complicit language and notions of rape are in defining rights in society.

Writing in her landmark study, Redefining Rape, Estelle Freedman explains that the way we define rape informs rights, reinforces economic inequalities, and sustains discriminatory practices in the law and society. Rape narratives in America have, as she so ably demonstrates, everything to do with social hierarchy and power.

I’m not suggesting it’s easy to talk about rape openly—at home, in schools, in places of worship. It’s hard. It’s unpleasant. Not everyone can talk about rape at the dinner table. But using correct language and destigmatizing rape victims means confronting, instead of perpetuating, the problem.

It’s really important and, in the end, makes people, especially children and young adults safer: 44% of reported rapes include survivors under the age of 18, and 80% are under 30.

The Chicago Task on Violence Against Girls and Young Women has published useful language guidelines in Reporting on Rape and Sexual Violence, a media tool that should be required reading for writers, editors, and headline writers. It wouldn’t hurt if it were required reading for lawyers and judges either. Granted, it’s not a light summer read, but neither is having to see “You’re not a classic rapist” pop up on your newsfeed.

As long as we live in global culture where shame is assigned to the raped and not the rapists, the only people allowed to use euphemisms should be survivors.

Writing last year, Bishop Desmond Tutu, Jacob Lief, and Sohaila Abdulali explained, “Rape is utterly commonplace in all our cultures. It is part of the fabric of everyday life, yet we all act as if it’s something shocking and extraordinary whenever it hits the headlines. We remain silent, and so we condone it.”

And, when we aren’t silent, we use euphemisms, which are worse than silence, because they trivialize and mythologize it.

There’s a high chance that my inbox will be populated by “stop word policing” messages as a result of this piece.

l’ll stop talking about reality-shaping words when clearing through our national backlog of more than 400,000 rape kits is a priority for society and the annual tally of rape doesn’t result in the undercounting of more than one million rapes.

Changing words to #EndRapeDoubleSpeak is a good way to start.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Soraya L. Chemaly writes about gender, feminism and culture for several online media including Role Reboot, The Huffington Post, Fem2.0, RHReality Check, BitchFlicks, and Alternet among others. She is particularly interested in how systems of bias and oppression are transmitted to children through entertainment, media and religious cultures. She holds a History degree from Georgetown University, where she founded that schools first feminist undergraduate journal, and studied post-grad at Radcliffe College.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more