As an Asian American, “Where are you from?” is a question that comes up often.

When meeting people for the first time, conversations often drift towards questions like, “When did you move to New York City? Where did you move here from?”

Those questions are fine. I might talk about the town that I grew up in, the city where I went to college, the city where I worked my first full-time job, the places I lived in-between.

Yet. Despite those answers, I’m often asked, “But, where are you really from?” or “Where are you from from?”

It’s the “really” or the “from from” that frustrates me. Because, from what I’m understanding, the question is actually: “You don’t seem like you belong here, so where are you really from?”

But what if someone’s just being curious – you might ask. Sure, it’s okay to be curious, but think about what you’re asking or what you’re curious about. My initial answer should be enough.

Usually, when people ask, “Where are you really from?” what they want to know is that my parents immigrated here from Taiwan.

The other question I’m often asked is “What are you?” or more specifically, “What kind of Asian are you?”

Both of these are pretty rude ways to ask me about my ethnicity.

The solution to this offense isn’t to ask more directly about my immigration status, citizenship status, national origin, or ethnicity. It’s to further explore why someone needs to ask at all.

Sometimes, even when I answer, responses continue to reduce my identity down to inaccurate stereotypes around food and culture.

For example, when I say, “Okay, I’m Taiwanese,” responses have included, “Oh cool! I love pad thai.” Gee, thanks, I’m glad I can remind you of a meal you like – and also, Thailand and Taiwan are different places.

But honestly, do you really need to know where I’m from or what my ethnicity is to interact with me? What are you actually trying to learn about me?

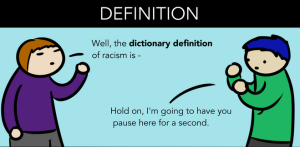

While these questions might seem like a small, innocuous thing, they are rooted in violent and hurtful histories of racism. Even if you might not mean any ill-intentions, here are three reasons that these questions are racist:

1. They Invalidate the Everyday Lived Experiences of Asian Americans

Despite the “multicultural melting pot” image of the United States, the culture of middle class whiteness is still dominant and perceived as “normal.”

Middle class white culture is what’s on television. It’s what’s reflected in the expected routine of everyday life. And any experience outside of this falls into the category of “other.”

Fresh Off the Boat is one of the only television shows (both network and cable) that showcases an Asian American family, and many of the episodes and jokes explore the reality of being othered.

Yet even the name of the show is a joke about recently arriving in the US – demonstrating how the “new arrival” stereotype follows Asian Americans regardless of immigration history.

The nuances and vastness of Asian American experiences just aren’t represented in mainstream culture.

My family has navigated ways to make the United States our current home. My mom travels back and forth between the US and Taiwan every year for work, literally moving back and forth between the two places and two cultures.

For myself, growing up in the Chicago suburbs, I was one of the few Asian Americans at my elementary and middle school. I so clearly remember my mom packing me rice and meat lunches and other kids saying, “Ew, what is that?”

After a while, I only wanted a peanut butter and jelly sandwich for lunch so I could stand out less and not get teased as much. My mom would try, making me toasted chunky peanut butter sandwiches with marmalade.

I grew up feeling there was something about me that just didn’t completely fit with everyone else.

None of my teachers looked like my parents or me – heck, I didn’t meet a Taiwanese American person at the front of a classroom until my last semester of graduate school). While there was a strong Taiwanese community in the greater Chicago area, this community experience was siloed away from everyday school or extracurricular experiences.

Even in college, my “Taiwanese” self was compartmentalized away from my “American” self.

I went to a predominantly white university in the Midwest, and I was people’s first “Asian friend.” The everyday foods I like, such as noodle soups, were seen as adventurous and exciting.

Many of my White friends declined invites to public events hosted by the multicultural student councils because they felt like they’d be out of place. Their fear of being perceived as the outsider paired with the ways they continued to place my foods and my culture outside of their norm, made me feel further out of place.

Yet, it would be “normal” for me to be at events where I was the only person of color. In many friendships up until I graduated from college, I negotiated with hiding or showing parts of myself in order to feel like I fit in.

I am expected to assimilate towards whiteness in order to fit in and be seen as more “American.”

2. They Invalidate the Many Different Histories that Make Up Asian American Identity

The question “Where are you really from?” also implies that Asian Americans can only be from one particular place, despite varying degrees of connection someone might feel towards that place.

“What kind of Asian are you?” homogenizes Asian Americans into one category, erasing the multiple cultures, ethnicities, geographies, and nationalities that make up Asian American identity.

For example, did you know that there are 56 ethnic groups in China?

The question also forces someone to choose one identity.

The question invalidates the experiences of Asian Americans whose families have lived here for generations. It invalidates the experiences of Asian Americans whose homes have been destroyed by war. It invalidates the experiences of Asian Americans who have migrated across many places or came from spaces that they approach as borderless. It invalidates Asian Americans with mixed race and mixed ethnic backgrounds whose families are from multiple places.

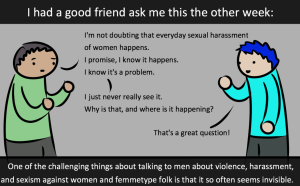

Racial microaggressions are everyday, often unrecognizable, unconscious, or unintentional slights or insults that communicate something hurtful towards a person of color. While the interaction is often a small thing, the impact can be huge.

“Where are you really from?” or “What are you?” are examples of microaggressions towards Asian Americans because they imply that Asians still don’t belong. They exclude and invalidate our American lives and experiences. We’re forever outside of the norm, perpetually perceived as foreign no matter where we call home.

3. They Racialize Asians as Perpetual Foreigners Who Don’t Really Belong

The reality, in a US context, is that except for Native Americans, nobody is really from the United States. For some us, our families immigrated here by choice at some point in history.

Some folks migrated here to seek refuge because their homes are no longer safe. Other folks came here because they were forced to by slavery. Across different diasporas, the reasons for ending up in the US can be painful and traumatic, liberating, both, or many others in between.

However, some people, specifically non-White folks, are racialized in a way as “perpetual foreigners” no matter how long they’ve called the US home.

Despite the Americas being a geographically and nationally diverse region, being “American” has become code for being White and being a US citizen.

US citizens who are White are not thought of as “European Americans” or “White Americans.” Yes, there are lots of folks who might celebrate their ethnicity, such as being Irish American or Polish American, but as these ethnic groups have moved into Whiteness, they also have the choice of being just “American.”

As an Asian American, I don’t have that choice. Because I identify as Asian and am also perceived as Asian, specifically as Taiwanese, I must always qualify my “American” identity as Asian American.

My ethnicity is imposed upon me.

Because of my appearance as “non-White” – specifically as “definitely Asian, but we should find out what kind of Asian” – there’s a divide between how other people perceive me and my actual lived experience.

It’s problematic when folks impose their own realities onto other people’s identities, experiences, and histories.

Behind the questions “Where are you really from?” and “What are you?” there’s a construction that Asian identities are tied to distant, faraway places – and also a demand that Asians justify their belonging to one particular place.

4. It Alludes to Fear and Distance Towards Asians

Historically and currently, Asians are told, “Why don’t you just go back home?” which is another reason why the “Where are you really from?” question can be triggering.

There are many stereotypes and generalizations about Asian Americans that paint us as forever “alien,” which is also the US government’s official term for non-citizens in the United States.

Our food is weird, and we are rumored to eat dogs. We all look “the same.” Some of our names are too hard to pronounce. We’re all Communists (and Communism is dangerous). We’re here to steal jobs.

Do you know who Vincent Chin is? He was a Chinese American man who was murdered in Michigan in 1982. At the time, a lot of folks in Detroit working in the auto industry lost their jobs as the Japanese auto industry rose, and the murderers killed Vincent out of anger.

This xenophobia, or fear of perceived foreigners, that leads to anti-Asian sentiments and racial hatred isn’t new.

Yellow Peril specifically generated terror and fear towards East Asians and led to policies like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that specifically aimed to keep Chinese immigrants out of the United States. During World War II, over 110,000 Japanese Americans were removed from their homes and interned in detention camps.

The South Asian, Sikh, Muslim, and Arab American community has been targeted by hate crimes, harassment, and profiling, especially after 9/11. A couple years ago, the remake of the movie Red Dawn came out, depicting an invasion of the United States by North Korea sparked a lot of hateful tweets about “kicking Asian ass.”

More recently, Jeb Bush has made comments about Asians “taking advantage” of birthright citizenship in relation to discussions around immigration policy.

The question “What are you?” brings up dehumanizing memories of trauma around the perpetual foreigner trope that has led to xenophobic ideologies and action.

***

With these questions, some folks might be really upset. Some might not be that bothered at all. Others might be bothered depending on context.

But the thing to remember is that despite your well-intentioned curiosities, these questions are loaded with histories of fear and exclusion.

Questions that demand Asians share their national origin, nationality, ethnicity, immigration status, or citizenship status continue to cause a lot of internalized pain, especially when they’re asked of someone over and over again.

These questions are reminders that my identities and my experiences are mismatched with what’s expected and “normal.”

To me, the questions also hint that someone can’t find a true point of connection with me unless they isolate what’s different about me.

When getting to know someone for the first time, there are so many things to be curious about. Yet, if you find yourself probing to know where someone’s “really” from or “what” they are, think about why you need to know that about them. Those questions ostracize someone, making them feel like they don’t belong.

There are more inclusive and less invalidating ways to get to know someone.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32