Source: Unsplash

I used to think that all progressive, activist communities provide relief from the rest of society’s judgmental nature.

As a Black woman, I deal with racist and sexist microaggressions all the time. As a queer bisexual woman, I get hate from both straight and gay people. As someone who’s been through sexual and intimate partner violence, I never know when someone will say something insensitive about survivors.

Through feminism and other social justice movements, I found language for these experiences that connected me with like-minded people – people who know what’s up with oppression and who are taking action to do something about it.

As activists, we know exactly how harmful shame and judgment are. It can be so refreshing to work and hang out with people who are considerate and accepting, instead of mistreating each other by following society’s oppressive norms.

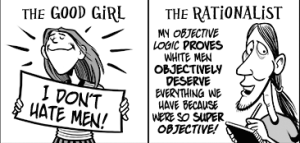

But now I’ve spent enough time in activist communities to know that they’re not necessarily a judgment-free zone. We may be doing our best to avoid oppressive behavior, but in some ways, we’ve developed our own internal standards for judging each other.

I’m talking about how we treat each other when we make mistakes. We do all make mistakes – nobody’s perfect, and developing political consciousness and knowledge is a lifelong learning process.

That’s why accountability is so important in our movements. Owning up to what we’ve done wrong helps us grow as activists and human beings.

But that also means that when we call someone else out for making mistakes, we have to leave room for them to learn.

In some activist circles, we’ve made lots of room for calling each other out, but not as much room to actually make and learn from our missteps.

If your path to activism was anything like mine, then I get why you would follow this tendency. You’re tired of the major challenges oppression has thrown your way, and of the subtle, everyday ways that oppression is perpetuated.

You spend time with other activists partly because you can trust that they understand what you’ve been through – so it’s a big deal when someone breaks that trust.

I don’t know about you, but when I’m in a space I thought was safe, and then a fellow activist is the one who insults me with a microaggression, that feels personal. I expect people in the movement to treat me better.

After all, when it comes to activism, we’re not talking about mistakes that can be fixed by saying, “Oops! My bad.” Oppressive behavior has a heavy impact – and it can be even heavier in the movement.

And that’s all the more reason that we need space to learn. If we exclude everyone who makes a mistake from the movement, then nobody will be left to engage with the vital work of actually interrupting oppressive patterns.

I personally know several people who hesitate to speak out about important issues for fear of saying something “wrong.” Activists hold each other to a higher standard because we consider our circles safe havens.

But the truth is, we all contribute to systems of oppression – even those of us who have committed to doing better. Surrounding ourselves with other activists doesn’t guarantee that we’ll escape problematic moments.

Let me be clear about what I’m talking about here. You get to put yourself first when you’re surviving oppression.

So I support you standing up for yourself and your community, and refusing to silence your feelings when you do it. I’m with you if you have to tell somebody off, straight up, for your own protection.

I support directing our rage at systems of oppression and at the institutions that keep those systems running. I’m all for public protests and acts of civil disobedience that target people and corporations in positions of power to demand that they do better.

These tips are not about tone policing marginalized people to insist that we be nice about our oppression.

But as for how we treat each other, within activist communities committed to doing better, we need more options. Otherwise, calling for accountability turns into shame, punishment, and judgment – instead of cultivating the supportive culture we’re trying to create.

So here are a few supportive options to make more room for mistakes in your activist communities – and still hold people accountable.

1. Define Your Values as a Group – And Keep Your Vision in Mind When Someone Makes a Mistake

One way to prepare for hard moments is to be clear about what you’re working to build together – and what principles and values will help you build it.

With groups of several different people, it’s only natural that not everyone will be on the same page at all times – especially when intense feelings and strong opinions are in the room.

As for groups of activists working around issues of injustice? We have all of the above. That’s not a bad thing – passion is part of what makes us so powerful.

But it also means that we can lose sight of our goals when someone leads us off course by doing something oppressive.

If your group has a structured base, like a women’s organization, you can define your group values as part of your work. For instance, have a leadership team brainstorm a list, then share it at a community meeting and ask for feedback and more ideas.

For an activist community composed more of informal connections, like friends who aren’t all affiliated with one organization, it’s a little more difficult to establish shared values – but it’s not impossible.

We actually do it all the time, such as when we talk about our common interests or post on social media about the issues that matter to us. We’re essentially saying, “This is important to me, and I appreciate having you in my life if you understand why.”

You could even introduce a more structured way to put your values out on the table – like creating a social media group of like-minded people for discussions on intersectional feminism. Then you can brainstorm your values together.

Explicitly stating what you value can help you identify when an accountability process is necessary.

For instance, your women’s organization can specify that behind your support of women is the goal of fighting systematic sexism.

You can agree to do your best to live up to these values, but people will make mistakes. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll be immediately ejected from the community.

Identifying the problem is the first step to accountability. If someone perpetuates sexist ideas, you can bring up your established group values to point out that they’re out of line.

I know it would feel incredibly frustrating to encounter sexist ideas after you’ve all agreed to fight sexism. You might wonder why you should even bother giving a second chance to someone who’s deliberately violating this space.

There are many possibilities here. Maybe the person doesn’t even realize how their words relate to sexism, and a chance to learn would shift their perspective.

You’re aiming for this person to take responsibility and commit to changing their behavior. As activists, this relates to our ultimate goal of changing oppressive behavior and systems in our culture.

By keeping your vision and values in mind, you can name what needs to come out of an accountability process, and help the person responsible for harm remember that this isn’t a personal “attack” – it’s about what you’re all trying to build together.

2. Talk About What Respect and Accountability Mean Outside of Harmful Incidents

You’ve already got a good start for this step – a conversation about group values gives your community space to create a shared vision of respect and accountability.

Tensions can run high when somebody does something harmful. The person responsible might be defensive. People who are hurt can be angry or sad, and they should be able to express how they’re hurting.

To create a supportive space for hard feelings, it helps to work out the details of how everyone wants and deserves to be treated – and not just when someone’s messing up.

If I’m in your community and we have regular conversations like this, then I know that I’ll have the chance to change my behavior in the inevitable case that I make a mistake.

I also know I’m not alone if someone in the group hurts me. We’re going to address it as a community, instead of sweeping it under the rug.

During these conversations, you can find answers to key questions about the best accountability process for your group.

For instance, how will you deal with any existing hierarchies in the room, like if a group leader is the one who causes harm? How will you navigate privilege, like making sure trans people aren’t silenced by cisgender people acting on cis privilege?

How will you center the person or people who are harmed when something oppressive happens?

The more you make space for this conversation, the more your community can build an accountability process that’s best for all of you. You can revisit it often and be open to change, but at least you have a foundational plan to work from.

3. Stay Grounded in Your Personal Experience and Feelings

You might think you’d have to silence your feelings to make room for other people’s mistakes. But feelings are not the problem – what’s usually missing is the space to hold our emotions.

I say invite your emotions into the room – so we can learn how to navigate hard feelings as a community, and remember that emotion is nothing to be afraid of.

Hard data and big picture concepts are useful for understanding systems of oppression in general terms. But our personal experiences and perspectives help connect those concepts to our real lives.

So if I’m waging a public anti-femmephobia campaign, statistics and analysis about how femmephobia makes feminine people unsafe would come in handy.

But how much can statistics capture the details of my personal experience with femmephobia?

Say it’s not a public campaign. It’s a fellow activist in my community who puts down “girly girls” when she’s describing what it means to be a “strong woman.”

I could tell her I like to wear makeup and dresses, and it hurts to hear her write me off as not being “strong” because of it.

By staying grounded in my experience, I invite her to face the impact of what she said – so she knows it’s not about whether or not she “meant to” hurt me.

I also invite her to connect with me on a personal level. She’s not some faceless entity – she’s a person who’s capable of making mistakes. And I’m not some nameless victim – I’m a person who can be hurt by her mistakes.

Being honest about hard feelings and hurting each other is challenging, and it’s up to you to decide when you’re comfortable being open. When you’re hurt and feeling vulnerable, it makes sense if exposing your emotions feels like too much of a risk.

But when you can speak from a personal place, you deserve to be heard, and to be treated better.

Many people can do better – they just need some perspective on how. If you share how their behavior hurts you, they can grasp in concrete terms what they need to change, and how they cause harm if they don’t.

4. Ask Questions About Where the Person Responsible Is Coming From

Of course, intentions aren’t everything. But if someone makes a mistake and you can find out where they’re coming from, you might be able to get some information about why they think their behavior is okay.

This will help lead them to recognize what they’re missing.

Remember, there’s a reason people are stuck on the oppressive status quo. Even within activist circles, it takes time to unlearn the ways we’ve all been conditioned to perpetuate systems of oppression.

For instance, the system of monosexism reduces sexual orientations to gay and straight – and many people still perpetuate ideas that erase people attracted to multiple genders.

If a gay man in my community jokes about convincing bisexual men to “admit they’re really gay,” I could assume he’s an unapologetically biphobic asshole – in which case, I wouldn’t want to be around him.

But it’s also possible that he hasn’t considered how hurtful his joke is. As a fellow activist, he might apologize if he found out.

Regardless of where he’s coming from, I’d still be pretty pissed about the joke – and I don’t have to hold back from letting him know that when I talk to him about it.

I can ask questions: “What do you mean by that? Do you think men can’t really be attracted to two or more genders?”

An answer like, “Well, I said I was bisexual before I admitted I was gay” lets me know exactly where he’s coming from.

I can say, “Oh, so that was your experience – I’m glad you found what worked for you. But personally, I know many bisexual men, and they get tired of assumptions that they’re secretly gay. Hearing that joke also makes me feel like I can’t be open about my sexuality with you.”

This might be the first time he’s ever had his monosexism challenged. He has an opportunity to change his perspective now that he knows what he’s getting wrong.

5. Find Common Ground

If we’re talking about addressing influential political figures like Donald Trump, sitting down to find ways to relate is not on my priority list. His overtly racist and xenophobic rhetoric is dangerous, and it needs to stop, period.

But I’m not going to approach people in my activist circles like I’d approach Donald Trump.

Once we’ve committed to building a better world together, there’s probably some common ground that we could work with.

For example, some activists are pretty clueless about what whitesplaining looks like – they’d speak over me without even realizing they’re whitesplaining.

People who whitesplain are often implicltly acting on the idea that people of color are uninformed, even about our own experiences with racism. It’s really shitty to have a fellow activist treat me like I’m incompetent, and I’m totally justified in getting angry about it.

Finding some common ground can give me hope that these activists don’t have to stay clueless about what they’re doing to me.

I can relate to the ways they’re marginalized. To a woman who’s whitesplaining, I can say, “You know how men interrupt you, and mansplaining’s really annoying? Whitesplaining is similar, and you’re doing it to me.”

If she gets how privileged ‘splaining feels, she can understand why I’m hurt.

We’ve all been on both sides of injustice. Finding common ground is another way to help people recognize the connection between their own behavior and the systems of oppression they want to take down.

6. Recognize People’s Humanity – And That Everyone Shows Up Differently

When we view groups as single entities – like communities, organizations, and publications – it’s easy to overlook the human beings within them.

We become invisible to each other, and forget to treat one another like fallible human beings with the capacity to grow.

Think of an organization putting on an event focused on social justice. You’d expect their promotional materials to contain inclusive language.

If they use language that excludes a marginalized sexual orientation, disability, gender, or other identity, it’s possible to rally up a campaign to declare that this organization doesn’t care about the group they’ve excluded.

But it’s also possible that their exclusive language is a typo. Or it was overlooked due to a learning disability. Or the person who wrote the statement didn’t know that their language was leaving somebody out.

At the heart of our movements are human beings – not robots incapable of making mistakes.

Recognizing each other’s humanity doesn’t mean we excuse harmful behavior. It means we recognize that mistakes are opportunities for growth – they are how we learn as humans.

Social justice jargon is challenging because not everyone has the chance to study the “right” vocabulary in school or online. We’re all learning more every day about how to be inclusive.

The person who created the materials for this event needs to know that without inclusive language, people get hurt. Of course it makes sense to tell them they have more language to learn.

But there might be other options besides making them leave the community until they memorize the entire social justice dictionary. What if their graphic design skills for the flyers are on point?

We all show up differently, with a different set of skills. This is a chance to connect the graphic designer with someone who knows more inclusive language for a collaboration on flyers that look good and welcome everyone.

No single person has all the answers – but if we recognize the humanity in each other, we can build our collective capacity to figure things out.

***

We miss out on a lot of wisdom in our communities if we write people off as disposable for making mistakes.

If I decide I can’t learn from someone who’s imperfect, then I would pretty much never learn anything from anyone.

Everyone has something to contribute to the movement, and we’ll only get stronger if we learn from our mistakes.

Of course, even with all of these tips, an accountability process may not go super smoothly. They all rely on the hope that the person who has messed up is willing to own up to it and do better.

That’s not always the case, and for the sake of yourself and others, there might be instances when you need to remove someone from the community if they’re unwilling to make a change.

But at least you’ve offered space and opportunity to grow – which can add to the whole community’s growth. You still get to put yourself first when you’re hurt, and you also get to keep moving toward our greater collective vision.

We can work toward that vision of a culture without oppressive shame, and we don’t need to judge each other to get there.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Maisha Z. Johnson is the Digital Content Associate and Staff Writer of Everyday Feminism. You can find her writing at the intersections and shamelessly indulging in her obsession with pop culture around the web. Maisha’s past work includes Community United Against Violence (CUAV), the nation’s oldest LGBTQ anti-violence organization, and Fired Up!, a program of California Coalition for Women Prisoners. Through her own project, Inkblot Arts, Maisha taps into the creative arts and digital media to amplify the voices of those often silenced. Like her on Facebook or follow her on Twitter @mzjwords.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more