A runner, photographed from behind, jogging on a forest trail.

One of the most common questions that I get about thin privilege, by far, is whether or not thinness really counts as a “privilege.”

After all, if anyone could potentially achieve thinness, then is it really an issue of social power? And if folks have put a lot of effort into attaining and maintaining that body, don’t they deserve the associated rewards?

And I get where this question comes from. Because oftentimes, when we talk about privilege, we note that it’s something undeserving that’s granted to you based on birth or circumstances.

And a lot of that time, that’s true. I can’t change the fact that I’m white or that my parents grew up working class, for instance. That’s just a part of my social location by default – that’s the situation that I was born into.

But when we name power and oppression, as doled out by systems, as things that are largely out of our control, it can be confusing to think through how something we believe we can “work for” fits into that narrative.

The answer to how this is associated with privilege, though, is in the question itself. It’s just hiding from you.

Because within the very question of whether or not attained and maintained thinness really “counts” as privilege are assertions that 1) we’re all starting from the same place, 2) our bodies are malleable, and 3) some bodies are more inherently deserving of respect than others.

And I call BS on all of that.

So here’s why.

1. The Bootstraps Myth Is Bullshit

Most often, this argument of being able to “work for” success is applied to class: that if you just work hard enough, you can pull yourself up out of poverty. On a social level, we’ve bought into the myth that if you’re poor, it’s your own fault for “not working hard enough.”

On the flipside, we believe that if you’re rich (or go to a “good” school or have a “good” job), you deserve it because you poured a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into it.

Now, this isn’t to say that you didn’t pour blood, sweat, and tears into your achievements – just that those aren’t the only (albeit gross) ingredients to your success. This idea – that all we have to do is work hard to achieve what society deems as “greatness” – is a product of a capitalist system that values productivity above all else.

And that’s why we call this idea “the bootstraps myth.” You can read more about it here, but the basic idea is this:

If you’re productive, you win. The harder you work, the more you earn, whether that’s financial or social power or something else. And anything you’ve earned is well deserved.

But in reality, the bootstraps myth is used to shame poor and working class people who, for various complicated reasons, actually cannot achieve the kind of mobility that the myth promises. The myth, in reality, is just a dangling carrot. It entices you to put all of your effort into moving forward when, in truth, you’re staying still.

But because we have a few rags-to-riches stories, we continue to tell poor and working class people, “If so-and-so did it, so can you!” We say, “If you want to have money so badly, you just need to work harder! I worked my ass off, and that’s why I have these privileges – because I earned them.”

But this narrative actually ignores the fact that there are multiple obstacles holding poor and working class people down, away from this picture of success. And this narrative also ignores the fact that people with this success didn’t face those same obstacles.

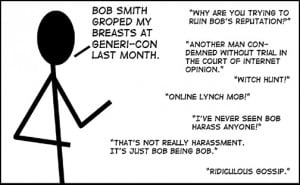

Did they have a hard time? Yeah! Working hard is no piece of cake. But there’s a difference between “I worked hard” and “I’m facing near-impossible obstacles.” This comic does a good job of illustrating that.

But in a capitalist system, we love these stories. We love believing that everyone has the same opportunities as everyone else, so long as they put the effort in to get what they “deserve.” These stories grab our attentions and pull at our heartstrings again and again and again. It’s literally the American dream!

And this exact same logic – yes, indeed, the bootstraps myth – is applied to conversations about thin privilege and fat oppression.

We say, “If you don’t want to be oppressed, why don’t you just lose weight? If life is so hard being fat, have you tried not being fat?” We say, “Society is only treating you horribly to motivate you to change your ways and become a more productive member of society!”

We say, “I earned my thin privilege through hard work and dedication. And so I deserve the benefits of my effort.” We say, “I’ve wielded control over my body, and that’s won me these privileges.” We say, “I deserve something for all of the sacrifice that it’s taken me to create this body.”

And just like we love rags-to-riches stories, we loooove fat-to-thin stories. Why do you think The Biggest Loser is still on air, despite its being terrible? We’re desperately drawn to the idea that an underdog can win with a little effort.

But the problem here is the same as when the bootstraps myth is applied to class: We’re simply not taking the realities of the obstacles into account.

2. Our Bodies Actually Aren’t Projects

I know that this one is going to be hard to swallow, but I want you to stick with me for a second: Just like you’re born into situations that might allow you to make more money with less effort, you’re also born into a body with genetic predisposition.

There is some amount of “work” that we can put into our bodies. Our diets and fitness regimens play some role in our bodily aesthetics; they’re not entirely disconnected. But the common refrain about calories in and calories out simply isn’t the only equation at play when it comes to how our bodies look.

If I eat intuitively and move joyfully, I will remain around the same size and weight. It will naturally fluctuate, of course: I’m going to eat and rest more in the cold weather months, for example, and therefore gain weight to protect me against the northeastern freeze.

And there are things that I can do to change that – to lose or gain fat, to lose or gain muscle – but aside from unhealthy measures, there really isn’t much I can change significantly.

We want to believe that our bodies are incredibly malleable. We’ve been taught by society that we can constantly be “improving” our bodies, and that if we’re not, we must be lacking willpower. And we’re supposed to be embarrassed by that – of this supposed physical proof that we’re lazy.

But in reality, our bodies aren’t very malleable. In fact, they probably shouldn’t be. They’ve got millions of years of instinct wired through them. And me? Little old me? I’ve only been alive for 31 years. Honestly, what the fuck do I know?

We want to believe that we can control our bodies. But really, our bodies control us. They’re little ecosystems. They’re smarter than us. They want to do all they can to survive, “will power” be damned.

Even just psychologically speaking, this is obvious: Our instincts are controlled by our mid-brains; our decisions controlled by our frontal lobe. And guess which is going to override which every. single. time.

Scientifically speaking, long-term bodily changes are almost impossible for most people to maintain without resorting to unhealthy measures – and for some folks (like those living with PCOS, for example), it’s literally impossible. Because the lengths that we go to in order to attain certain bodily ideals go against our bodies’ intuitions. They literally go against our survival instincts.

If you want to read more about that, Linda Bacon and I wrote this article. But I also think that a combination of Bacon’s Health at Every Size, Harriet Brown’s Body of Truth, and Joan Jacobs Brumberg’s The Body Project is the safe bet to having a relatively well-rounded base understanding of this.

But the overall point is this: You don’t actually “work for” your body. It just kind of is.

So just like no matter how much work you put into your financial standing, if you start life out poor, you’ll likely stay poor, the same goes for your bodily aesthetics: If your body starts out fat, you’ll likely stay fat.

And if you’re born into a situation of privilege – like coming from a wealthy family, for instance, of being genetically predisposed to have a thin body – then you’re likely going to maintain that, too.

3. No Body Is More Deserving of Respect Than Another

Despite this, we still tend to associate body types with levels of (un)productivity. Now, the problem with that, especially in a capitalist system that equates your level of worth with your level of productivity, is that we then start to place values on bodies.

And in a conversation with the brilliant Stacy Bias recently, this is what she taught me: In a system that values productivity, we value bodies that symbolize productivity to us; simultaneously, we devalue bodies that symbolize unproductivity.

As is, we currently associate fat bodies with greed, sloth, and gluttony, which equates to sin. Culturally, we hate fat bodies so much (which hasn’t always been the case, by the way) because we register them as having failed at productivity.

We believe that fat bodies are the result of excess, laziness, and insatiability. And we don’t think that any of these traits are controlled enough – and if only we would control our input, we think, we could capitalize on our output.

Meanwhile, while we’re regulating how fat bodies can be more productive, we’re associating thin bodies with hard work and control – the very shit that capitalism loves!

We buy into (and then push) the myth that it takes work to have a thin body! We talk about thinness in terms of the rigidity of dieting and the dedication of going to the gym. We think of thin bodies in terms of what they’ve had to sacrifice to get to where they are.

And I’m using the word sacrifice very purposefully here. Because I know you know what “sacrifice” means in a culture whose values are founded in Puritanical beliefs: salvation.

We believe, implicitly, that because the people who own thin bodies have sacrificed, that they therefore deserve salvation. Meanwhile, because fat bodies have sinned, they deserve damnation. And so we do damn them. All the way to hell.

The problem is that in reality, a little bit of “sacrificing” or a little bit of “sinning” isn’t really going to make a huge difference – not in our afterlife, and sure as shit not in our bodies.

Further, the direct association that we make between “working hard” and “having a thin body” is problematic, as noted in section #2: A fat person can work just as hard at dieting and exercise, but still not “achieve” the outward markers of that work.

So the entire notion that thin bodies are “worked for” and therefore have “sacrificed” and therefore deserve “salvation” is faulty as all hell.

But it’s also important to note that for the very, very few people for whom the bootstraps myth actually works – for the very, very few people who pull themselves out of poverty, or for the very, very few people who maintain significant weight loss – they still have privilege.

Because privilege isn’t actually dependent on whether you “worked for” it or not.

For example, I’m wildly privileged on the basis of being a future PhD-holder (if I ever finish this damn dissertation). I have a ton of (traditional) educational privilege. And if anyone tried to tell me that I didn’t work hard for that, I would probably scream.

But just because I worked hard for it doesn’t mean that I’m not privileged by it. And it also doesn’t mean that I actually deserve that social capital.

Similarly, you don’t deserve more power based on the kind of body that you have.

You just don’t.

***

The thing about privilege – whether it’s circumstantial or gained – is that it’s unfair. It’s inequitable. It’s an injustice. Because regardless of how you come by your privilege, it can only exist based on the oppression of others.

Privilege isn’t about what you work for and what you don’t – it’s about holding social power over those who are oppressed. And the only way that thin privilege can exist is if the oppression of fat people exists.

And therefore, if you believe that you “deserve” your privilege (perhaps because you “worked for” it), then you also inherently believe that others “deserve” to be oppressed.

And I don’t think you really feel that way, y’all. At least, I hope you don’t.

But when we talk about “working for” and “deserving” privilege, we have to realize what that entails – and stop thinking in those terms altogether.

Special thanks to Ivy La Felicia for helping make this article what it is.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Melissa A. Fabello, Co-Managing Editor of Everyday Feminism, is a body acceptance activist and sexuality scholar living in Philadelphia. She enjoys rainy days, tattoos, yin yoga, and Jurassic Park. She holds a B.S. in English Education from Boston University and an M.Ed. in Human Sexuality from Widener University. She is currently working on her PhD. She can be reached on Twitter @fyeahmfabello.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more