A person stares out a window, appearing sad, with their fingers laced together and held up to their face.

Growing up, I refused to wear pink to school. No purple, either.

My mom tried and tried, but I refused. At home, I wore tutus. I had a whole chest of sequined dress-up gowns. I’d cover myself in body glitter, lacquer fruity dollar-store lip gloss onto my lips, and make a mess of rouge on my cheeks and eyelids.

At home, in private, I felt safe being a “girly girl.” At school, I condemned it. I was an “I’m not like other girls” girl, in public. I was one of the chill ones.

I can’t remember whether I learned to disown my femininity or my Blackness first. But I hid that, too.

I didn’t invite my white friends to come to my house in my all Black neighborhood. To prove I was “smarter,” I made hyperbolic displays of how awkward African American Vernacular English sounded on my tongue. I only ever talked publicly about the pop-punk I loved, not the hip-hop I blared in my bedroom.

I was ashamed of the parts of me that fit stereotypes, and I shamed people who didn’t seem to be shaming themselves.

I knew what it meant to be a Black girl in my environment, and I wanted more. I knew it meant being shoved into a box of low worth. I wanted to be valued. And I thought that breaking the box, asserting that no part of me fit into it, that I could not be contained by it, would grant me value. I tried to prove that I wasn’t any of the things they thought I was, that I was better than that.

Members of marginalized communities do this often.

We want to be more than what we’re told we can be. We want to be treated better than people like us are treated. And so we try not to be like us. We try to be better than us. Searching for self-worth, we reinforce hierarchies amongst ourselves correlating to our proximity to the people in power.

But that’s not where true worth is.

Worth is in reclaiming the parts of us we’re told to be ashamed of. Worth is in smashing the standards, in challenging the way we’re treated, in demanding to be valued as we are.

In our efforts to escape the system, we unintentionally participate in the system. Subjugating others for self-worth does us, and our peers, a disservice.

Here are four reasons why – and how we can do better.

1. Because So Many of Us Struggle Regularly to Value Ourselves

It’s easy to intellectualize our worth. It’s not so easy to feel worthy when it counts.

Marginalized people are flooded with reminders of how little we matter to the masses, regularly. And for a lot of us, it means we’re constantly battling that narrative both externally and internally.

It’s hard as hell to navigate the world in a marginalized body. It’s hard to value yourself instead of resenting who you are. Subjugating other marginalized people is merely a manifestation of that – but a damaging one.

It may ease my pain for a moment to pretend that I’m inherently more valuable than a darker skinned Black woman, or to pretend being married makes me more worthy of respect than a single mother, but neither are true.

Not only do I assign myself a false sense of worth based on malleable standards, but I take the side of the oppressor in that other woman’s personal battle. I affirm her unworthiness, and become an obstacle on her path to liberation.

Growing up marginalized is traumatic. We’re robbed of dignity and disrespected. We’re undermined and told repeatedly that we aren’t enough. And it’s super difficult to unlearn that kind of training.

That unlearning process is disrupted when our value is undermined, especially by someone who knows our struggle.

Instead, we need to hold space for one another to get through the struggle. We need to stand in solidarity, to affirm the validity of that struggle.

If we want to get serious about demanding value for ourselves as marginalized people, we need to stop robbing those with different lifestyles or experiences than us of value.

2. Because We Mimic Our Oppressors

It’s natural not to want to be reduced to who the system says we are. We’re dynamic, and the system says we can’t be complex. But it’s unhealthy to direct our anger at the system at each other instead.

If the system says that being uneducated makes you less valuable, and that Black people are largely uneducated, the answer is not for educated Black people to shame uneducated Black people. Education has absolutely nothing to do with how we deserve to be regarded.

The system is wrong for claiming that one of us is more worthy than the other. But instead of upholding that truth, we get caught in a web of affirming the system while trying to prove it wrong about us.

This is no accident. This is a trap intentionally laid for us. We’re pitted against each other on purpose. The system flourishes when we’re too distracted – chasing the crumbs of worth we get from putting each other down – to call it out for screwing us all over.

And when we’re starved for worth, it makes perfect sense to chase crumbs. But we’ll stay undernourished as long as we support the system in this way. It wins when we do its work for it, when we lash out at each other instead of joining forces.

The system loses when we affirm one another’s experiences and lifestyles as valid, despite the differences. It loses when we decide we’re all worthy of respect and compassion and value – and start asserting it.

The only thing shameful is a system that tries to convince us to be ashamed of our existences. It depends on our shame to survive.

3. Because Our Self-Worth Becomes Dependent on Others Having None

When we use someone else as a boost to move up a level on the societal pyramid, our elevation is dependent on them staying beneath us.

Their moving up a level means that our foundation rattles. It means that we run the risk of falling. Their success becomes a threat to us. We become desperate to secure our positions, so we demand that they stay in theirs. And sometimes, we get downright vicious in order to protect our place.

There’s an inextricable linking of our worth to the denial of theirs, leaving our sense of self-worth volatile and wavering.

This is largely borne of the scarcity mentality – a byproduct of our current system that says that there’s only enough to sustain some of us, that there has to be haves and have-nots.

This is a fallacy. The major issue is distribution, but it has a serious effect on marginalized people specifically. It grants an obtuse portion of resources to people who uphold white, wealthy, ableist, cishetero patriarchy – and leaves the rest of us to fend for the crumbs.

We’re left to believe there can’t be many marginalized people succeeding in the same space. We’re then in constant competition for reinforcement only granted to very few of us.

But if we can break down the notion of a pyramid at all (where those on top deserve the most and those on the bottom deserve the least), if we can break down the idea that some people are inherently more valuable than others, then we can begin to dissipate the contention and disparity between us.

We can create a system where there’s room for all of us, however we are – where we all have something worthy and important to bring to the table, and have the space to bring it.

4. Because Our Value Is Determined by Our Humanity, Not Our Circumstance

Not a single one of us is more or less deserving of dignity than another.

We all deserve to have our humanity respected. Our systems, however, disagree. Various oppressions, working together, have created a set of absurd standards that determine who is worthy of their humanity, and under what circumstances.

It does this to excuse the ways in which it exploits and abuses the marginalized.

These standards are often called respectability politics – and a large portion of subjugating one another is executed through this form.

Marginalized people partake in it because we reasonably want to have our humanity protected. It’s a coping mechanism that makes us feel like we have some power over how other people treat us. But we don’t.

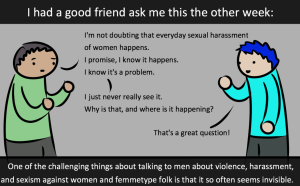

Instead of making a better circumstance for ourselves, we make sure that all kinds of atrocities against others are excused. A woman in a short skirt is assaulted, and we say it was the skirt. A Black girl, righteously indignant, is abused by a school resource officer, and we blame the indignation.

We do it so we won’t be treated like they’re treated. But as largely unprotected as marginalized people are, we’re never safe from that kind of mistreatment until we start protecting one another.

***

How we speak, or how much education we’ve had, has nothing to do with how much we have to offer intellectually. How we dress has nothing to do with our right to bodily autonomy. Our human value does not increase with our fiscal value.

We have to destroy the ideals that say it’s possible to be reasonably stripped of our human rights. No circumstance exists in which we stop deserving to be valued.

The more we search for validation from the system, the more we’ll find ourselves deprived of it.

It depends on our devaluing to function; we won’t find a reliable source of it there.

We don’t need its bogus standards to find ourselves worthy of the care and respect we deserve. We deserve something stronger than the wavering worth that the system has to offer us.

And we can find that truth in ourselves and in each other, through fierce affirmation and advocating, instead of putting one another down.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Dominique Matti is a writer, editor, ruminator, and cool mom based in Philadelphia. Her work centralizes Black womanhood, and healing from both individual and societal trauma. She spends her free time napping in unconventional places, guzzling coffee, trying to master magic powers, and feeling all the feelings. She spends her paid time managing, writing, and editing for the Philadelphia Printworks blog. You can check out more of her writing at medium.com/@DominiqueMatti

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32