(Content Warning: mention of death; eating disorders; misogynist, racist, anti-queer, and anti-trans violence)

I learned to be a girlfriend through ’90s American rom-coms.

90% of the time, I learned, I had to be laughing or cutely disagreeing with my white leading man.

At some point, I had to pose a challenge to him, more along the lines of “Pick me, love me, let me make you happy” and less along the lines of “Please realize that patriarchy is hurting us and work with me to dismantle it.”

My partner learned to be a boyfriend by dating girls who could play these American characters better than I could.

I’m not straight nor white. My most honest gender is non-binary. I grew up in what we call a developing nation. I spent a decade of my life starving myself and imagining myself dead.

I’m also straight-passing, cis-privileged, and light-skinned. In many ways, my partner and I proceeded with our relationship as if I were a straight, white, “all-American” gal.

His family and friends know I’m important to him. They cook me vegan food, lend me winter coats, and call me “vibrant” and “pretty.” I tell myself to be grateful – and I am.

But once, his friend’s wife, a white woman, told me, “People get so offended since the Civil Rights Movement.” Once, over the course of a game night, his friend called me a bitch and a slut, and then asked if my partner and I have anal sex. And once, his friends were cackling over an iPhone screen, and when the phone reached me, all I saw was the Tinder photo of a genderqueer person.

In all these situations, instead of making a decision I could respect, I chose to be, first and foremost, a girlfriend – a quiet, indistinct, likable girlfriend.

I said nothing because an evening with friends had to go smoothly. I stopped asserting my needs as a queer person, a person of color, a person of the female experience, a survivor of trauma.

The more time I spent with my partner’s community, the more agitated I became. I would sob afterwards in his car, in his room, drilled down to my core by a feeling I couldn’t define.

That feeling was invisibility. That feeling was namelessness.

To my partner’s face, I called the feeling discomfort. The overwhelming expectation was that I would hold in my discomfort, he would hold my hand, and I would get a kiss and a thank you at the end of the night for convincing everyone that I’d had fun. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Neither my partner nor I questioned this cycle.

Here is context you might need: In the last three decades, not one man has stayed faithful to my mother. Like me, she lives her life as an insecure woman of color. I have learned from her and the men who hurt her that I can’t ask too much of my partners.

I asked my partner once if he has ever been afraid that I’ll leave him in the same way I am always afraid he will leave me. He said no.

He’s a privileged, white man, and he’s been loved well throughout his life. He knows he “deserves” me, and he knows I’ll stay.

If you’re a person with power and self-certainty, it’s important that you notice when your partner withdraws, when they ‘re pretending they have no feelings or needs because they may be de-emphasizing their needs in order to create more room for yours.

Your partner shouldn’t have to disrupt racism and sexism alone, even if you don’t think you’re perpetuating either.

Society perpetuates them, and unless you listen to and back up your partner, your partner will be put through pain that will ultimately consume your relationship.

If you’re unsure about how to initiate a conversation, here are some potential starting places.

1. ‘Sometimes I Make It Hard for You to Show Up Fully – How Are You Doing?’

I’ve made the joke that my partner wasn’t ready for an advanced-level girlfriend like me.

Because it’s not enough that he asks me what I’m feeling. That’s beginner-level shit.

I need him to acknowledge that sometimes, he has shown impatience when my trauma’s have shown up as feelings that weren’t poignant, contained, or novel.

I need him to acknowledge that it’s hard for me – a person who was repeatedly told by my family that I was ugly and crazy – to be transparent with a man whose emotional distance seems to confirm that I am.

Once he started to recognize this and hold it to light in our conversations, we started becoming honest with each other.

2. ‘My Circle Is Predominantly White – How Would You Feel If I Talked to Them About Respecting You as a Person of Color?’

Had he asked me if he could do this three years ago, I might have said no.

I thought: No, your family will think I’m high-maintenance. Your friends will think I’m shit. They’ll all think that I think they’re racist.

If he offered this now, I would say yes.

Had he oriented his family and friends on Allyship 101 three years ago, I wouldn’t have felt compelled to smile as white people told me that I speak “perfect English” or that I come from “hard-working people.”

And there was a double standard: My partner used to prep me.

He used to tell me repeatedly, “It matters to me that you’re there. It matters to me that we share community. Could you try harder to connect with [insert friend or family members’ names here]?”

And so I would go, say please and thank you, help with the dishes, and keep white people feeling comfortable about their race, upbringing, and power.

He could’ve prepped his friends.

He could’ve said: “Hey, I get that we’re straight, cisgender, white men, and this often means we’re encouraged to take up all the air in the room. But maybe you should ask my girlfriend questions about her life and really affirm what she says, so she doesn’t feel the need to censor herself to avoid a situation where you belittle her.”

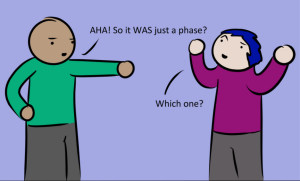

3. ‘My Circle Is Predominantly Straight – How Would You Feel If I Talked to Them About Respecting Your Queerness?’

Once again, three years ago, I might have said, “I’m nervous enough. Don’t you dare fucking out me.”

As it turns out, he has a hometown contingent of friends who are devoutly Christian. I don’t talk to them about gayness. In fact, sometimes, I’ll pause in the middle of stories to stop myself from saying the words queer, butch, femme, dyke.

At dinner or after dinner, I have been afraid of what his people would say or not say to my face if I outed myself.

I wish my partner had had the conversation with his community and known ahead of time if they believe queerness or gender-smashing sends you to hell.

I wish he had known ahead of time if his parents would use someone’s pronoun – not just he and she, but also they, ze, or no pronoun at all – and if they would honor someone’s preference without ever implying it was too difficult or unnecessary.

I wish he had known if his people could listen to me talk about kink, polyamory, sex work, and other realities of my community, without making faces about it afterwards, in private, or to each other.

We didn’t know. So I hid myself.

4. ‘If My Community Fucks Up, How Would You Like Me to Hold Them Accountable?’

Accountability is a non-negotiable.

But depending on the situation, I may want to speak for myself, or I may want you to speak up in the moment, or I may want you to address the fuck-up at another time – that is, when the bride and groom have left the venue.

My partner looks like a young Matthew Fox. He looks so sharp in his leather oxfords and crisp button-downs.

He’s the kind of white man who people view as respectable. If he tells people they fucked up, he’s likely to be believed. If people need to be held accountable, he has their attention and all the credibility.

When I’m vastly outnumbered by straight people, white people, or people who know each other, I want my partner to leverage his privilege on my behalf.

But when I can do so safely, I want to speak for myself.

Otherwise, we risk setting him up as my default savior, and every situation gets “resolved” because people decide to give him respect.

5. ‘What Triggers You? What Keeps You Grounded?’

I come from parents who passed on their traumas, including the not-so-plesant gift of post-traumatic stress.

I know my mind is brilliant. I also know it’s quick to be triggered.

In the face of mainstream expectations (she needs to visit, she needs to chill, she needs to smile), I’m at a disadvantage.

I put in twice the effort to seem half as sane as my partner and twice the effort to stay present when I am listened to half as much.

When my partner takes me into his “territories,” it’s often for days at a time, and my emotional resources are wrung out by the first night.

He does his best to provide me care – I see this and I’m grateful. But I question anyone’s urge to pin a medal of honor on him for doing this.

He isn’t rescuing me. We both put in work.

I repress parts of myself to show up at his people’s celebrations (see above). I do this because it means so much to him that I’m there. But my anxiety and depression deepen as a result.

It’s only fair that he pays attention to this happening and offers me support.

6. ‘Capitalism Is Less Kind to You – How Can I Support Your Sense of Security?’

Up until this past fall, my lack of money made me anxious.

My partner was making eight times as much as me, while my friends were crowdfunding for their healthcare, and my siblings were being evicted from their childhood home.

If my partner and I had been honest with each other then, I would have told him that I found it really triggering to spend time with his people who purchase brand new cars, eastside condos, and three-day passes to live music festivals.

I was at a point in my finances where a pound of grapes was a splurge.

Before our trips to his hometown, I wish I’d asked for a conversation about what was expected of me financially.

Two Christmases ago, I made these sweet little cards for each member of his family. I drew detailed cartoons on the covers and wrote long notes inside.

When I showed them to my partner, I expected praise and kisses. He said, “Could you get my family something else, too? Like a board game?”

It wasn’t really a conversation. It was an expectation.

His family was putting me up for a week, so I owed them a more expensive gift. I was too embarrassed to say that I wasn’t working enough at the time to feel good about spending forty dollars on a board game.

So I spent the money.

If there’s a real privilege differential between you and your partner, there’s probably a real difference in your readiness to state your needs. My partner is comfortable stating his.

I’m learning to be comfortable stating mine.

Don’t expect to get an honest or agreeable answer to every question you ask. Understand that asking “Could you get my family something else? Can you pay for gas this time?” may become a deeper conversation.

Frame every question like you have time to have a longer conversation, like you’re willing to hear more than agreement.

***

My partner has learned to tell when I’m triggered.

Sometimes, he’ll tease me gently by saying “Your eyes just glazed over.” When I’m further gone, he’ll say, my hand in his, “We’re on the same team.” Even if he can’t quite reach me, I hear him.

Here is who we are as a team: He tells his friends that I’ll be joining the trip, but spending most of it alone to write. He credits me proudly and consistently for all my emotional labor.

He advocates for me, at my request, and doesn’t expect to be deified for this. He doesn’t speak for me when I haven’t asked him to, and he asks interrogators to give me space.

My partner is on my side. Which I don’t say as a cop-out, as a way to slap a shiny bow on our very real challenges. I say this because he gets it: This world isn’t set up for me.

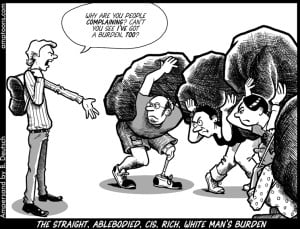

Men who look like him are decision makers. They are storytellers and historians with the most amplified voices. Women who look like me are the punchline, the option, the inconvenience.

We are a team. This means we actively resist the ways this world wants to prioritize him and render me small.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more