When I first heard news of the Orlando shooting last year, a family friend said something I was totally expecting: “The shooter is probably gay himself.”

If social media was anything to go by, a lot of people assumed the shooter, Omar Mateen, was queer.

When it was later discovered that he had a Grindr profile, many people – mostly cisgender, heterosexual people, in my experience – said “I told you so.”

Why were people so certain Mateen was queer?

I guess it’s the same reason why liberal media often uses homoerotic Trump/Putin imagery, especially since Trump’s election. Often, we have the idea that the people who are most bigoted towards queer people are actually queer themselves.

It doesn’t stop with Mateen, Trump, or Putin.

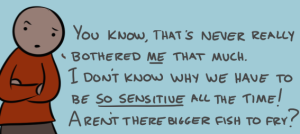

When politicians or celebrities make heterosexist remarks, a lot of well-meaning folks – especially straight “allies” – speculate whether the bigoted person is, in fact, queer. It’s a fairly popular idea that’s permeated pop culture.

And although it’s true in some cases (yeah, internalized heterosexism is a thing), we really need to challenge this trope – because it’s really violent.

Here’s why.

1. Queerness Isn’t a Punchline

Last year, a mural depicting Donald Trump kissing Vladimir Putin went viral.

At the time, many of my Facebook friends shared the image. Most of the time, they were pointing out how funny it is.

It made me wonder why it’s funny.

Why is it funny to contrast two notoriously heterosexist, bigoted men with a homoerotic image? What’s the joke? Is the joke that they’re queer?

Really?

It’s 2017, and we still think it’s acceptable to turn queerness into a punchline?

When we use queerness as an insult against politicians we don’t support, we’re implying that being queer is something to be ashamed of.

Using queerness as a pejorative implies that being queer is inferior to being straight.

So when we insult Trump or Putin by implying that they’re queer, we’re actually insulting the queer community – a group of people they both actively harm.

As a queer person, I want to see men kissing men, women having relationships, non-binary people sharing their lives together. I want to see asexual and aromantic folks, and I want to see examples of queerplatonic relationships.

I want to see queer people, both in relationships and not. I want to see people exploring their sexual and romantic orientations.

That representation means the world to me.

I want queerness represented, but not as a joke – and certainly not projected onto two people who are indescribably violent and harmful towards my community.

After all, my identity is not a punchline.

2. It’s a Distraction

Why was a mural of Trump and Putin kissing more scandalous than their heterosexist policies?

I thought it was interesting how many white, cisgender, middle-class, straight “allies” laughed about the mural on Facebook and Twitter, but didn’t share anything about how Trump’s administration affects marginalized groups of people – including queer folks, trans people, immigrants, people of color, poor people, and more.

Instead of speculating about Trump’s sexuality, let’s choose to discuss his policies and organize in whatever way we can to challenge his administration.

Let’s not distract ourselves with discussions over whether Trump is queer or not – instead, let’s do things that are actually useful and actually beneficial to queer people and other marginalized groups.

3. Equating Violence with Queerness Is Messed Up

When people see me, they assume I’m a woman.

If I tell a stranger I’m married, they’ll probably assume I have a husband – that I’m married to a man. I had to “come out” as queer, but my straight siblings never had to “come out” as straight. When I was in public with my ex-girlfriend, people would assume we were sisters or friends, not girlfriends.

My point is that we live in a world where heterosexuality is assumed. Because heterosexuality is seen as “normal,” you’re assumed to be heterosexual unless otherwise indicated.

So why did everyone assume Omar Mateen was queer – even before news about his Grindr profile came out? Why do we assume that someone is queer based only on their violence towards queer people?

When we hop to the conclusion that someone must be queer once we hear they were violent, we’re assuming that queer people are violent.

Queer people are often stereotyped as deviant, so stereotyping us as violent is dangerous.

In actual fact, we’re likely to be on the receiving end of violence, including sexual assault and hate crimes.

4. Straight People Don’t Get to Evade Responsibility

When we imply that the most queer-antagonistic people are almost always queer themselves, we imply that heterosexual people couldn’t possibly be bigoted towards us.

Naturally, this isn’t true.

Heterosexual people harm queer people all the time. But more broadly, queer people are oppressed by a system of heterosexism – a system that benefits straight people and gives them privilege at our expense.

Straight people who are acting in solidarity with us need to own up to the privilege they have. When another straight person acts up, our allies need to call that person out or in. What our “allies” shouldn’t do is try to create distance between themselves and bigoted people by saying, “Well, they aren’t like us. They’re probably gay.”

Instead of trying to evade responsibility, show up for us. Learn how to actively support us and show solidarity, and learn which mistakes to avoid.

5. We Need to Stop Acting Like the Closet Is Our Enemy

A crucial part of this trope is that the bigoted person is still “in the closet.”

This feeds into the bigger picture of how the queer community – and those who are in solidarity with us – alienates the closet and those in it.

Our community often focuses on the idea of “coming out.”

We act like coming out is a rite of passage. We say that closeted people “owe it” to the rest of their community to come out. We equate “coming out” with telling the truth and being closeted with lying. Coming out is expected. Staying “in” the closet is frowned upon.

The truth is coming out isn’t for everyone. In fact, you often have to be in a position of privilege to be able to come out safely. The people who are often most vulnerable and in need of support are those who don’t feel ready to come out yet.

Everyone’s experience of coming out will be different. For some of us, we may be fine. But, for others, it could actually be dangerous.

For example, many of us fear rejection from our families, friends, and communities – and some of us rely on our communities for financial and emotional support. For LGBTQIA+ youth, especially, this can be dangerous – which is why there’s an especially high incidence of homelessness among young LGBTQIA+ people.

It’s also important to remember that queer and trans people of color are particularly vulnerable to violence.

The bottom line is that coming out isn’t something everyone can do. When we equate closeted queer people with bigoted heterosexist people, we further alienate them.

After all, the closet isn’t our enemy. Heterosexism is.

***

While internalized heterosexism is definitely a thing, assuming heterosexist bigots are queer is harmful on many different levels.

For that reason, it’s important that we eradicate the trope of heterosexist people being closeted queers themselves.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Sian Ferguson is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a full-time freelance writer based in South Africa. Her work has been featured on various sites, including Ravishly, MassRoots, Matador Network, and more. She’s particularly interested in writing about queer issues, misogyny, healing after sexual trauma and rape culture. You can follow her on Twitter @sianfergs and read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32