Grayscale portrait of a person standing in a crowd.

I scrolled upon an interview while procrastinating on a busy day, and it made me pause. Aisha Mirza, a New York-based writer and mental health professional, had just articulated something that I hadn’t heard before, but that affected me on a deep level.

The video interview was with The Turmeric Project, a platform dedicated to queer South Asian healing, art, and community. In it, Mirza says, “I feel like when we get together, there’s often this heaviness to the experience […] this collective weight and awkwardness.”

What Aisha is speaking about is spending time with their South Asian friends in New York, and feeling this “Asian sadness” that is often associated with that experience for them.

What hit me the hardest from watching this interview was hearing the words “Asian” and “sadness” together in the same phrase. Probably, because I’m Asian and I’m “sad.”

I’m “sad” in the kind of way that I’m conscious about continually evading a sad boy trope in my public persona (I have definitely failed at this). And I’m also “sad” in the sense that…I’m clinically depressed.

So, for a second, hearing this phrase “Asian sadness” made me feel like my depression being linked to my Asian American and trans identities isn’t just something I made up to make myself feel special!

But, I’m one person. And I know that not all Asian Americans have depression. So, what could “Asian sadness” mean if it’s not always depression or palpable emotional heaviness? I think it can take many forms.

Like, bi-and multi-cultural stress, or “identity crisis.” Bi- or multi-cultural stress is generally the anxiety that someone experiences as a result of their living between multiple cultures.

These people might find themselves asking the questions, “who am I?” or “where do I fit in?” This can also be read as an “identity crisis,” but that sort of label seems to me to undermine the weight of the experience.

I follow Aisha’s work and I find it to be beautifully insightful to how what seem to be unattractive social practices, like cutting people off or calling them out, are actually often really healing for marginalized people.

Their work joins the conversation about mental health and microaggressions, and it does so in a pretty accessible and compassionate (aptly, mostly to POC) way.

In another piece they authored, titled “Why Are We So Anxious All the Time?” they assert that “our bodies do not exist in a vacuum.”

That means, our mental health problems aren’t necessarily a result of the defectiveness of our minds. They can frequently have external factors that produce and worsen them. Like, racism and trans-antagonism (a more honest way of saying ‘transphobic’).

They also say that the role of society is “chronically underplayed in diagnosis and discussion around mental health because it is more convenient for the powers that be.”

Damn is this true. They’re talking about what are called the social determinants of mental health.

In the U.S., this is spoken about — though not enough — in reference to the physical and mental health of Black Americans. Like, how class status and discrimination contribute to race-based differences in physical and mental health between Black and white folks.

Since I’m South Asian and prefer to speak from my own position, I want to talk about the social factors that can worsen the mental health of Asian American people.

I think it’s also important to talk about Asian American experience with mental health because many of us either are telling ourselves or hearing from other people that are struggles are insignificant. And that’s really not healthy.

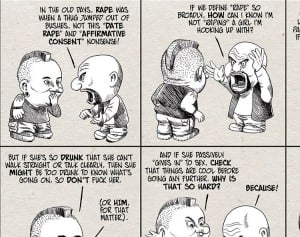

So let’s talk about one of the big contributors to Asian Americans’ cultural stress: Microaggressions.

What are some microaggressions that we Asian Americans face that might cause us to experience mental (as well as spiritual, and physical) health challenges?

I’ve compiled a list of microaggressions that make us feel more “othered” and aware of our distance from cultural belonging.

These slights can drive us to experience bi- or multi-cultural stress or what is often referred to by Asian Americans writing or speaking about their experiences as identity crises (search “Asian American identity crisis” into your search bar and check out the number of results. It’s wild).

Here they are:

1. Non-Asians acting as if they are more familiar with our “native” culture(s) than we are as Asian Americans.

I am frequently asked questions like, “do you know how to make curry? Can you teach me?” and “are you familiar with the origins of yoga practice?”

I’m clearly “brown,” and people read me as Indian. And so, of course, I also always get that mildly irritating (depending on who’s asking it) question of “where are you really from?”

People have diverse responses to expectations that they are an automatic authority on some culture that others associate with them, often based just on their physical appearance.

These questions don’t necessarily bother me in the sense that they assume that I’m un-American. Asian Americans are, after all, immigrants to a colonized land, and so should be more reflective of how our claims to belonging and American-ness can normalize colonization and invisibilize Native displacement.

But they bother me because they heighten my sense of cultural dysphoria, or, feeling like I don’t belong to any culture because I represent an ugly, rejected mixture of both.

2. Being told that we’re not really Asian because we grew up in or were born in the U.S.

We don’t only experience cultural rejection from white people, but from other Asians as well.

Often, Asian Americans speak about going back to our “native” land(s) — usually meaning one or multiple countries or regions in which our ancestors lived and had descendants — and feeling like total outsiders. This might be because we can’t culturally relate, or we have trouble speaking the native language.

Because many of us are also considered outsiders in the U.S., we may expect to automatically feel accepted in [insert country or region here] when we travel or meet people from there. The sense of: finally — my people!

But, turns out, we might even be outsiders to who we think are “our people.”

We can be told in many ways that we’re not properly Asian. In my culture (I find it humorous to say this because I have none), people like me are called ABCDs (“American Born Confused Desis”) and coconuts (brown on the outside, white on the inside).

All of these labels, while admittedly sometimes funny, emphasize our outsider status, and thus our distance from genuine cultural belonging.

As a result, we can grow more, as I name it in an earlier article, culturally dysphoric. Indian scholar, Homi Bhabha, refers to this experience as being “unhomed.”

Basically, we get mad stressed and unsure about where we fit into different cultures because the reality is that we’ve grown up with multiple — we’re complex!

3. Experiencing rejection or exoticization from non-Asian people

I was reading through an old Skype chat that I had with my white girlfriend when I was 15 years old. At first, I was really moved by the amount of care we were expressing to one another. But then I came upon a list of “100 things I love about you” she wrote about me.

Sounds cute, right? Not so much. One of the one hundred things was, “you’re my Princess Jasmine,” and another one was “you’re a hot Indian.” YIKES. She was definitely exoticizing me as a lot of my white partners have in the past.

Anyway, many people of color have a complicated relationship with feeling desired, for a number of reasons. Whether it’s our labor, our citizenship, or our attractiveness, the way that we are desired often feels fleeting and sometimes even exploitative.

An example of this for (especially femme) people who are Asian American is the perception that we are exotic, fetish objects — basically, that we are attractive based on eroticized racial or cultural stereotypes projected onto us.

Exoticization isn’t genuine attraction. It means we’re deemed both attractive, and disposable.

We’re again cast as outsiders — or, “other” — rather than being accepted into a mutually respectful space that doesn’t slap racial and cultural assumptions onto us before considering the many other aspects of our personhood.

***

While it’s important to talk about the anxieties that can arise from feeling distant from our “native” culture(s), we also need to keep in mind that we can’t responsibly claim to be insiders to a place where we have not lived or spent much time.

If we do, as Janani writes in “I’m the ‘Safe Kind of Brown,” we could perpetuate stereotypes about life in our “native” regions, because those stereotypes may actually be what we’re most familiar with as people in the diaspora.

Instead, we need to have more conversations about what it looks like for us to be embracing our hybrid identities — straddling the borders between multiple cultures and regions.

But, embracing this reality is hard work. And, unfortunately, the vast majority of Asian Americans who write and speak about this issue overlook that it’s even more difficult for people with multiple marginalized identities (like, being trans or queer) to do this. Because we’re often rejected from multiple cultures on the basis of our queer and trans identities.

And, contrary to what this video discussing Asian identity crises suggests, we can’t simply “forget” about what people think about us in order to accept ourselves.

That sort of practice of just forgetting about it seems like it requires us to suppress our emotions, and neglect our health. It reads as a privilege that isn’t as simple as it’s depicted — especially for people who are multiply marginalized, and who are anti-racists resisting assimilation into whiteness.

There is an urgency for greater attention to mental health care for Asian Americans based on these and other social factors. They cause us to not only develop identity crises, but also further feelings of alienation, confusion, and loneliness.

Mental health care doesn’t have to just look like therapy sessions.

It can be strong digital communities for people across Asian diasporas, or physical spaces for community healing. It can also look like increased media representation that depicts conflicts like ours.

Many Asian Americans hold privilege, but we also deserve to heal from our pain as marginalized people. I don’t think these two things need to exist apart from one another.

There is an abundance of healing potential in recognizing our potential harms done as privileged people, and unlearning the destructive mentalities that we have accepted for ourselves out of a need for survival.

Mirza puts this well. They say that our sadness holds the legacies of our trauma. And, if it goes unexplored, because we “become so wrapped up” in sorrow resulting from our oppression, we can neglect to be critical of our privileges and the ways we can do harm.

So, let’s talk about our sadness, and legitimize our trauma from the microaggressions that have worn on us over time. For diasporic, bi- and multi-cultural people, let’s try to embrace our hybrid identities in whatever ways we can, because always striving to fit is really exhausting.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Ayesha Sharma is a non-binary South Asian scholar and artist continually negotiating a relationship with themselves and their communities through practices of decolonization. They are most interested in literal and symbolic reclamation as an art practice and investing themselves in community care. Ayesha has written for the Urban Democracy Lab and is published in ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more