Source: Louisiana Justice Institute

“White silence is violence. White allies, speak up!”

It was not until I was thirteen, when my mother and I packed up and left the Midwest for the Bay Area, that I was introduced to the terms “white privilege” and “allyship.”

Though I was very familiar with racism at the time, through both personal encounters and my family history, I understood it to be a problem that people of color were impacted by and that people of color were expected to solve.

The notion of white anti-racism was new to me. I was deeply surprised to know that there were white people who could hold a stance other than being the perpetrators of oppression.

Both my mom and her white partner at the time, who was and is deeply entrenched in the work of anti-racism and social justice education, gave me a new vocabulary and perspective.

Back then, I looked to my “second mom” as a paragon for white allyship and moral causes, and learned much from her.

I read her book on white privilege, attended her conference sessions where she openly called out other white people on their problematic language, and engaged in dialogue on race and oppression over the dinner table.

And I watched her humbly accept accountability and apologize for the many moments her white privilege showed up.

However, while this relationship framed my expectations of other white people and self-appointed allies, it also set me up for frustration and disappointment when I went on to attend an overwhelmingly white, upper-class university.

During my studies, I met plenty of white folks who had no desire to understand my experiences as a Black student.

Instead, they spent their energy insisting that they “did not see color” – a position they might not have been in if they had a more honest education about the state of privilege and oppression in this country.

Simultaneously, I met several people who listened and appeared genuinely interested in working toward white allyship.

I met white professors who talked about racism and white privilege to their mostly white students; familiarized myself with Tim Wise (prior to his recent racist Facebook meltdown) and other white antiracists; and built close, lasting friendships and some intimate relationships with white folks committed to the cause of eradicating racism.

And, as if by guarantee, I was hurt, disappointed, betrayed, and silenced by almost all of them – even “the paragon” herself, my “second mom.”

I have often minimized this hurt by understanding that fucking up is part of the process in any and all anti-oppression work – for example, as a person with able-bodied privilege, I display unconscious ableist language and assumptions too often.

And I am also validated in my hurt and anger, in my distrust and exasperation.

I, along with so many others, am tired and brokenhearted at the sight of so many headlines announcing murder after murder after murder of Black people and indictment after indictment after indictment of the white police officers that kill us.

Still, overtime, my patience for white folks fucking up has grown long because I also know how crucial white voices are in efforts to dismantle racism.

I have come to understand that progress is not possible without activism from us all, but especially without those voices that carry the most power and influence in society.

Theory to Practice? Why Knowledge Is Not Enough

Because of the void in my K-12 and formal education, I did not truly begin academically learning about non-white, Black, queer, women, and trans* history until my first women’s and gender studies courses in college.

I became greedy in digesting this knowledge – it gave me a sense of bravery and an outspoken stance to call out oppressive shit as I saw it.

But despite my growing awareness, I still had much to learn about my own privilege, and that work is ongoing.

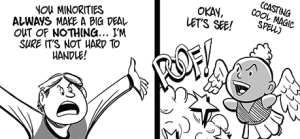

In a similar vein, I meet plenty of “white antiracists” who can school me on the latest academic terms about racism and white privilege, and I generally see these conversations as learning and movement-building opportunities.

However, these folks are also the ones whose dynamics often go unchecked – they are unable to see their own privileged behavior as a manifestation of systemic racism because they are “doing the work.”

They read White Like Me, attend the local anti-racism conferences, and they’ve got the social justice lingo down.

And while all of these actions are good starting points and appreciated efforts, they alone are not enough.

What I need white folks who are committed to anti-racism to “get” is that these conversations go beyond theory for folks of color – they are about the daily experience of racism and oppression.

I need folks to set aside what they think they know (and what they don’t), and understand the very human issue of racism.

Our pain goes well beyond the latest news conference or report on police brutality – it is deep-seated, historical, and ancestral. This is not about a single issue for people of color, nor should it be for white folks who are genuinely committed to anti-racism.

I don’t need to know about the latest definition of allyship right from the text; I need to see my allies taking risks and living what they’ve learned.

White folks who are committed to anti-racism must consider: What am I willing to sacrifice in the struggle against racism and other forms of oppression?

Relationships Across Difference

If you are a white person who recognizes your own privilege and that the ways in which people of color are treated are fucked up, it’s important for you to build relationships across race and understand how power shows up in those relationships.

Who are your closest friends, sweeties, partners, and chosen family? All white? a variety of races, ethnicities, and nationalities? What are your relationships with them like? Have you been to their houses, met their families, and listened to their experiences? Do you call your white friends and family out on their racism?

How have you supported your Black friends and partners in the wake of these intense and heightened emotions?

Personally, part of what pained me even worse about the Ferguson non-indictment was the relative silence and inaction from white and non-Black friends. They asked me how I was, but not in relation to the open season on Black and Brown folks.

The complacency of my white friends and acquaintances – who grieved the tragic death of Cory Monteith but said nothing about the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin – deeply troubles me.

These, by the way, are all folks who have read A People’s History of the United States.

I’m also hesitant of white people who say they’re allies, yet have no visible relationships with people of color.

I am equally exhausted by white folks who surround themselves with people of color and appear more “down with the cause” of anti-racism, but unconsciously perpetuate their own privilege and internalized dominance within those relationships.

For white folks, building genuine relationships and allyship across race should mean willingness to make yourself uncomfortable, consider how your actions and words may be perceived differently to a person of color, accepting accountability for inevitable fuck-ups that come along with the invisibility of privilege, and apologizing often.

It’s complicated and messy, but examining oppressive dynamics within our own inner circles is just as important as is taking to the streets in solidarity.

White Anti-Racism in the Movement: Helping or Harming?

In the midst of non-indictment and police brutality protest across the US, white and non-Black allyship has been strong.

In one such instance on December 15, 2014, white allies joined the Blackout Collective and #Asians4BlackLives in successful efforts to blockade and shut down the Oakland Police Department for four-and-a-half hours.

This, I thought, was solidarity – folks realizing that we all can do something to decry the violence against Black people and people of color in this country.

And yet, this is only one example of solidarity in the face of many disappointments.

I have been at several POC-centered events and rallies in which white voices have taken over, in which attention was deflected from the issue at hand, in which “allies” ignored requests to step back and leave the space for people of color only.

White folks have co-opted Black language and even engaged in non-peaceful protest against the wishes of POC organizers (and it is communities of color that most often take the blame for so-called vandalism and riot destruction). And that is not solidarity – not any kind I want to witness.

While the place of white allies is one that is deeply needed and appreciated, some actions (well-intentioned as they may be) produce more damage than progress.

The often unconscious action, for instance, of a white person speaking over a person of color perpetuates dominance and silences the folks directly impacted by – in this instance – police brutality and state violence. Back up.

Anger and outrage is an important and necessary tool to action, but we must consider – who has the right and reason to be angry in this space? In your privilege, your anger as a white person will also not be criminalized or seen as a threat. Back up.

As a white ally, it is good that you are engaged, it is good that you are outraged and showing solidarity. But keep in mind the space that you occupy when expressing support. Silence, complacency, and misdirected anger from so-called “white allies” only salts open wounds on the backs of folks of color.

Anti-Racism Needs to Be a Lifestyle Commitment

There is not just one way to show solidarity with people of color movements as a white anti-racist. The work must be deeply personal, beginning with examining how white privilege operates in one’s life, actions, relationships, and stances on issues of oppression.

As with any form of oppression, the work of dismantling racism and white privilege is long, tiring, and all-encompassing. White anti-racism is not a trend; it is not something to try on like a garment and take off if you don’t like the fit.

Of course, we must pick and choose our battles to conserve our energy, but anti-oppression is a lifelong struggle, and POC are fighting for the right to live.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

MJ is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. They are an awkward, Black, non-binary queer educator, activist, and musician writing to you from Oakland, CA. They’re hella into building spaces for queer and trans* youth of color, practicing kindness, using education as a tool of liberation, and making the personal political. They earned their BA in Sociology from Sonoma State University, where they served as president of the Queer Straight Alliance and advocated for students of color. They went on to earn an MA in Student Development Administration from Seattle University and remain committed to improving access and retention to higher education. Listen to their music or read more of their work. Follow them on Twitter @JustSayMJ and read their Everyday Feminism articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more