On Saturday January 19th, 2013, Black LGBT folk in Los Angeles gathered together under the banner “1000 Black LGBT March for Martin Luther King Junior.” This was my third year documenting the march and the presence of a visible Black LGBT and allies cohort within the Kingdom Day parade in South Los Angeles.

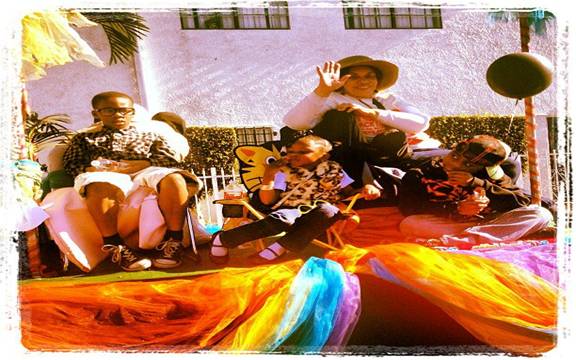

This was the first year that we had a float where our Black LGBT icons, like Jewel Thais Williams, Sir Lady Java, C. Jerome Woods, and Sandra Tignor rode through the city.

On this day our often unrecognized local Black queer historical figures were honored and literally lifted up on a pedestal for all to admire. This public display was also about showing the larger mostly Black and Brown community of South Los Angeles how our community Black and queer includes generations of folk and families of all kinds.

I’m a record keeper. I document the lives and stories of Black LGBT folk in Los Angeles. Part of doing this work means I get to enjoy the beauty of my people, out, proud, and lovely.

But it’s not always rainbows and dancing in the street. What I have learned from my almost 3 years of field work in Los Angeles is that we have some serious struggles ahead of us and a lot of those are internal.

Internalized racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and misogyny are all alive and well and we must continue to battle those beasts within.

This is essential to feminism.

My identities don’t preclude me from perpetuating some of the very types of violence that may have at one time or another been cast upon my own — Black American, working class, Black woman, Black transgender man, queer—body.

We must all begin to be more self-reflective and check ourselves.

- What kind of power do you have?

- How are you using that power?

- And most importantly for those of us who come from oppressed groups we must ask ourselves, when are we using our power?

Too many times, oppressed people use whatever power they have secured to oppress another instead of using that power to challenge the hierarchal order of things. We have to ask more of ourselves and the communities we are a part of.

Instead of making space for possible coalition, we further separate, alienate, and in the long run, decrease our chances of building mass coalitional power.

An example of this problem can be gleaned from one of my experiences at the parade that day. It was during my interview with five young Black femme-presenting women, all between the ages of 18 and 22.

I wanted to know why they thought it was important for them to be present at this event. I asked them where they found safe space to exist Black lesbian, women loving women.

I walked the young women down the street from where we had been lining up so that we could conduct their interview in a more quiet location.

As we walked, we passed a barbershop with a group of Black men, some young and some who seemed to be at least twice the age of these young women, who began catcalling.

The young women responded to the calls by shouting things that would assert their own queerness to let these men know that their calls were not going to yield any love connections.

But these men didn’t care about that.

In that moment, I became angered. But more than that, I became afraid for these young out Black lesbian women.

I couldn’t help but to think about Sakia Gunn, The New Jersey 4, and all of the women, queer people, and queer people of color who have been subject to street harassment and violence.

I thought about how many of those names go unrecognized or remembered.

I asked them, “How it is they support one another? How did they protect themselves? Is the kind of attention from those men common?” I knew the answer would be yes, because I too have walked the streets as a young Black woman.

At one point, one of the young women laughingly responded, “yes and we have to worry about these dudes raping us.”

She laughed because perhaps she was uncomfortable and laughter helps us deal with difficult things.

But I think the reality of that kind of fear of street violence is something we cannot ignore.

How many times do we as queer people experience this kind of fear of being seen and policed because what we display is non-normative, those of us who visibly where our queerness in our prancing walks, our rainbow bowties, or perhaps a bumper sticker?

Being visible means that we make space so that people understand that our love, our lives are nothing to fear (or perhaps this kind of demand for change will always incite fear, but we must not allow fear, our own and other’s, to immobilize us).

But there are, of course, those who feel like we — as queers, as women, as transgender people — need to be put back into our proper place. For some, this means no space at all.

So as we make room for our future generations and ourselves, we must also protect our lives, which are valuable even if we are devalued by larger society.

After our interview, we went back to line up with the rest of the marchers. There was a young Latino woman who walked by and I was surprised when I saw these same young women catcalling her the same way that they had just been harassed.

There was an older Black gay man, organizer, who noticed this and laughed and smiled as if to say, “oh how cute!”

But it isn’t cute.

We — as oppressed people — have to check ourselves and the ways in which we reproduced sexist and misogynist violence within and outside of our communities.

We have to check our own privilege and power because we always have some and how we choose to use it is important.

Women can be sexist. Women can hate women.

It is essential that we have these kinds of discussions in the queer community as well as other marginalized communities. It will allow us to create stronger and healthier communities that are based in self-reflection and consciousness raising practices.

We have all been raised in a society that devalues that which is feminine, poor, queer and of color. We must be careful to create our movements and political practice with this in mind.

When we allow ourselves to have these conversations we make space to deal with difficult issues, sometimes conflicting and contradictory, but this work is necessary if we hope to create a more just world.

For example, where do masculine of center partners go if their partners—femme or otherwise—are abusive?

I was in a physically abusive relationship with femme partner and I will tell you that there wasn’t much space for me to talk about the seriousness of the situation, even with friends.

They always made me feel that because I was bigger, more masculine, I obviously had more power.

Whatever she was doing, it wasn’t that serious because she was femme, smaller than I, and really what kind of power or violence could a woman really assert?

That was the logic my friends had been working with. It was also the logic that I had been working with.

I believed that because I was more masculine presenting, I really had no right to feel fear, to feel shame.

But I felt all of those things.

So my feminism is centered in a practice of self-consciousness and awareness. This means I have to unlearn a lot of what I was taught about men, women, masculinity, and femininity.

And if we allow ourselves to be more open to the ways in which we sometimes reproduce the violences that harm our communities most, we will create a more flexible politic, a more useful politic that can account for injustice anywhere it presents itself.

After all, the personal is political. And if we don’t address it within ourselves, how can we authentically and effectively address it in our society?

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32