Source: Iowa Now

Originally published on Autostraddle and cross-posted here with their permission.

I remember explaining to Harmony, my best friend in third grade, that I was a girl:

“Harmony! We can have sleepovers now!”

“But you’re a boy!” she immediately retorted.

“Well, I’m a girl now.”

Harmony rolled her eyes and walked away, confused.

I always knew I was different from the other boys.

As a toddler, I cried when my hair was cut short. I preferred girls for friends, bright colors for clothes, and dolls for toys. When I was eight years old, I announced that I was a girl. Not only was I the first openly trans* youth in my county, I was the first openly trans* person.

I started to wear dresses and makeup to school every day. I’d pack clothing from the girl’s section in with my books to put on in the classroom when no one was looking. I knew if my parents caught me, I’d have to give them up. After weeks of making it clear I was a girl at school, my teacher gave my Mom and Dad a call.

Despite my protests, the three agreed that this would just end up a phase, and decided to send me to therapy to try and stop me from expressing my true gender. This didn’t work out exactly as they planned: instead of following the therapist’s instructions to look at myself in the mirror and say that I’m a boy, I stole my sister’s makeup and wore skirts.

My mom, a well-educated doctor, continued to research the topic of transgender children. Unfortunately, this was 2003. The only (seemingly) dependable research was from Kenneth J. Zucker, a self-proclaimed trans* “reparative” therapist. His methodologically flawed research purported that an incredibly low number of gender nonconforming children ended up transitioning.

The distorted report affirmed my parents’ hope that I would change my mind about being a girl. They showed me the study and explained to me what it meant. For years, I tried to tell myself that this was a phase and I would get to live happily as a boy when I got older.

Of course, that never happened.

This fallacious research alongside the perpetual harassing and discrimination in school left me deeply questioning myself.

My school and social life quickly deteriorated. I had a difficult time making friends. The boys didn’t like me because I was a girl, the girls didn’t like me because I was a boy, and for the few new friends that I could find, their parents refused to let me speak to them outside of school fearing I would taint their children with whatever was wrong with me.

“Heshe!” “Shemale!” “It!”

I missed classes and recess because I was scared of the name-calling and terrified of the isolation. Even the teachers encouraged the other children to tease me for my identity. I couldn’t comprehend why everybody singled me out and why no one would do anything about it.

By age 10 I became quiet and fearful. My family jokingly referred to me as the “shadow child” because of how shy I had become. I stopped wearing skirts and dresses to school, sick of the teasing, which was as fundamentally attached to the clothes as the stitching.

As much as I tried to educate the school, very few listened. I believed I was the only person in the world like this and something was wrong with me mentally, as my parents and teachers had been repeating to me.

That year, I also had to quit my gymnastics class because the teacher refused to let me participate on the girl’s team after eliminating the co-ed group. For the final show, we received trophies. The girls had trophies with a woman gymnast on the top and the boys had trophies with men. To my horror, my teacher decided to give me a male trophy, outing me to all the parents there that had looked at me as a girl.

The next two years I continued hiding and lying about myself. I was only able to live as a girl part-time.

In English, we were learning about Latin roots. The rest of the seventh grade class was only half way through the book and I was bored out of my mind. One day, a particular word that caught my eye: trans – across, beyond, through. I wondered to myself, “Could transgender be a word?”

I quickly pulled out my iPod and looked it up. I thought I was being creative but in fact, the word meant something.

I knew transitioning was possible but I didn’t know someone under the age of 40 could do it. Now I suddenly had access to thousands of incredible articles, research papers, and success stories. I smiled through the entire week, something rare at that point in my life.

I became fascinated with trans* people, wanting to someday become open about being one. The German trans* celebrity Kim Petras opened my mind to the idea of getting surgery before 18. As far as I could tell, she was the first in the world to have it done at that age. Influenced by the thought that no one would accept me completely as female until I had had surgery, I was determined to be the second.

Despite being enlightened on trans* issues, my junior high school life still wasn’t a happy period. There was a large eighth grade graduation ceremony every year and the graduating students had to wear very gendered clothes and were separated on the stage by their gender. All this was in front of a crowd of a few hundred community members. I couldn’t go through with that.

I had planned months ahead to leave an I Think I Might Be Transgender: Now What Do I Do? pamphlet on my parents’ bedside table before the ceremony. I hoped they would understand the message enough to spare me from going.

When the night of my plan finally came, I couldn’t sleep. I hoped to wake up in the morning to acceptance. Instead, they said nothing and I was too frightened to ask them about it.

The dreaded graduation ceremony finally rolled around. My heart beat with sorrow as I walked into the community center in men’s dress pants and a polo shirt.

“Eli you look so handsome! I guess you were a boy all along,” said a voice behind me. I didn’t want to turn around. Instead, I ran outside and cried.

I could hear comments from teachers and family friends about my appearance. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. I let my parents push me back inside.

On the stage, I scooted my chair back, trying to conceal myself from the audience. I just closed my eyes and hoped the whole thing would end. Only after an hour of hiding behind my classmates could I finally leave.

Some of my parents’ friends told them I should see a therapist. They didn’t realize what was really wrong.

On our way back to the car, my frustrated dad asked, “Is this about you being transgender?” I looked away, ashamed.

However at this point in my life, my parents began to accept my gender identity. My mom told me she visited a Gender Spectrum conference the year before. She learned all about trans* children and care. She was ready to get me on puberty blockers or hormones.

A few days after that discussion, I went into a Macy’s to get clothes. My mom instinctively took me to the boy’s section so I gave her a look and we both smiled. For the first time, I bought my first clothing from the girl’s section that was truly mine. I didn’t need to hide anymore: I could finally be myself.

The new school year went fast. I was noticeably happier and because of my now cheerful outlook, my community accepted me. They realized that letting me transition was the right thing to do and very few questioned it. The harassment lessened because the community I lived in now knew why I was so feminine as a boy.

The next summer I attended my first trans* conference. I met lots of incredible teens and families who had gone through similar struggles that I had faced. I realized that this was a community in which I belonged and I felt at home. After years of being alone, I could finally be myself around others like me.

A few weeks later, right after my 15th birthday, I began taking estradiol and spironolactone (female hormones and male hormone blockers). I was lucky to have started puberty late: the effects of these medications are a lot stronger before puberty takes place. I continued to change my passport and other IDs throughout the year to the correct gender.

I kept my name. I didn’t want to hide who I was. If someone asked, I would be proud to announce that I’m trans*.

Over the next year, my confidence grew and I began to get more and more involved in the trans* community. I began educating teachers about trans* issues and started working with a trans* surgeon to receive gender confirmation surgery as a minor. By that fall, in 11th grade, I started a trans*-inclusive policy at my school that would have helped me while going through my town’s education system.

It didn’t stop there. I then founded Trans Student Equality Resources with Chicago-based advocate Alex Sennello to end discrimination for all trans* students, I became a GLSEN (Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network) student media ambassador and National Advisory Council member, and I started presenting at queer conferences. I eventually underwent gender confirmation surgery and became the youngest person to go public about it in North America.

My parents went through changes of their own: my dad began speaking at trans* conferences and my mom now helps run a local PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) chapter. I am incredibly privileged and grateful to have accepting parents and access to supportive medical care.

My greatest hope is that my story can give trans* youth and their families the strength to grow and change together.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

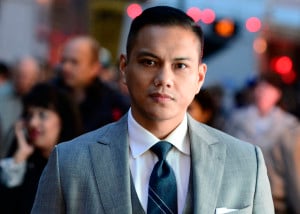

Eli Erlick is an 18 year-old trans* student from California. She is the executive director of Trans Student Equality Resources, a Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) National Advisory Council Member, and a former board member of the Coming Together to Make It Better conference and GLSEN student media ambassador. She is a Trans 100 and Refinery29 “30 Under 30″ honoree for her work in the community. You can follow Eli on Twitter at @eerlick

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more