Hey, y’all. This is another video I’m doing in a series with Everyday Feminism which is a website dedicated to helping you break down and stand up to everyday oppression, and in this video I want to talk about some questions that we women might ask ourselves due to internalized misogyny. And I’ll also suggest some alternative questions that we can ask ourselves instead, ones that empower us and affirm us.

So to start, I’m just going to give a very basic definition of internalized misogyny. Internalized misogyny, or internalized sexism, is the involuntary internalization by women of the sexist messages that are present in their societies and culture. In other words, even though we’re women, we can still hold harmful ideas about women and womanhood. So we’re socialized in a society that only values certain aspects of us, the ones that conform with traditional femininity, and we can start to internalize the messages that we’re taught about ourselves and other women. Even if we don’t recognize that we hold beliefs about women as being inferior to men, these beliefs can still affect us.

So here are some questions that I’ve asked myself as a result of internalized misogyny:

First one is, “Am I smart enough for this?” Internalized misogyny can convince us that we are inherently less smart, less capable, and less deserving of the roles and jobs that men have occupied for centuries. We’re taught to take up less space and ask less questions than boys. We’re convinced that our womanhood makes us better at certain things like caretaking, and worse at almost everything else, like math, science, sports, leadership.

I’ve often caught myself wondering, “Am I smart enough to do this? Am I capable of what I want to accomplish?” I grew up with parents supporting me, telling me I’m smart, and yet I still find myself doubting whether my years of study are enough to prepare me for the next bit of study. I catch myself thinking that someone else should take the lead in case I’m not smart enough to do something, or I stay silent in class assuming that my answer to the question is wrong.

I am smart. I know that I am. But when I open up my philosophy textbooks, it is overwhelmingly male writers. The canonical narrative of philosophy suggests that I’m the odd one out and that my gender makes me less likely to be a good or influential philosopher. This kind of subtle sexism can eat away at your self-esteem. The belief that women are inherently less smart is sexist, but it’s one that women can and do internalize despite their best efforts. It’s good to be aware that these thoughts are socialized and serve a patriarchal purpose, and that that doesn’t make them true.

So question number two is, “Am I prettier than her?” Patriarchy places us in competition with other women all the time. We’re consistently portrayed in the media as being catty and competitive for male attention, bitchy toward other women, and always striving to be the prettiest one in the room. Or the country. Or the world. The truth is, a lot of us feed into this. It’s hard not to feel in competition when so many aspects of society place us at odds with each other. We compete for men in movies and TV. We compete for the title of “Most Beautiful” in pageants. And even when we’re competing for other things, like in sports, our beauty still somehow becomes an important factor.

And being prettier than another woman can feel like a victory because so much emphasis is placed on the importance of beauty. Without mainstream beauty, women are dismissed as unimportant in our society, but we have to remember that even good looks doesn’t save us from dismissal. Traditionally, beautiful women are also up against the idea of them as therefore less smart or more vain and less useful. So basically, pitting women against one another based on something as trivial and capitalist as norms of beauty is only working against us as a whole. It works to keep women fighting each other rather than fighting against the root of our problems: a misogynist, patriarchal society.

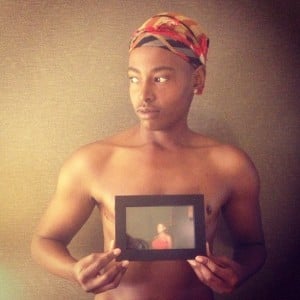

So question number three, “Am I being vain?” In our selfie-loving culture, women are often accused of being vain, for loving ourselves, or for attempting to love ourselves through self-expression; but taking a lot of selfies doesn’t mean you’re vain, and being vain doesn’t mean that you’re shallow or vapid. I think a lot of people, myself included, take selfies in order to try to love their appearance more, to find things about themselves they find beautiful, to combat what we’re told is beautiful in the media.

We also might take selfies because we’re still learning what we look like, or how we’re changing with age or puberty, et cetera, and there are many reasons to focus on one’s appearance that aren’t vain in nature.

That said, vanity is not in and of itself a bad thing, either. So I like to think of it like this: some of the greatest writers, poets, filmmakers, and other creatives of all-time were and are incredibly self-reflective. We respect people who write about themselves, make art from a personal space, write music about their lives, and generally look inward for inspiration for their craft. So why, then, is that not considered vain, but to express yourself using makeup or hair is? Why should I worry that by posting a selfie, someone will dismiss me as vain, when this thought has never crossed my mind before submitting a self-reflective paper, for instance? My outward appearance is just another expression of my inner self, so if one kind of expression is okay, then the other should be, too.

So, as women, we are simultaneously told two conflicting messages at once: one is that looks are incredibly important, and we should do and buy everything in our power to avoid aging, avoid any imperfections, and to achieve an impossible ideal in order to be successful or even just lovable; and the other message is that focusing on your looks is superficial and vain, and that there’s something wrong with that. Women are meant to be unbelievably pretty, but not meant to care about their looks too much, either.

So when we find ourselves asking, “Am I being vain? Is this superficial of me?” it’s probably because we’ve been convinced on some level that this paradox is true. So, internalizing misogynist ideas about how a woman “should” look and act affects the way we feel about our own self-expression.

So when you find yourself caught up in the internalized misogyny that almost all women have to combat in our society, try asking yourself these questions instead:

So, first one I came up with is, “What makes me a woman?” Because it isn’t my body. It isn’t my desire to dress and act a certain way. It isn’t my assignment at birth or what toys I played with when I was a child, and yet it is part of my identity. It’s the identity of many people, some of whom look like me, some of whom don’t. Some of whom stay at home with kids, others don’t want kids, or can’t have them, or have their partner stay home with them. Some who care about their appearance, and some who couldn’t care less. The point is, there’s a multitude of combinations of lifestyles and choices and bodies that make up womanhood. Remember that gender is a construct that can give meaning to our identity while still remaining a construct.

It’s meaningful to be a woman in our society. It comes with a lot of obstacles and prejudice, especially if you’re a woman whose identity intersects with other types of oppression; but as meaningful as being a woman is, there’s still so much room within it to define it for onself. There’s no right way to be a woman. There’s room enough for all types of women. It’s just up to us to make that room.

So question two, “Why should I expected to be a certain way because I’m a woman?” Short answer is, “You shouldn’t.” There’s no reason other than patriarchal bullshit that women cannot do exactly what men do. We can and do run businesses, countries, excel in math, sciences, literature, and art. We consistently break stereotypes about our gender. We continue to push back against the gender binary that confines us and men, and oppresses non-binary people. We do it all without having to sacrifice our womanhood. In fact, it’s all of these strengths which makes being a woman and knowing women so rewarding.

And my last question, ask yourself, is, “Do other women add or detract from my life?” And I mean this as a rhetorical question because honestly, women are undoubtedly a huge part of your life and add a great deal to it, whether it’s your mom, your sister, your chosen family, your online friends, your activist circle; women in your life are there for a reason. They’re not there to compete with you or make you doubt yourself, just the opposite. Other women are reminders of just how complex, varied, and indescribably powerful we can be. We are always stronger together.

I hope this was helpful, and thank you for watching. I’ll see you on my next video.