Originally published on Role Reboot and republished here with their permission.

“You have to just do what you love!”

Various forms of “do what you love” serve the purpose of being inspirational and cause people to question the meaning of life, their purpose, and search for more meaningful work.

This is especially true during critical coming-of-age moments: choosing a college, selecting a major in college, applying for jobs out of college, quarter-life crisis, mid-life crisis, retirement crisis, and so on.

And why shouldn’t we do this? Isn’t doing what you love critical to happiness?

Perhaps. In this case, however, love is also used in a way to eliminate politicizing what we do for a living. In theory, it seems quite sound. However, the context of said theory is quite problematic.

“Doing what you love” is an elitist and privileged aphorism.

The Western ideal of individualism puts us at the center of the universe and drills down. But choosing a calling isn’t necessarily about doing what we love.

Individuals in marginalized communities frequently don’t have the means to just do what they love. This includes people of color, women, the LGBTQIA+ community, and disabled people.

They may be discriminated against when trying to pursue their passions, or the resources they need might be lacking.

Those living in poverty are attempting to get through life on a day-to-day basis.

Doing what they love is a privilege they can’t even consider when they need to just get food on the table after working multiple jobs (jobs that are likely supporting individuals who are actually doing what they love).

And if they do consider it, this is short-lived. The setbacks of poverty can be quite discouraging to those who do not fit expected standards.

Women, many of whom are in the lowest paid labor jobs, may have difficulty finding adequate childcare if they’re mothers or they may not be prominently represented in the fields they are trying to enter.

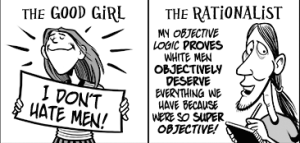

“Old boys clubs” still exist among a variety of fields, and misogyny is quite alive, even in fields where women are more represented.

The same goes for those who identify as LGBTQIA+ or disabled. When your orientation, a/gender, and/or dis/ability is already the butt of jokes and not included in many heteronormative traditions, doing what you love is secondary to your mental health.

In no way does this mean underrepresented people can’t have aspirations, be successful (whatever that may mean to the person defining success), or redefine constructs more equitably. In fact, this is precisely what needs to happen.

But in an era of inspirational memes with natural backgrounds, neutralizing the complexities of socioeconomic differences, it’s not so simple.

Even people who are privileged based on race, a/gender, orientation, and dis/ability have trouble finding their passion and pursuing it.

Even academics, who spend years engrossed in a PhD program to focus on their passion, may struggle as adjunct professors while attempting to abide by this maxim.

This isn’t an easy task, and it’s even more challenging for those who are marginalized.

As Miya Tokumitsu asserts in her essay chiding the “DWYL” mentality, marginalized folks are often doing the work we don’t love while their wages are incredibly low, their work is criticized, their stories are erased, and the gap between their work and elite work widens.

Laborers and workers, such as home health care aides or those in factory jobs, are likely not doing what they love. These vocations are low-paying, not fun, and can be demanding emotionally.

Yet, this work is necessary in society. So saying “do what you love” is inherently saying that only certain people deserve the happiness that results from it.

***

Nothing is perfect, and all jobs, no matter how beneficent, equitable, and inclusive, will still be work.

It is quite convenient for these motivational sayings to be exalted within our capitalistic world.

This is precisely why we need to identify how the constructs of race, gender, sexuality, and ability divide us rather than working within existing structures to further their intrinsic discrimination.

Perhaps then, new sayings can be promoted about the importance of justice for all of humankind.

It is on us to take a critical look at seemingly harmless sayings that motivate us, yet subsequently harm those who are marginalized.

But it is not on you, as an individual, to save the world.

This takes a collective effort.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Nisha Mody is a writer, librarian, and former speech-language pathologist raised in Chicagoland and living in Los Angeles. She is a lover of eggs, bunnies, and avocados. Her work has been published in Role Reboot, Chicago Literati, and Hack Library School. You can follow her on Twitter @nishamody.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more