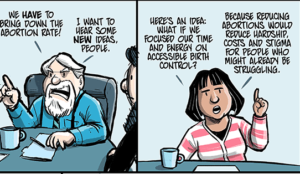

What do you think of Macklemore rapping about the benefits he and other white folks get as a result of white privilege? Is this a brave act of allyship, or a self-serving moment of white saviorhood?

What do you think of Macklemore rapping about the benefits he and other white folks get as a result of white privilege? Is this a brave act of allyship, or a self-serving moment of white saviorhood?

The hip-hop artist and his music producer Ryan Lewis just released “White Privilege II.” Some people are giving a suspicious side eye, while others say it’s a good move for white guy in a genre created by Black folks to acknowledge his privilege and get people talking about it.

If you’re a white ally, this may have you wondering what this means for you. If you have an opportunity to speak out on racism, should you take it?

Or would that mean you’re taking up space in a conversation best left to people of color?

Both sides of this debate have valid points.

If we completely discount one side or another, we also dismiss the true nature of allyship – a multi-layered, sometimes messy, always imperfect, ever-evolving process of figuring out how best to support people of color as you learn more about white supremacy and racism.

The “bad” news about “White Privilege II” is that yes, it’s imperfect. The “good” news? It makes total sense that it’s imperfect, because all allies make mistakes – so now we can talk about what Macklemore did well, and also how he can keep progressing to do better.

Here’s a chance to put yourself in Macklemore’s position. And maybe this is already familiar – you’re trying your best as an ally, but people are still telling you that you’re not getting it quite right.

That can leave you feeling frustrated, and some people give up, wondering why they should bother if their efforts are always criticized. You’re finding it impossible to judge when saying something about racism supports people of color, and when stepping into the spotlight does more harm than good.

It’s a tricky balance to find, because you don’t want to fall into white privilege inception – calling out white privilege by acting on white privilege, resulting only in your benefitting from white privilege.

Are you dizzy with the implications of white privilege yet? Welcome to my world.

You might already feel tired of being “lectured” on this topic – and okay, maybe that’s partly my fault, for using the term “white privilege” four times in one sentence just now.

But since you’re tired of hearing about how you might be contributing to racism, imagine how I, as a Black person, feel being affected by it – and stick with me a little longer for some tips on how to be an effective ally without inadvertently causing more harm than good.

Because if you’re wondering why I’d reject a genuine offer of support, you’re not hearing what I’m saying.

I’m not questioning your good intentions as a white person fighting racism. But I will point out that you’re not having a positive impact if your “anti-racism” includes collecting rewards for yourself instead of actually lifting up people of color.

There’s no definitive answer on whether you should always say something or always keep your mouth shut.

For instance, Macklemore has lots of people listening to him – which means that, depending on what he does or says, he could have a positive or a negative effect.

Throughout your life, you’ll have moments when people are willing to listen to you, too.

If you’re thoughtful about your allyship, you could give activists of color some much-needed support by taking on some of the work of educating your fellow white people – following the leadership of people of color.

If you’re not thoughtful, you could uphold society’s habit of keeping people of color out of the spotlight, giving white people credit for our ideas, and letting white folks pat themselves on the back for so-called “solidarity” without actually having a positive impact.

And guess what? Sometimes you’ll get it wrong. You’ll be silent and realize later that you should’ve said something, or you’ll speak out when it would’ve been more helpful to be quiet.

You don’t have to hold back from racial justice work out of fear of making mistakes. If you’re willing to engage with this work and learn from your mistakes, then you’re already well on your way to being an effective ally.

You’re not the only one who doesn’t have everything figured out yet – in fact, you’re in the company of literally every other ally. Take it from me: If you talk to someone who claims to be the “perfect” ally, you’re talking to someone who’s full of shit.

Macklemore is far from the only musician benefiting from white privilege, but he’s the one who’s kicked off this discussion. So let’s take a closer look at him, and at Sam Smith, Iggy Azalea, and other popular white artists influenced by Black music.

Each of their stories brings up an important question you can ask yourself, and some simple guidelines to follow. They’ll help you figure out how to be a supportive ally when the spotlight is on you – or if you should be standing in the spotlight at all.

1. ‘Is This the Best Place for Me As An Ally?’

With this latest song, Macklemore invites us into the ally questions he’s grappling with.

Should he march with Black Lives Matter? Should he be saying more about police brutality? What if he says something offensive?

You might have wrestled with some of the same questions. You can try to find some answers by figuring out the best place for you in the racial justice movement.

Macklemore’s acts of allyship are under a microscope because for the past few years, he’s been a symbol of a common problem with how the world treats music and other elements of Black culture.

Black folks can create something like hip-hop, and fight for it when the rest of the world says it’s the music of “criminals” and “thugs.” We can use it to capture our experiences, validate our struggles, and affirm our survival. We can share it with each other and find in its rhythm love for ourselves when nobody else has love for us.

And then mainstream culture can come along and swoop it up, refusing to recognize the value of hip-hop unless it’s performed by a nice white guy like Macklemore.

It’s sadly no longer a surprise to me, but even Macklemore himself was taken aback when he beat out Kendrick Lamar for a Grammy award for Best Rap Album.

So when he takes a position at the center of yet another space that should be led by people of color – talking about racism – it can feel like another case of people paying attention to him when they’ve been ignoring marginalized folks sharing the same message.

There’s no one way to be an activist. People help create change in all kinds of ways – by organizing and leading marches, donating to racial justice organizations, calling in their peers who do or say racist things, and changing their own oppressive habits, for example.

So you have many roles to choose from, and here’s a hint: The spotlight is generally not the best place for an ally to linger.

Just think about the ways that you’re oppressed – as a woman, or a poor person, or a disabled person, would you want men, or wealthy people, or able bodied people setting the agenda on what you need?

Because we directly experience racism, people of color have the most informed perspective on the kind of change we’re seeking – and we don’t always get the privilege of having our voices heard.

And that’s not because the white people who get to speak happen to be more talented or articulate than people of color. It’s part of an oppressive dynamic set by white supremacy.

We’re so often silenced in our everyday lives, then silenced again when people try to shut down our conversations on racism, and yet again if white allies take up space in the racial justice movement by putting themselves in the spotlight instead of listening to what we have to say.

On the plus side, with “White Privilege II,” Macklemore shared some of the spotlight, collaborating with artist activists of color Hollis Wong-Wear and Jamila Woods. The song also features snippets from speeches by several other activists of color.

We have yet to see if anyone but Macklemore will get mainstream attention for this, but the song could be a start. He can continue to address the music industry’s bias by paying attention to the industry’s response, and redirecting any praise focused on him to acknowledge the people of color involved in this work.

So if you get the chance to speak about racism, ask yourself: Is there a person of color who could say this instead?

Then follow these guidelines:

Pass the mic if a person of color is available to address what you’re talking about from their firsthand experience.

Ask activists of color how you can support them in getting their voices amplified. Use your opportunities to point the attention their way.

2. ‘Why Are People Listening to Me?’

So you know it’s best to step aside when a person of color could say what you want to say about racism. But sometimes it just happens that the attention’s on you.

You’re hosting an event where someone makes a racist joke, and now the microphone’s in your hand. Or you’re on your personal social media page, where it’s up to you to initiate any conversations on racism. Or people are asking for your ideas on privilege – ideas influenced by people of color.

What then? Isn’t it better to say something than nothing?

Yes, you can say something – and recognizing how your white privilege can put you in a position to do so is one way to make sure you’re saying something helpful.

Is the event you’re hosting a conference with all-white leadership? Do your friends engage with your conversations on racism, but dismiss Black Lives Matter protesters as “thugs?”

If so, white supremacy is part of the reason you have this opportunity to speak on racism.

As Macklemore’s story shows, some people are more willing to listen to white folks than to people of color – whether they’re pointing out white privilege or performing a certain style of music.

Take white soul singer Adele as another industry example. Now, I love Adele’s music. I’m not ashamed to say that, especially since the Internet made it socially acceptable to openly admit to weeping at the sound of her voice.

So for me, this is the perfect example of why I’m not hating on someone by naming their privilege – and why you don’t have to hate people of color to benefit from white privilege.

From my point of view, Adele’s just doing her thing, creating music that’s authentic to her experience, and getting some well-earned success for doing it. It’s possible to do all of this without meaning to do harm, and still benefit from the harmful industry standard of favoring white artists even in a traditionally Black genre like soul.

So she could make a big difference by using her platform to name that she’s getting a lot of mainstream attention, while deserving Black artists like Sharon Jones don’t get the same.

I’m not saying Adele has to stop making music. After all, it’s healthy to process emotions, and the woman makes me feel things, okay? My aging cat’s going to die someday, and when she does, I’m going to need a new Adele album to help get me through.

In the same way, I’m not saying you don’t deserve your success or you have to give it up by recognizing that white privilege has helped you get where you are. But people of color are often denied the opportunities that we deserve.

So if the attention’s on you and you have a chance to speak about racism, follow these guidelines:

Name what’s happening – white privilege has helped put you in this position, so you have opportunities that other people don’t have.

Don’t claim to be the first to present ideas on anti-racism, and be clear that people of color have been fighting to be heard for a long time.

3. ‘Am I Giving Credit Where It’s Due?’

Once you’ve recognized your position of privilege, you can make sure you’re not using it to exploit people of color and claim credit for what they’ve done.

Let’s go back to that white-led event where someone’s told a racist joke and you’re holding the microphone.

The opportunity for you to step up as a white ally wouldn’t exist without people of color educating allies on how they can support us.

You may wonder, does the race of someone addressing racism really matter? Isn’t it all for the greater good?

Well, let’s see – is it any different when white artists and Black artists play the same genre of music?

Here’s an example: white soul singer Joss Stone recently released her first reggae album. And what happened next is a classic story of white folks trying on traditionally Black styles – she outsold every other reggae artist and was named Billboard’s 2015 Reggae Artist of the Year.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with a white person feeling connected to reggae. But here’s what’s missing.

Bob Marley was in second place on the reggae charts – and of course, there’s no arguing with the fact that he’s hugely popular. But when a genre like reggae becomes more about popularity among mainstream white audiences, its meaning gets watered down.

In the case of Black Jamaican Bob Marley, white folks love to have his face on posters, sport his country’s flag on beanies, and listen to Legend while smoking weed. But how many of those folks understand the revolutionary message in lines like “none but ourselves can free our minds” as they sing along?

As a Black woman with Caribbean roots, I’m going to need a minute to catch my balance after Joss Stone gets accolades for being a reggae artist. This is a woman who said that she doesn’t believe cultural appropriation is an “issue,” and that people hurt by it are just “too uptight.”

And now she’s benefiting from being a “marketable” white artist at the top of the reggae genre. In this sense, “marketable” means she’s not othered by the dominating force of white supremacy like people of color are – seeing as no Black reggae artist since Bob Marley has even come close to that kind of mainstream visibility.

So what guidelines can we take from the curious case of “reggae artist” Joss Stone?

If you get a chance to call out racism like an insensitive joke, you can also acknowledge that you’re delivering secondhand information you’ve learned about why such jokes are harmful.

Say that you don’t find that joke funny, and suggest that everyone check out Franchesca Ramsey’s work. She has lots of videos that explain why casual racism is harmful, including a great one on racist jokes.

4. ‘Am I Focusing on My Own Feelings Over the Struggles of People of Color?’

Have you ever witnessed or participated in an act of racism that left you stunned at the impact?

Maybe you were with a friend who was racially profiled. Or someone helped you realize that you were profiling people based on your own unconscious biases.

Many white people share these experiences to vouch for the fact that racism does, in fact, exist.

Just don’t hold your breath waiting for people of color to express surprise at your discovery. We’ve been aware of racism’s existence for a long time.

There’s one important thing to keep in mind here. While you may have troubled feelings about what you witnessed, people of color’s struggles aren’t about you.

If you center these conversations around your guilt and devastation about racism, you’re not actually bringing attention to people of color’s experiences. You’re reinforcing the idea that your feelings are more important than our pain.

British soul singer Sam Smith could’ve been a stronger ally when he tweeted about a recent London encounter with racism. Apparently, he was with a friend who was the target of racial slurs. No word on how the friend is holding up, but as for Sam’s response?

“I never ever ever ever thought that would happen here,” he said. “Absolutely speechless and hurt. I feel like I have to shine some sort of light on it. The police were so unhelpful in the situation and its deeply shocked me.”

Everyone has to learn about racism at some point, and if you’ve had the shield of white privilege, it might take a while. So I understand that a moment like this can really change your perspective.

But it can be pretty insulting when white people share newfound shock over the existence of racism, as if to say, “Wow, people of color were telling the truth all this time! Who woulda thought?”

What’s really off here is that soul singer Sam Smith, winner of a Best New Artist BET Award, can be wildly popular in a traditionally Black genre without being aware of the basic fact that racism can happen in a place like London.

As a musician, he’s demonstrating how it’s possible for white folks to benefit from the work of people of color without actually paying attention to our lives.

And as white person disturbed by racism, Sam Smith is showing how you can make the mistake of centering your feelings instead of people of color.

This is doubly insulting – especially considering that people of color are often told that we’re being “oversensitive” when we share our own feelings about being targets of racism.

Sure, it’s helpful to shine a light on racism once you understand the gravity of it.

And with these guidelines, you can avoid making it all about you:

Prioritize the ultimate goal for making others aware of marginalized people’s experiences.

The aim is to build a world where people of color don’t have to have those experiences anymore – not just to have a platform for your tears.

5. ‘Is My Allyship About This One-Time Opportunity or Is It An Ongoing Process?’

When you’re getting attention for your solidarity, it’s important to remember that true allyship is a continuous process, not a one-time event.

Ask yourself which category your ally action falls under, and check in with this follow-up question: Does your allyship come with conditions that oppress people of color?

For instance, you might say that you support ending police violence against Black people. So will you still support us when we say “Black Lives Matter,” and not “All Lives Matter?”

What about when we express our anger about having to live in fear of police? And when we disrupt people’s lives to demand change when those in power refuse to hear us?

Will you stick with us when we point out how you contribute to the system of white supremacy that allows us to be attacked without justice?

In “White Privilege II,” Macklemore names three of the music industry’s biggest beneficiaries of white privilege – Miley Cyrus, Iggy Azalea, and himself. He owns up to the fact that all three of them get success using styles and language Black folks are routinely marginalized for.

Miley and Iggy have both rejected responsibility for perpetuating racism by participating in cultural appropriation. Miley even tone policed Nicki Minaj, saying Nicki should be “kinder” with her words on the impact of the music industry’s racism.

People of color deserve to be angry about injustice against us, and if your so-called “support” requires us to be silent about our pain, we just don’t need it. It’s far more harmful than helpful to insist that our fight against racism centers your comfort.

Taking one moment to claim solidarity from within your comfort zone doesn’t mean your work is done.

Here are some guidelines to take from Miley and Iggy’s examples of what not to do:

To really help build justice, you have to commit to the ongoing process. Don’t just look for chances to speak – also learn to listen, to apologize when you’ve made mistakes, to step back and take action to do better.

This is the hard – but necessary – work of being an ally.

***

Do you think Macklemore asked himself these questions before he recorded “White Privilege II”?

I can’t say. But I know he’s getting more attention for this song than most activists of color working to spread the same anti-racist message every day, such as these 17 unsung heroes of Black Lives Matter as highlighted by The Root.

Only time can tell us for certain if this move will have the positive impact of shifting more support to people of color, and hopefully Macklemore stays vigilant to help that happen.

If you find yourself in a similar position, then you have a lot of options for helping amplify voices of color, committing to anti-racism as a lifestyle, and following the leadership of people of color fighting oppressive conditions every day of our lives.

Keep looking out for ways you can share your power with marginalized people to make a positive difference – even (and especially) if it means you’re not the one in the spotlight.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Maisha Z. Johnson is the Digital Content Associate and Staff Writer of Everyday Feminism. You can find her writing at the intersections and shamelessly indulging in her obsession with pop culture around the web. Maisha’s past work includes Community United Against Violence (CUAV), the nation’s oldest LGBTQ anti-violence organization, and Fired Up!, a program of California Coalition for Women Prisoners. Through her own project, Inkblot Arts, Maisha taps into the creative arts and digital media to amplify the voices of those often silenced. Like her on Facebook or follow her on Twitter @mzjwords.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more